Chapter 3: Language acquisition

Language and speakers

Chapter Preview

Who is a native speaker?

Who is a multilingual?

Are there universal stages of language development?

What are language loss and language death, and why do they happen?

3.1 Introduction

We started this book attempting to define what we mean by language. We highlighted two notions of language, language as a universal human faculty (captured in the French word langage) and language as a social phenomenon comprising the range of languages spoken by human beings around the globe (corresponding to the French word langue). Having discussed issues pertaining to different languages, language structure, meaning and use, we conclude our exploration of the nature of language by considering the users of language, and the seemingly trivial issue of what to call them. In the process, we address the issue of linguistic taboo in an area where it might be least expected: the language of language itself.

3.2 The natives

To be considered a native of a country, all you need is to be born in that country. The question here is: what does it take to be considered a native speaker of a language? The problem with the definition of the compound word native speaker lies in its modifier: how exactly does the stem native modify the head speaker? Judging by the flurry of literature addressing the definition of native speaker, there is no simple answer to this puzzle.

Take one example. Due to perceived racist connotations of the term Indian, North-American Indians are currently called Native Americans, a label that appears to suggest that people of non-Indian ethnicity who are born in the United States are not native Americans. In its current use, upper-cased Native American is in fact a hyponym of the superordinate term American, which includes both native-born Americans (only some of whom are Native Americans) as well as naturalised citizens.

In some cases, the definition of native speaker appears straightforward: a Briton who is born and bred in Britain, and is a monolingual speaker of English, is a native speaker of English. But what are we to make of the following situation? Born in France to monolingual French parents, Mathilde lived in France until the age of seven, then settled with her parents in a monolingual English-speaking country, where she attends school in English and has no contact with French except through her parents. Based on her interaction with her peers and teachers at school and in the playground, Mathilde acquires a mastery of English that is indistinguishable from that of her “native” schoolmates. Her French in turn is restricted to interaction with her parents.

Is Mathilde still a native speaker of French, even though her command of the language may not be native-like? Is Mathilde now a native speaker of English, since her command of the language is native-like? The answer to these questions holds a clue to the definition of native speaker. This can be summed up in the adage, once a native speaker, always a native speaker. In other words, being a native speaker has more to do with birth-right than linguistic proficiency. You are either a native speaker or you are not. You can neither become a native speaker, nor stop being one, as evidenced by the strangeness of formulations like I became a native speaker of English at the age of seven or I stopped being a native speaker of French in my teens.

To return to Mathilde’s situation, we could describe her as a native speaker of French and a multilingual speaker of English. We use the term multilingual to designate users of more than one language, thus including bilinguals, trilinguals, and so on. But this label does not entirely capture her native(-like) command of English. This is especially so given the fact that the labels bilingual/multilingual are often used synonymously with semilingual, as we shall see in section 12.3 below.

3.2.1 Language acquisition

All children acquire the language(s) that are spoken in their environment, and all children acquire language in the same way and at the same pace. At all stages of typical language development, universal patterns can be found. For example, all children start by producing sequences like [gugugu], which give its name to the so-called cooing stage. Sequences like [bɑbɑbɑ], [dɑdɑdɑ], or [dididi] follow, in the babbling stage, but not sequences like *[fæfæfæ]. Child preference for sequences like [bɑbɑ] and [dɑdɑ] is what explains the prevalence, in many different languages, of words constituted by a reduplicated sequence of [+stop +labial] or [+stop +coronal], followed by an open vowel, to designate mummy and daddy. Since time immemorial, parents all over the world have been eager to assign meaning to their children’s productions, and preferably meanings that involve themselves as referents.

All children’s babbling reflects uses of pitch, as well as other core components of any human utterance, in sequences of rises vs. falls, stressed vs. unstressed syllables or high-pitched vs. low-pitched syllables. These essential components of language are in fact the first ones used by children to communicate meanings, such as feelings, demands or queries, in the absence of words.

After the babbling stage comes the one-word stage, where children’s utterances consist of single words only, all of which are lexical words. Common one-word utterances among English-speaking children include Doggy, Ball, Drink – closely followed, of course, by No!

Activity 3.1

The two-word stage then follows, signalling the beginning of syntax. Collocations in child speech are as significant as in adult speech: child utterances like Dolly give and Give dolly mean different things.

