Chapter 1: Language and linguistics

Language and linguistics

Chapter Preview

On language:

What do we mean by language?

What do we mean by grammar?

What competences do language users have?

What are some of the key features of language?

On linguistics:

What characterises linguistics as a discipline?

What are the key features of scientific investigation?

What criteria do we use to evaluate linguistic analyses?

How do we acquire data for linguistic analysis?

1.1 What do we mean by language?

Have you ever wondered whether language is a capacity unique to human beings? The answer obviously depends on what we mean by the word language. If you look in a dictionary, you will find at least two characterisations of language:

- The system of human communication, using arbitrary signs (e.g. voice sounds, hand gestures or written symbols) in combination, according to established principles/rules.

- Such a system as used by a nation, people or other distinct community/social group.

The main difference between the two meanings of the word language seems to be a difference between language in theory and language in use.

The first meaning focuses on language as a universal human phenomenon, language as a mental or cognitive phenomenon, which might be paraphrased by an expression like ‘language faculty’. In contrast, the second explanation focuses on language as a social phenomenon, i.e. the language faculty as it is expressed in individual languages like Mandarin, Portuguese, Malay or English. These two notions of language – as a mental phenomenon and as a social phenomenon – are captured, in English, in the one word, language. But in French, the language in which the father of modern linguistics, Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1915/1974), conveyed his ideas about the nature of language, the two meanings of language are encapsulated in the words langage, referring to the language faculty, and langue, referring to particular languages. We detail the relationship between the two notions of language in the remaining sections of this chapter, as well as in the next chapter. But, for the moment, let us consider another way in which we might explain what is meant by the term language.

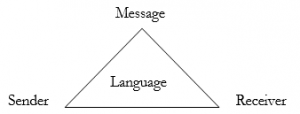

Typically, when we wish to explain what something is, we do so in terms of its form and/or function. For example, if you wanted to explain to someone what a car is, you could describe it as a four-wheeled road vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine and designed to transport passengers. This explanation focuses on both form and function: it tells us what a car is made up of, and what it is for. Similarly, in explaining what language is, we can talk about its form and its function. In terms of form, language can be thought of as a code, i.e. a set of arbitrary signs (voice sounds, hand gestures, written symbols) and the rules for combining these into specific patterns, in order to express meaning. The crucial point to note here is the rule-governed (as opposed to random) nature of codes, and therefore of language. Codes comprise definite rules for combining signs into meaningful patterns, and this is why they allow meaning to be expressed through them. To communicate by means of a code, senders and receivers must share the same set of signs and rules for combining them. Likewise, language comprises a set of signs and the rules for combining them, in order to send and receive messages, as shown in Figure 1.1 below:

Given the analogy between language and codes, you might think that the primary purpose of language is to enable communication. After all, the purpose of codes is to enable communication between senders and receivers of coded messages. But, you would only be partially right. While codes and language are certainly both means of communication, the primary purpose of language, you may be surprised to learn, is not communication but the expression of meaning, as highlighted in the quote below:

Language is a tool for expressing meaning. We think, we feel, we perceive – and we want to express our thoughts and feelings, our perceptions. Usually we want to express them because we want to share them with other people, but this is not always the case. We also need language to record our thoughts and to organise them. We write diaries, we write notes to ourselves, we make entries in our desk calendars, and so on. We also swear and exclaim – sometimes even when there is no one to hear us. The common denominator of all these different uses of language is not communication but meaning.

(Anna Wierzbicka, 1992, p. 3)

The question then becomes: how does language link meaning to expression? The answer is: through grammar, as depicted in Figure 1.2 below.

Meaning

↕

Grammar

↕

Expression

Figure 1.2. How language links meaning to expression

1.2 What do we mean by grammar?

Simply put, the grammar of a language comprises a set of signs (its sounds and words) and the principles, or rules, for combining these into meaningful utterances.

Given this concept of grammar, it follows that every human being who speaks a language knows its grammar, and it makes no sense for the speaker of any language to say I don’t know any grammar or My grammar is poor. If you can function in a given language, then you know its grammar, i.e. the code for expressing meaning in that language.