As their linguistic development continues, all children go through stages where they apparently make mistakes like saying drinked and comed for drank and came. In fact, such mistakes signal the emergence of morphological rules in child speech. That is to say, mistakes such as the ones above suggest that the child has acquired the rule for regular past tense formation in English, but overgeneralises it to irregular verbs. Overgeneralisation, or overextension, is apparent in other areas like word meanings, where a word like moon can be used to designate a full moon, a waxing crescent, a banana or a lemon wedge, on the basis or perceived similarities in form shared by all these referents.

Instances of overgeneralisation in child speech in fact constitute solid evidence against the popular view that children learn language through simple imitation of adult speech: the overgeneralised child forms do not occur in adult speech and cannot therefore be imitated. Rather, what children appear to do is to filter the speech they hear around them according to patterns that they progressively uncover. Child strategies to acquire command over the system behind adult uses of language are in this sense no different from those used by a code-breaker assigned the task of cracking a code. The difference between the two tasks is that children don’t need to figure it out all by themselves. Adult and other older language users guide the child by means of motherese, the language that nurtures the development of language. Motherese (also known as child-directed speech, a euphemism that avoids the female denotation of the original word) mirrors the linguistic abilities that are perceived in the child, and progressively expands these. At the two-word stage, one example of an exchange involving motherese is shown below. The mother, who is trying to get the child to nap, pops a toy dog snugly into the child’s bed and pats it:

Mother. Shhh, the doggy is asleep!

Child. Doggy sleep?

Mother. That’s right darling, the doggy is asleep. Very tired! You want to sleep too?

Child. Baby sleep!

Mother. That’s right, baby can sleep too! Come, mummy helps.

Motherese contains many imperatives and questions, uses of language that require active involvement of the listener in the exchange. Other typical characteristics of motherese include high-pitched voice and profuse repetition.

The apparent idle play of children has a crucial role in language acquisition too. To give but one example, children who suddenly discover the thrills of playing a game like peekaboo, which demonstrates the permanence of an object or a face despite concealment, are well on their way to understanding features of language such as arbitrariness (referents are independent of their names, or different languages have different names for the same referent) and displacement (we can talk about things that are not present).

Activity 3.2

Insight into the process of language acquisition, or ontogenesis, gained through intensive research since the mid 1950s, has renewed interest into the question of phylogenesis, or the origin of language itself. The question is whether ontogenesis can be said to replicate phylogenesis, and thereby help shed light into the age-old question of how human beings came to develop language. Parallels that can be drawn between the patterns of early child speech and the most common patterns found in known languages appear promising. For example, early babble consists of repetitions of syllables of the form CV, or consonant followed by vowel, before children go on to tackle CVC, VC or other syllable shapes. Many languages have CV-shaped syllables only, and most languages that have other types of syllables have CV syllables too: a CV-syllable appears then to constitute a primeval component of words.

3.2.2 Language loss

The term language loss is usually associated with the waning or dissolution of language that concerns an individual speaker. Language loss can be caused by social factors like lack of prestige of a particular language, or language variety, due to value judgements associated with those languages, or to deliberate governmental policies. One example is the typical loss of the native language of second-generation immigrants, through pressure from peer or official environments where use of the native language is seen as refusal to conform to, or assimilate with, the mainstream or dominant culture.

Language loss can also be caused by factors such as disease or trauma. The term for language disorders stemming from brain damage caused by physical injury or disease is aphasia. In the 1940s, Roman Jakobson (1941/1968) proposed that the patterns in aphasic loss of speech sounds mirror, in reverse order, those found in the typical development of language in children. That is, the first speech sounds to be acquired are the last ones to go. For example, plosives are among the first sounds to be acquired by children, and among the last to persevere in aphasia. Jakobson’s interpretation of these observations as universal traits in language emergence and dissolution continues to raise controversy today.

Patterns in language pathology contribute insight to our understanding of human language in two chief ways. First, different modes of linguistic disruption test the robustness of the rules proposed to account for observed linguistic patterns, much like computer glitches test the robustness of a programme devised to perform a particular function. For example, if pathological conditions are found to result in the inability to use verbs, or inflected words, or [+ stop] sounds, then there is reason to believe that the word class verb, as well as the concepts of inflection and stop indeed constitute relevant theoretical constructs.