One reason you may think you don’t know the grammar of your language is that this knowledge is largely unconscious or implicit. An analogy might help to make things clearer. Think about your ability to walk or run. You know how to do it, but if someone asked you to explain what is involved in walking or running, you would probably end up with a severe case of paralysis by analysis, as would most people. Analysing what is involved in the process of walking or running is the job of the sports scientist, not the sportsperson. Similarly, all language users implicitly know the grammar of their language, and what the linguist seeks to do is to build a model of this mental grammar, i.e. of the implicit knowledge that speakers possess about the structure and use of their language.

At this point, it is worth correcting two common misconceptions about the nature of linguistics, which, we think, might be the source of misconceptions about the nature of grammar. The first is that linguistics is the study of language with the goal of learning to speak well. One of the most frequent questions linguists get asked, at parties and other social functions is: So, how many languages do you speak? or its variant How many languages do you need to speak, if you want to become a linguist? It certainly is true that some linguists are fluent in two or more languages. But the point is that a linguist is not someone who speaks several languages well. Such a person is a polyglot (from Greek poly meaning ‘many’ and glotta meaning ‘tongue’, or language). In other words, it is not necessary to speak several languages in order to be a linguist. Again, an analogy might help make things clearer. How many musical instruments do you need to play, if you wish to study music theory? The answer is none, since you can study music theory without knowing how to play any particular musical instrument. Obviously, when it comes to language, every linguist speaks at least one, by virtue of being human. But the point is that one does not need to speak any particular language, in order to do linguistics. (To find out how linguists manage to study the grammar of languages they do not speak, see sections 1.6 and 1.7.)

A second common misconception about linguistics is that it prescribes how people ought to speak, when, in fact, it describes how people actually speak. In other words, linguistics deals with what is, not what ought to be. This distinction between prescription and description is important in all disciplines, not just linguistics. Consider, for instance, the domain of ethics. If you wish to create a theory of ethics, you have two choices. You can either describe how people actually behave, in terms of the ethical choices they make. Or, you can prescribe how people ought to behave. Similarly, if you wish to create an economic theory, you can describe how people do actually behave, economically. Or, you can prescribe how you want them to behave. Most academic disciplines take the former stance, describing the world around us rather than prescribing behaviour. This is because prescriptivism tends to be based on the value system of some particular individual or group, and raises the question why that group’s value system should be the one guiding everyone else’s behaviour. This distinction between prescriptivism and description also applies to notions of grammar.

Activity 1.1

Before you read the next section, write down what you understand by the term grammar. Then, compare your understanding of this word with that of your friends, your parents, your teachers. What similarities and differences can you see among the definitions you have collected?

One reason why the notion of grammar that we outlined at the beginning of this section may have surprised you is that many people think of grammar in prescriptive terms, i.e. as a set of rules that tell people how they should speak. Linguists refer to such grammars as prescriptive grammars in order to distinguish them from the kind of grammar that linguists are interested in. Prescriptive grammars are so named because they comprise a set of prescriptions about how to speak, which are based on nothing more than the idiosyncratic value judgments of the particular individual or group prescribing the rules. The rules below are all examples of prescriptive grammar rules:

Never start a sentence with and or but.

Never end a sentence with a preposition.

Never use a double negative.

Always say I am not, never I ain’t.

If you ask the prescriber the reason for these rules, they are likely to answer that the best people (i.e. the people doing the prescribing or some group whom they wish to emulate) follow these rules, and therefore so should you. Not to speak in the fashion prescribed by them is considered bad form, and likely to be taken as a sign of the speaker’s ignorance, stupidity, lack of class, etc. Prescriptive rules seek to control behaviour by telling people what to do/what not to do. Traffic rules are a good example of prescriptive rules. In contrast, descriptive rules state the patterns or regularities observed in the behaviour of entities of various sorts. The rules governing the motion of physical objects are a good example of descriptive rules. Newton’s Laws of Motion describe how objects in motion behave under different circumstances, not how they ought to behave. Similarly, the linguist’s descriptive grammar is meant to model the principles, or rules, that speakers seem to be implicitly using, when they speak to one another.

Activity 1.2

One of these statements is prescriptive, and the other is descriptive: which is which? How did you arrive at your answer?

- Multilinguals should avoid mixing their languages when they speak.

- Mixing languages is common in multilingual speech.

To summarise, then, prescriptive grammars tell people how they ought to speak, while descriptive grammars describe how they actually speak. In building descriptive grammars, linguists do not judge linguistic utterances to be correct/incorrect. Rather, they accept language users’ intuitions about what sounds fine/odd in a given language variety, and seek to explain this asymmetry between what speakers consider acceptable/unacceptable, in the simplest and most general way possible (for more about the criteria used by linguists to evaluate alternative explanations, see section 1.6).

1.3 What competences do language users have?

In the preceding section, we emphasised that anyone who knows a language knows its grammar, i.e. the sounds and words of that language and the established conventions for combining these into meaningful utterances. In attempting to build a model of language users’ mental grammar, linguists typically talk about two kinds of competence, or two kinds of knowledge that language users possess, namely, grammatical competence and communicative competence. Grammatical competence refers to language users’ knowledge of the sounds and words of their language and how to combine these into well-formed utterances with the desired meaning. Communicative competence in turn refers to language users’ knowledge of how to use language appropriately in order to carry out specific tasks and achieve the desired effects in specific communicative situations.

‘

Here’s an example to help you see the difference between the two kinds of competence. Consider the following utterance: Can you tell me what time it is? Speakers of English would judge this a well-formed expression, in contrast to the expressions Can time it what tell you me is? Or You tell me can time is what it?, which most speakers of English would judge as being ill-formed. This is grammatical competence at work.Now consider the following exchange between individuals A and B. A doesn’t have a watch, and stops a passerby, B. A says to B, I’m sorry I don’t have my watch. Could you tell me what time it is, please? B answers Yes, and walks off. Were you surprised by B’s behaviour? If so, it’s because your communicative competence tells you two things. First, that the question Could you tell me what time it is, please?, although structurally similar to questions like Could you buy some milk on your way home? or Could you feed the dog tonight?, which require just a yes or no answer, is different in function. Second, that in asking this question, A was not asking about B’s willingness to tell her the time, but was in fact requesting B to tell her the time. In other words, A wasn’t saying Would you be willing to tell me what time it is? but Please tell me the time.

Since there may be a gap between what speakers say and what they actually intend, what is it that helps us reconstruct implicit meaning, and decide what forms are appropriate in a given communicative situation? The answer is: our communicative competence – our awareness of how situational context, including the setting, the purpose and the participants in a communicative exchange, affects the interpretation of any utterance. We discuss the importance of situational context in greater detail in Chapters 10 and 11, dealing with pragmatics, or meaning in action, and discourse, or language in use, respectively. For the moment, here’s another simple activity to reinforce the idea that every language user, including yourself, possesses both grammatical and communicative competence.

Activity 1.3

Both expressions have the same form. They both comprise two words: No followed by a plural noun – bananas and bicycles, respectively

The first expression (No bananas) may be a little harder to make sense of, but we can try to imagine a context in which you might encounter it. Suppose you saw these words on a handwritten sign at a fruit store. Would you infer the meaning ‘No bananas for sale’, on analogy with signs saying No gas at petrol stations that have run out of petrol to sell, during an oil embargo? If so, the function of this expression is declarative (telling us what is the case), rather than directive (telling us what to do), as in the case of the No bicycles sign.

Activity 1.4

What the activities above highlight are two important features of language use: the role of context in interpreting meaning, and the lack of one-to-one- correspondence between form and function – themes that we will be revisiting throughout this book.

1.4 What are some of the key features of language?

We now move on to consider five design features of language which, taken together, characterise language as a universally and uniquely human phenomenon, namely, arbitrariness, discreteness, compositionality, creativity, and rule-governedness.

1.4.1 Arbitrariness

We started this chapter with a dictionary definition of language as a system of human communication that makes use of arbitrary signs.

A sign is an indicator of something else, and signs can be divided into two kinds: arbitrary signs and non-arbitrary ones. Non-arbitrary signs have an inherent, usually causal, relationship to the things they indicate. The adage where there is smoke, there is fire is a fairly reliable observation, given that smoke- free fires tend to be a rarity. So we can say that smoke is a non-arbitrary sign of fire. Similarly, dark clouds are a non-arbitrary sign of impending rain, because there is a direct connection between the two.

Language is different from these phenomena in that the association between a linguistic form and the meaning it expresses is not inherent but established by convention. This explains why different languages have different signs representing a particular entity. Consider, for example, the animal that English speakers refer to as elephant. The linguistic sign for this entity is gajah in Malay. Why? Because these are the expressions that speakers of English and Malay have agreed (by established convention) should refer to this particular entity.