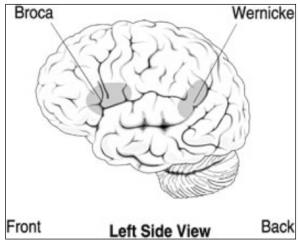

Second, disruption allows the setting up of hypotheses correlating particular types of linguistic impairment with specific locations of brain lesions. In the second half of the 19th century, two areas in the left hemisphere of the brain were found to play role in the production and in the comprehension of speech, respectively. The areas are named Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area (see Figure 3.1 below), after the researchers who first established that damage to these areas appear to result in particular types of speech impairment. Aphasics with injury to Wernicke’s area, for example, produce fluent, grammatical speech whose lexical content is nonsensical. They also have difficulty understanding speech. In contrast, individuals with Broca’s aphasia may have laboured speech, unusual word orders, and difficulties with function words such as to and if. Findings such as these suggest that grammatical and lexical processing of speech proceed along independent neural paths, and have spawned a flurry of current research into neural networks with the help of techniques such as functional neuroimaging.

Figure 3.1.

Activity 3.3

3.2.3 Language death

Whereas language loss concerns individual speakers, the term language death is reserved for the extinction of a language affecting a community of speakers. Like language loss, language death can be caused by different socio- political factors. Regulating the use of language within national boundaries continues to be an effective means of controlling ideological dissent or access to power, on the well-founded premise that a language encapsulates the culture and values of its speakers. As the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa once said, “My motherland is my language”.

Policies of linguistic subjugation (or “unification”, or “planning”, depending on one’s point of view) are what banned the use of Catalonian and Basque in General Franco’s Spain, and what lies behind debates that regularly flare up in multilingual countries like Canada and Belgium. Minority languages, or otherwise non-standard languages, are the usual targets of such policies. For example, banning the use of one minority language in schools effectively results in forcing its speakers to adopt the mainstream language, along with its culture and values. Monolingual speakers of the minority language are thereby barred from positions of power, for which official educational credentials are required. In practice, continued enforcement of such policies may result in the eradication of the targeted language from the country in question. If that language is not spoken elsewhere and, therefore, no new generation acquires it, the language effectively dies. Latin is often mentioned as the classic example of a dead language in that it is no longer transmitted across generations of speakers.

The global use of certain languages may also result in language death, this time because of suicide: speakers may voluntarily decide to stop using a language that they view as a hindrance to participation in a global community that uses another language. Linguistic globalisation therefore raises the parallel issue of language endangerment. The reason why so much attention is currently paid to the preservation, or at least recording, of endangered languages is similar to that behind efforts to preserve and map the rainforest. Endangered languages are often spoken in remote parts of the world, where they remain untouched by global linguistic trends. Just as with the rainforest, there may be something there that tells us something we need to know, in that any language may provide us with invaluable insight about the nature of language itself.

Monolingual speakers of the three current global languages, English, Mandarin and Spanish, may count themselves lucky. By the happy accidents of birthplace or upbringing, these speakers have been raised to the enviable position of users of prestige languages. They need not worry about learning another language in order to be able to partake of the global cake. And, for the time being at least, the fate of Latin, a one-time global language too, need not worry them either.

Activity 3.4

3.3 The multilinguals

As mentioned above, we use the term multilingual to refer to uses and users of more than one language, regardless of the number of languages involved in multilingualism. We do this on the assumption that there may be a difference between the use of just one language (monolingualism) and the use of more than one, but not between the use of two languages (bilingualism) and the use of more than two (multilingualism). In the literature, bilingualism is generally treated as being essentially different from monolingualism. To put it another way, the difference between monolingualism and bilingualism is seen as a difference in kind, whereas the difference between bilingualism and multilingualism is taken as a matter of degree.

One reason for this assumption may lie in the nebulous definition of multilingualism itself, and therefore of a multilingual. The term multilingual is used to label individual speakers as well as countries, individuals or groups of people that acquire several languages from birth, as well as those who learn a new language through schooling, or through settling in a different country. Clearly, each one of these is a different “multilingual”, although findings about each multilingual type tend to be generalised to multilinguals as a whole, by the use of the same word to label all users of more than one language. One added complication to the controversial definition of multilingualism is that there seems to be a reluctance to accept a multilingual as a native speaker of more than one language.