Activity 1.5

What Juliet seems to be highlighting is the arbitrary, or conventional, nature of linguistic signs. The flower that Juliet mentions happens to be called a rose because that is what speakers of English have agreed to call it, and not because there is any inherent connection between the word rose and the sweet-smelling entity that it designates. Malay speakers refer to the same entity as bunga mawar. In other words, Juliet is reminding us that the names that we give to things are not to be confused with the things themselves: linguistic signs should not be confused with the reality they represent.

There are, in fact, two levels of arbitrariness in language. The first is the arbitrary association between the form of a linguistic expression and its meaning. This level highlights the fact that there is no inherent link between the form of a word, i.e. the sounds that constitute a word, and the meaning of that word. For example, there is no inherent reason why the sequence of sounds [f], [r], [i], that gives us the word form free, should have the meanings that we associate with this word form, e.g. ‘not enslaved’ or ‘not busy’ or ‘without payment’. The same meanings could just as easily be expressed by some other sound sequence, e.g. [gip] or [gub] or [bub]. It just so happens that speakers of English have agreed to associate this particular sound- sequence [fri] with this particular set of meanings.

The second level is the arbitrary association between a linguistic sign and its referent. This level highlights the fact that there is no inherent link between a linguistic expression and the entity that it designates. For example, there is no inherent reason why the word tree should refer to the entity that it in fact refers to. There is no logical reason why the word tree could not refer to Juliet’s rose, except that speakers of English have agreed by convention to use the words rose and tree in the ways that they do.

This double arbitrariness between linguistic forms and their meanings, and linguistic signs and their referents is one of the characteristics of language, first discussed by Saussure (1915/1974) in his Cours de linguistique générale (Course in general linguistics).

1.4.2 Discreteness and compositionality

Discreteness and compositionality are two sides of the same coin. Discreteness has to do with the fact that speakers of all languages can identify distinct elements in their languages, such as the different words in a sentence, and the particular sounds in a word.

Consider the utterance Thecatsatonthemat. As a speaker of English, you have no difficulty identifying distinct elements in the sound stream making up this utterance – you hear both the individual sounds in every word and the individual words making up this utterance. This ability to distinguish discrete units in a stream of language is in fact one of the things you become aware of, as you acquire a language. You realise that you can make out individual sounds and words in the stream of language you are hearing.

While discreteness refers to our ability to perceive distinct units within larger stretches of language, compositionality refers to our perception that larger units of language are composed of smaller units. Speakers of English perceive the utterance Thecatsatonthemat as being composed of the words The, cat, sat, on, the, and mat. Similarly, they perceive each word as being composed of individual sounds, e.g. the word cat as being composed of three sounds, which we can represent by means of the symbols [k], [æ] and [t].

Putting discreteness and compositionality together, we can say that speakers perceive language as being composed of discrete units which stand in a part-whole relationship to one another. As you continue to work you way through this book, you will learn more about some of these units and their relationship to one another.

1.4.3 Creativity

Like arbitrariness, which functions on two levels, creativity in language manifests itself in two ways. First, language itself is creative in that it enables the expression of new meanings, as and when they are needed, for example through the creation of new words. As will become clearer in the next chapter, language is an organic entity, which changes, grows and dies, just like the human beings that use it. This intrinsic creativity is one of the factors underlying the phenomenon of language variation, across time, space and situations of use, which we also explore in greater detail in the next chapter.

What is interesting about the creativity of language is that it involves the “infinite use of finite means,” as highlighted by the 19th century German philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt (1836/1999: 221). All languages have a finite repertoire of sounds. Yet, from this finite set of sounds, every language is able to build a vast range of words, to serve the needs of its speakers. From this vast vocabulary or lexicon (the inventory of words in a language), in turn, an even greater number of sentences can be constructed to express every possible meaning which speakers wish to convey.

The infinite use of finite means also characterises the second way in which language is creative, namely, speaker’s use of language. Think about your own language use. When you wish to express some meaning, do you have a limited repertoire of sentences stored in memory for immediate recall? Or do you find yourself uttering novel sentences, as and when you need them? Consider, for example, the sentence below:

The little old lady who tried to carry the Golden Retriever disguised as her son into the 601 bus was told off by the commuter holding a fainting bald eagle by its left foot.

We are pretty sure that you will not have encountered this sentence before, since we just made it up ourselves. In other words, this sentence is novel both for you and us. Yet, neither of us has any trouble making sense of the sentence. What this suggests is that speakers of all languages can both understand and produce utterances that they have never before heard or spoken. The reason we are able to do this is that all languages have a limited repertoire of sounds and words, which can be combined to form an infinite number of meaningful utterances through a limited set of rules. This brings us to the fifth characteristic of language that makes it universally and uniquely human – its rule-governed nature.

1.4.4 Rule-governedness

We started this chapter by comparing language to a code. We said that codes allow the expression of meaning because they comprise a set of signs as well as rules for combining the signs into meaningful patterns. Paradoxically, it is the rule-governed nature of language that makes language use a creative enterprise. It’s easy to mistake creativity for a case of anything goes, for absence of rules. That, however, would only result in total confusion, or in the case of language, random noise. What language use involves, as any other creative endeavour, is the combination of a finite set of resources in new and different ways, in order to create new meanings.

When linguists explore the rules that govern language, they tend to focus on two kinds of organisation: linear order, or sequencing, and hierarchical order, or part-whole relationships. We talked briefly about hierarchical order when discussing compositionality as a characteristic of language, in section 1.4.2. Hierarchical order has to do with constraints in the part-whole relationships assumed by discrete units of language. Linear order in turn has to do with constraints in the sequencing of language elements. Here’s an example of linear order in terms of the sound-sequences that form words. Consider the three sounds in the English word cat, represented by the symbols [k] , [æ] and [t]. Each of these sounds has no meaning in and of itself. But each can be combined with the other two to form meaningful units at a higher level, i.e. words. What’s interesting here is that mathematically speaking, three sounds can be ordered sequentially in six ways, as shown below (in linguistics, an asterisk preceding an example indicates a non- occurring form in a particular language):

[kæt] [tæk] *[ktæ] *[tkæ] *[ætk] [ækt]

Yet, of these six sequences, only three are sanctioned by the sound- sequencing rules of English: [kæt] cat, [tæk] tack, and [ækt] act. These data reflect the intuitions of speakers of English about the possible sound- sequences of English. That is to say, if you asked speakers of English which of the six forms above represent English-sounding words, as opposed to foreign-sounding ones, their judgments would match our observation that that [kæt], [tæk] and [ækt] are fine, but not [ktæ], [tkæ] and [ætk]. In other words, the grammar of English disallows sequences like *[ktæ], *[tkæ] and *[ætk]. Once you have read Chapter 6, dealing with the sound systems of languages, you should be able to revisit these data, and articulate a rule that explains why words like *[ktæ], *[tkæ], and *[ætk] are non-occurring in English.

In discussing these and other examples about the words of any language, it’s important to keep in mind the difference between possible and actual words. For any language, there are words which could exist in it, but for some reason don’t. Possible words are words that could be part of a particular language, i.e. that are sanctioned by the grammar of the language, but just happen not to. This means that there are accidental lexical gaps (word gaps) in all languages. For instance, if you asked English speakers whether the sound sequence [fik] is a possible English word, they would answer yes. In contrast, if you asked the same set of speakers whether [bnik] is a possible English word, they would probably answer no. What [fik] and [bnik] share is that neither is an actual word of English. The difference between them is that [fik] is a possible word of English, whereas [bnik] is not. The reason is that the grammar of English allows the sound-sequence [fik] but not the sound-sequence [bnik]. Once again, you should be able to revisit these data to articulate a rule that explains why sound- sequences like [bnik] [bnæk] and [bnag] are not possible words of English.

Linear order is important for studying not just possible sound-sequences in words, but also possible word sequences in sentences. Consider, for example, the five-word sentence The cat licked the boy. Mathematically speaking, there are 120 ways to sequence five words. Most of these sequences, however, result in nonsensical strings like *Boy the licked cat the or *Licked cat boy the the. One results in a different sentence, The boy licked the cat. We will be looking more closely at the rules governing word order in sentences. Meanwhile, the sound-sequence and word-order examples above illustrate the rule-governed nature of language. All languages have rules that enable them to convey meaning. The grammar of any language is a statement of the coding rules of that language, shared by the speakers of the language. It is these rules that linguists seek to capture and model in descriptive grammars. How they go about doing this is the subject of the remaining sections of this chapter.