Definitions of a multilingual speaker range between extremes like ‘a multilingual knows several languages’ and ‘a multilingual is able to use several languages equally fluently in all circumstances’, both stumbling on the problem of how to quantify variables like “knowing” or “being fluent”, in order to draw comparisons. In addition, the latter definition begs the question: why would multilinguals need several languages, if they can do exactly the same thing with all of them?

We may want to start asking questions the other way around, in order to try to understand multilingualism. For example, why is a monolingual monolingual? Any monolingual will answer that they speak one language because they don’t need to speak more. The parallel with multilinguals and multilingualism then becomes clear – and perhaps not so odd, after all. People speak exactly the number of languages that they need to speak, in different settings, to different people, and for different purposes.

Activity 3.5

The fact that multilinguals have several languages at their disposal results in a sort of “buffet-effect” in their speech production, usually termed mixes. A mix concerns the occurrence of features that are ascribable to several languages in one utterance, and may involve any linguistic unit, from sounds through words to phrases. Just as a guest facing a rich gastronomic choice may want to sample the salad intended for the fish with a meat course, so multilinguals draw on the whole array of linguistic choices available to them in order to get their message through. Multilinguals do mix, but in exchanges with other multilinguals whom they know or suspect to share the same languages. In exchanges with monolinguals, multilinguals obviously recognise implicitly that mixes will result in disruption. Mixes do not, therefore, define multilinguals: they are simply the one feature of multilingual speech that arouses the curiosity of researchers, because it is not found in the speech of monolinguals.

Multilingual mixes are often discussed as evidence of poor command of language. Consequently, mixers are sometimes viewed as semilingual. One reason for assigning this special linguistic status to multilingualism lies in the fact that many linguists are monolinguals and/or subscribe to theoretical frameworks that were devised to account for monolingual uses of language. Needless to say, trying to account for multilingualism from a monolingual perspective is rather like trying to understand siblinghood on the basis of one’s experiences as an only child. Moreover, in terms of sheer number of speakers, multilinguals outnumber monolinguals, given that the majority of the world’s population makes regular use of more than one language.

The view of mixing as a deficient use of language has deep historical roots that grow back at least to Ancient Greek thought, where language impurity was equated with mixing and change (anyone whose speech was unintelligible to monolingual educated Greeks was considered a “barbarian”). Here lies perhaps another explanation behind monolingual production being treated as the linguistic norm: the one language of monolinguals is treated as a language in its pure, unadulterated state, and therefore a true reflection of the human capacity for language. In view of our discussion, in section 1.1, concerning the ambiguity of the word “language” in the current language of science, English, such mix-ups (pun intended) are perhaps unsurprising. More importantly, they are reflected in virtually all the literature on mixing, where one language is taken as the core language of an utterance, upon which the other language(s) in the mixed utterance intrude(s). In this view, one language is seen to be disrupted by the other(s). If, on the other hand, we take mixed utterances as evidence of the use of language and not of the use of several languages, we may reach a different conclusion. Speech that, from a monolingual’s perspective, is taken as mixed, may reflect instead the result of exploration of the accidental limits within which each particular language happens to vary, an exploration that is sanctioned by the open-ended nature of the language capacity itself.

An example may help clarify what we mean. The Malay word malu roughly means ‘bashful’. In Singlish, a colloquial language variety in Singapore, utterances like Very maluating and Very maluated are attested to mean, roughly, ‘very embarrassing’ and ‘very embarrassed’. Speakers of Malay may cringe at this defacing of a word in “their” language: the original malu has not only been converted from an adjective to a verb, but has also been suffixed with foreign inflections. Speakers of English may in turn cringe at the intrusion of what clearly is a foreign verb stem, whose meaning they may not understand, into “their” language. For these speakers, the Singlish utterances above are mixed, neither Malay nor English, because they fail to follow the rules of Malay and of English. But language has no nationality, and therefore no owners, and its rules need not coincide with the rules of any individual language. If inflections of a particular kind are found useful in one language, why not overgeneralise them to another language where they happen not to exist? The plural of the “English” word pizza is pizzas, with an English inflectional suffix -s, not pizze as in the original Italian. Is the plural word pizzas a mix, then? From this perspective, it may well turn out that multilinguals do not mix at all. Rather, they are putting to communicative use the open-ended resources of language that are available to them.

Activity 3.6

3.4 The others

The vagueness of the word “others” in this section is deliberate, and a form of self-inflicted linguistic taboo. All cultures have taboos, social bans restricting or prohibiting certain behaviours, which, if ignored, can result in social sanctions of various kinds.

The term itself is of Polynesian origin, and was first noted by Captain James Cook during his visit to Tonga in 1771. The Maori word tapu denotes the prohibition of an action or of the use of an object based on ritualistic distinctions between the sacred or consecrated, on the one hand, and the dangerous, unclean, and accursed, on the other. These social taboos often include linguistic taboos prohibiting the mention of certain events or entities considered either sacred (e.g. gods, religion, birth and death) or profane (certain bodily functions). Given the ban on words considered offensive in polite company, new words come to stand in for the tabooed ones, resulting in the occurrence of euphemism in all languages. Euphemistic words start off lacking the negative connotations associated with the tabooed words that they replace. But, because speakers know that euphemisms are stand-ins for tabooed expressions, over time the euphemisms themselves become negatively loaded and in need of replacement by new euphemisms.

The label “the others” is an instance of euphemism operating in the language of language. In what follows, we use it to refer to ‘non-native’ users of language. There are several reasons for avoiding the label non-native, one of them being that if there is no agreement on what a native is, then obviously there can be no agreement on what a non-native is either. The label non- native speaker generally refers to speakers who acquire a language either as a so-called second language, usually a language spoken in the country where the learner lives (for example, Malay in Singapore), or as a foreign language, where the language is not spoken in the country of the learner (for example, Japanese in Singapore). The term “second language”, confusingly, applies even to cases where that language may be the learner’s third, or fourth, and so on. Both second language and foreign language learning situations typically involve traditional methods of language teaching usually in a school setting. A distinction is sometimes made between language learning, through schooling, as mentioned above, and language acquisition, through parent- child interaction.

A second reason for avoiding the label non-native is that, as we have observed in this chapter, where matters of language description encroach upon touchy human matters of culture and national policies, scientific labels may undergo the same fate as euphemisms, becoming loaded words instead. The fact is that both the word native and its presumed opposite non-native have acquired connotations that complicate their definition in any scientifically useful way. A molecule or a prefix won’t feel affronted by being called molecule and prefix, whereas human beings can and do take offence at being called non- native. In much current research, both words are simply replaced by euphemistic acronyms, NS for ‘native speakers’ and NNS for ‘non-native speakers’, with no attempt at defining these. Alternative labels include first- language learner vs. second-language learner, or L1 user vs. L2 user, none of which have been usefully defined either.

For example, should people who speak, from birth, a language that was once imported to their country be labelled native speakers of that language? This is the situation faced by many speakers of English in India and most speakers of Portuguese in Brazil. But the language situation in these two countries is quite different. In terms of official language policy, Brazil is a “monolingual” country, because it has one official language, whereas India is not a monolingual country, because it has more than one official language.

Another example of a touchy issue concerns the current debate about whether Spanish should be recognised as an official language in the United States, given the increasing weight of the language in the country. Granting official status to a language means of course that its speakers, including monolinguals, are to be treated on equal footing with speakers of other official languages, for all purposes and in all circumstances. This is where language, ideology and power become enmeshed. There is a huge difference between labelling Spanish speakers as non-native speakers of the official language of their country and labelling them as native speakers of one of the official languages of their country. The former labels them as outsiders (the others of our section heading) whereas the latter empowers them as insiders.

Activity 3.7

In much of the literature, non-native uses of language are described as instances of multilingualism, in the way suggested in section 3.1, particularly where use of the dominant language of a country by immigrant populations is concerned. Whatever the definition of multilingualism, it clearly concerns language contact, including in its pidgin and creole forms. As was also remarked there, contact uses of language provide valuable insight into language in the making. For example, multilingual children and pidgin speakers often use the grammatical constructions of one of their languages with the lexical words of the other(s), pointing to separate neural processing of the two levels of linguistic structuring. The same separation was noted in instances of language dissolution, in section 3.2.2.

In addition, instances of multilingualism constitute strong factors of language change, in that the users, having access to more than one language, are at greater freedom to explore the creativity of language itself. Multilingual exploration may proceed through overgeneralisation of perceived rules, mirroring the common process in language acquisition mentioned in section 3.2.1. Children’s use of language constitutes another important factor of language change. Drawing on the morphological pattern of words like cooker and blender, monolingual children as well as multilinguals of all ages may produce forms like clipper for ‘scissors’ or pumper for ‘pump’, usefully compositional forms which may be “wrong” from the perspective of common uses of English but are certainly “right” from the perspective of possible uses of the language. Any word or construction that is current in a language must obviously have been introduced sometime in the history of that language in precisely this novel way, and thereafter gained use through acceptance of its usefulness by other language users.