1.5 Linguistics: the science of language

In section 1.2, we corrected two common misconceptions about linguistics, pointing out that linguistics is the scientific study of language as a human phenomenon. In this section and the next, we explain what we mean by science, and highlight the features that characterise linguistics as the science of language.

Simply put, science is the art of looking for patterns, and for ways of explaining them. Scientists look for regularities in the world around us, and propose analyses for these regularities in the simplest, most general and most objective way possible. The characterisation of science as an art is deliberate, on our part, given the tendency to treat science and art as mutually exclusive domains. Certainly, in everyday usage, the word science is often used as a cover term for domains of study such as physics, chemistry and biology to distinguish it from areas like history, geography or literature. Science, however, refers not to an area of study but to a way of studying. In other words, any phenomenon can be the object of scientific study.

Every one of us is a scientist to the extent that we look for regularities or patterns in the world around us, and seek to explain them in terms of theories that we hold, either implicitly or explicitly. For example, if you’ve ever been puzzled by a friend’s behaviour, it’s because you have a theory about how friends in general behave, and how your friend in particular behaves, within which the quirky behaviour that you observed does not seem to fit. If you then decided to investigate the reason for your friend’s odd behaviour, in order to better understand it, you might have ended up having to amend your theory about your friend’s behaviour, in particular, and/or friends’ behaviour, in general. Observing and analysing situations, critically evaluating alternative analyses, and amending (or rejecting) an analysis on the basis of new (or conflicting) data are elements central to scientific investigation, the topic of the next section.

1.6 The nature of scientific investigation

Any investigation, including scientific investigation, can be thought of in terms of three parameters: the object of investigation, the method(s) of investigation, and the purpose of investigation. These three features correspond to three questions:

- What do you wish to study?

- How will you study it?

- Why do you wish to study it?

Being the science of language, linguistics has an object of investigation, namely, language as a universal human phenomenon. Its method is empirical. That is, the conclusions drawn in linguistics, as in any scientific investigation, are based on observation and experience rather than on intuition or pure reasoning. The purpose of linguistic analysis is to explain the nature of language, in order to be able to answer questions like What constitutes knowledge of language? How is language acquired? and How is it used? In the next three subsections, we look at the object, method, and purpose of scientific investigation a little more closely.

1.6.1 The object of investigation

Typically, scientific investigation deals with observable phenomena. In other words, science is interested in factual claims, in assertions which can be demonstrated to be true or false, based on empirical evidence. The difference between fact (something that you know to be true) and opinion is that the latter cannot be demonstrated to be true or false because it has to do with matters of judgment and taste. Compare, for example, the following two statements:

All Singaporeans speak English.

All Singaporeans speak good English.

The first statement is a factual claim. Its truth can be verified by checking whether or not all Singaporeans do in fact speak English. If you find at least one Singaporean who does not speak English, you will have demonstrated that this statement is false and therefore needs to be amended to a statement like Not all Singaporeans speak English or Most Singaporeans speak English. The second statement is identical to the first, except for the presence of the word good, which expresses a value judgment. In the absence of a shared theory about what makes a particular variety of English good or bad, what we have here is an expression of someone’s opinion or taste, which does not fall within the realm of science, including the science of language.

1.6.2 The method(s) of investigation

Scientific investigation typically involves three key activities: observation, analysis and argumentation. Observation consists in looking for patterns in phenomena of various kinds. These patterns are then accounted for in terms of analyses, which typically comprise a set of theoretical constructs, a set of rules describing the observed patterns, and a set of representations that model the observed patterns.

It’s important to bear in mind that a theoretical construct is a hypothetical entity assumed by the scientist in order to explain an observed pattern. Gravity, for example, is one of the best known and most useful theoretical constructs, given its immense explanatory power. Newton’s theory of gravity explains observations both on earth (why things fall) and in space (why planets don’t collide into one another). The constructs that linguists use to explain linguistic phenomena include assumed entities like nouns, verbs, phrases, morphemes and phonemes. We will meet these and other constructs in the remaining chapters of this book, as we explore the structure and use of language in greater detail.