Activity 3.8

Unexpected uses of language such as these raise the matter of intelligibility. In linguistic exchanges involving one language, the common assumption among speakers seems to be that if we speak the same language, then we do it in the same way. Recall, from section 1.1, that sender and receiver must share the ability to decode each other’s message, so that communication can take place. “One language” is thus taken to mean ‘the same code’. In actual fact, the situation is quite different. Take the case of communication in English. Its status as a global lingua franca means that most of the exchanges in English around the world take place among native speakers of other languages. A Portuguese businessman attempting a deal with a Japanese counterpart will in all likelihood speak the English that he learned in school, in a Portuguese classroom, from native speakers of Portuguese, and with the help of Portuguese glosses and paraphrases to clarify obscure uses of English. That is, he will have learnt English not as a language in itself but as some “variant” of Portuguese. The same is true of the Japanese speaker of English, both speakers being unaware that they are in fact speaking different Englishes, and that disruption may therefore arise in their uses of their “shared” language.

Here’s one example that one of the authors of this book witnessed at an international conference. An Asian participant gently reminded the Scandinavian presenter that she had exceeded her allotted twenty minutes, and asked if he could please ask some questions on her very interesting paper. The presenter checked her watch, apparently baffled by her miscalculation. Turning to the Asian gentleman, she cried “It’s not true!”, a literal translation of a Scandinavian apology rendered into English. The reaction of the Asian gentleman, and of most of the remaining audience, was to leave the room. The Scandinavian speaker had unwittingly insulted her audience by implying that they were liars. The irony is that the conference was on the topic of teaching English as a second language.

Proficiency differences between first and second/foreign languages, ranging from accent to pragmatic uses, have fed the much-debated issue of the so-called “critical period hypothesis” – the belief that the human capacity for learning language is limited to a critical age-range, variously set between early childhood and the late teens, beyond which the acquisition of a new language is either impossible or severely impaired. As evidence, researchers point to the failure of non-native speakers to reach native-like linguistic proficiency, a goal that is in itself questionable: which native variety should learners strive to emulate, and for what purposes? But the main issue is that supporters of a “critical period” fail to take into account the ways in which the new language is learnt. In traditional school settings, for example, learners are force-fed vocabulary lists and rules of “grammar” instead of being given the chance to use the language naturally in a variety of settings. Expecting these learners to achieve full linguistic proficiency is like giving aspiring bike-riders a description of the component parts and mechanics of a bicycle, and expecting them to be able to ride it. Fluent command of language arises from natural interaction among speakers, the one form of learning to which second and foreign language users generally have little or no access. In addition, keeping in mind that motivation, not age, is the prime mover of human achievement, including language acquisition, the assumption of a “critical learning period” is in fact a non-issue.

Matters of intelligibility arise not only across languages, but also within languages. Users of different language varieties might be perceived as non-native speakers by those who speak a different variety of the same language. In Chapter 2, we highlighted the twin phenomena of linguistic convergence and divergence. In linguistic convergence, speakers adapt their speech patterns at the level of word, grammar and/or intonational choices to speak more like their conversational partners, thereby narrowing the sociolinguistic differences between themselves and their partners. We can see convergence at work in the way adults accommodate their speech when addressing young children, in order to match the child’s linguistic proficiency. Similarly, when speaking to someone perceived to be of lower status than ourselves, we converge towards their speech patterns in order to reduce social distance through speech. Conversely, speakers may choose linguistic divergence to highlight the social differences between themselves and their conversational partners.

Activity 3.9

In terms of speakers of different varieties of the same language, the question that arises is: do non-natives want to speak like natives and, if so, which natives? Research into these matters reveals apparently paradoxical findings, to the effect that a British accent, say, is evaluated by non-British listeners as correlating with higher levels of intelligence, education and politeness compared to other accents of English, while the same listeners state that they would at all costs avoid the use of such an accent because they don’t want to sound “posh” or “pretentious” (recall the Lette quotation in the Food for thought section of Chapter 2). Faced with linguistic dilemmas such as these, speakers often settle for what can be usefully viewed as another form of multilingualism, where international-like and local-like varieties of the same language are used in distinct situations. Examples of these choices are the uses to which Singaporean speakers put varieties like Singapore Educated English and Singapore Colloquial English (Singlish), or the uses of Standard German and Swiss German (Schweizerdeutsch/Schwyzerdütsch) in German- speaking parts of Switzerland.

In our discussion of dialects, we highlighted that a dialect is a regional language variety which characterises a speech community, whose members choose to see themselves as speakers of the same language. In other words, whether or not some variety is a language or a dialect is as much a socio-political question as it is a linguistic one. The same comment can be made about intelligibility. Whether two speakers find themselves mutually intelligible has to do with the relationship among them. Intelligibility concerns whom we are communicating with, whether we really want them to understand us, and whether they really want to understand us. Local uses of a language, from accent through syntax to pragmatics, can effectively screen off uninitiated speakers, and therefore be used as a weapon in demarcating one’s territory, or linguistic identity. As one Hong Kong native once put it, in response to an Englishman’s baffled query about whether it was really English that people were speaking to him, “Everybody speaks English in Hong Kong, but nobody understands what you say.”

3.5 Several speakers, one language

Our investigation of human language and its users throughout this book may at first sight suggest that human beings all over the world are talking at cross- purposes from within the well-protected codes of their individual languages. A closer look, however, reveals the opposite trend. The recurrent and fruitful application of constructs like lexical word, constituent, phoneme, distribution, intonation, register, to forms and uses of language across different languages and speakers compels us to realise that we all speak the same language. This is no different from saying that I am similar to a gecko or a lion in terms of my anatomical structure in that all three of us can be usefully described by a label like vertebrate, which distinguishes us from invertebrates like jellyfish and snails.

The lexicon of linguistics, dreaded by generations of budding linguists, is no different either from the lexicon of any other language, technical or otherwise. In the same way that it is easier to use a word like cat for the complex being designated by the term cat, it is also more economical to use shorthand like suffix for ‘a bound morpheme that attaches to the right of a stem’ and homophones for ‘words that sound the same but are spelt differently’. Learning technical terminology is like learning a foreign language, at times more puzzling because the words of that language may be the same as those of familiar languages, only with new meanings. The language of language, by the very nature of its object and its users, encapsulates a culture, too, with associated taboos, ambiguities and deliberate vagueness, and with a choice of labels that, expectedly, reflects human interaction and human forms of social organisation. Natural classes, contexts and alternations mirror peer-groups, favourite hangouts and variant ways of behaving in different settings in everyday life. Similarly, linguistic heads, sisters and adjuncts behave in similar ways to the human beings in the relationships described by these labels.

Linguistics provides us with the tools that crack the code of our common language. Giving you a first glimpse into the unifying nature of the language of language has been the purpose of this book.

Food for thought

Emir (age 4): “I can speak Hebrew and English.”

Danielle (age 5): “What’s English?”

Quoted in Jill G. de Villiers and Peter A. de Villiers (1978).

Language acquisition. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

“And what should they know of English who only English know?”

Adapted from Rudyard Kipling (1891/1949). The English Flag. In Rudyard Kipling’s Verse. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Further reading

Aitchison, Jean (2001). Chapter 10. The reason why: Sociolinguistic causes of change. In Language change: Progress or decay? (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 133-152.

Gleason, Jean Berko (2005). Chapter 1. The development of language: An overview and a preview. In Jean Berko Gleason (ed.), The development of language (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon, pp. 1-38.

Kachru, Braj B. (ed.) (1992). The other tongue: English across cultures (2nd ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Obler, Loraine K. (2005). Chapter 11. Developments in the adult years. In Jean Berko Gleason (ed.), The development of language (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon, pp. 444-475.

References

Goodglass, Harold and Geschwind, Norman (1976). Language disorders. Aphasia. In Edward Carterette and Morton P. Friedman (eds.), Handbook of perception: Language and speech (vol. 7). New York: Academic Press.

Jakobson, Roman (1941/1968). Child language, aphasia, and phonological universals. The Hague: Mouton.

Attribution

This chapter has been modified and adapted from The Language of Language. A Linguistics Course for Starters under a CC BY 4.0 license. All modifications are those of Régine Pellicer and are not reflective of the original authors.