Criteria for evaluating scientific and linguistic analysis

Meanwhile, having looked at the first two activities entailed by the method of scientific investigation (observation and analysis), let’s consider the third, namely, argumentation. Argumentation is necessary in order to critically evaluate alternative analyses. As you know from your own observation and analysis of the world around you, there can be multiple perspectives and explanations for the same phenomenon. How do we decide which analysis is best? Clearly, any disciplinary community needs shared criteria of evaluation. Six criteria that are commonly used to evaluate scientific and linguistic analyses are purpose, accuracy, simplicity, generality, objectivity, and internal consistency. We now deal with each one in turn.

Purpose. Any analysis needs to be motivated, that is to say, it must serve a purpose. The fundamental purpose of scientific analyses is the explanation of observed phenomena, which allows for the prediction of these and other phenomena. A scientific analysis that doesn’t explain anything isn’t a very useful analysis. Neither is an analysis that explains some trivial fact. The latter raises the “So what?” question: So, you discovered X. So what? In other words, scientific researchers need to show how their work contributes to the extant knowledge pool, either by providing new insight on an old problem/puzzle, or by highlighting new frontiers worthy of investigation. If the analysis merely rehashes what is already known, the reaction is likely to be, Tell us something we don’t already know.

Accuracy. One of the key reasons that we seek explanations is in order to make predictions. Obviously, we want our predictions to be correct rather than incorrect. So, one of the basic requirements of an analysis is that it be consistent with our observations, i.e. that it not yield incorrect predictions. For example, if an analysis predicts that X will occur, but what we observe is not X but Y, we have an erroneous analysis, which clearly has to be rejected or amended to accurately capture Y. Analyses typically comprise a set of constructs and a set of rules, expressed as hypotheses to be verified. A hypothesis is a prediction based on an initial set of observations. The purpose of a hypothesis is to be verified (i.e. either confirmed or disconfirmed) through empirical testing. If there is a mismatch between what the hypothesis predicts and what we in fact observe, the hypothesis is disconfirmed, and has to be rejected. In contrast, if what we see is in fact what the hypothesis predicts, we accept the hypothesis provisionally, putting it through further rounds of testing against new sets of data/observations. In both cases, hypotheses help us progress with our investigation. A disconfirmed hypothesis lets us know that the path we took was wrong, and that we therefore should take an alternative route. A confirmed hypothesis becomes a reliable piece of knowledge upon which we can build other hypotheses. .

Simplicity. You may have heard of Occam’s Razor (also known as the law of parsimony or the law of economy), a principle attributed to 14th century logician William of Ockham. Simply put, Occam’s Razor states that the simplest explanation is the best. In other words, when multiple explanations are available for the same phenomenon, the least complicated version is to be preferred, i.e. the one that makes the fewest possible assumptions. For example, hoof beats can be a sign of approaching horses or zebras. According to Occam’s Razor, if one heard hoof beats on a farm, horses rather than zebras would be the preferred explanation, since it requires the fewest assumptions, given what we know about horses and zebras relative to farms. Similarly, burning bushes could be caused by a discarded cigarette or a landing alien spacecraft. Which explanation would you choose, using the simplicity criterion?

Generality. The generality criterion requires an analysis to cover the widest possible range of observations. Why? Because the more general a theory or analysis is, and so the more observations it covers, the fewer theories we need. An analogy might help. One of the reasons we like credit cards is that they can be used for a whole host of transactions, both online and offline. If credit cards didn’t have such general coverage, we would need a whole variety of financial instruments to take care of the different transactions we wish to perform. One of the best known theories, Newton’s theory of gravitational forces, fulfils the generality criterion by explaining observations both here on earth and in space. A less general theory would account only for some observations (e.g. the ones here on earth) but not others. Similarly, if Newton’s theory could only account for some falling bodies (e.g. apples) but not others (e.g. cannonballs or human beings), it would have to be rejected for not being general enough, i.e. for being unable to explain all our observations relating to falling objects.

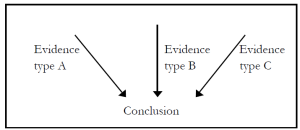

Objectivity. Scientific knowledge is objective in the sense that it is supported by observation and experience rather than by intuition or pure reasoning. Maximal objectivity refers to the use of different types of evidence, or independent sources of evidence, to support a conclusion. This use of multiple types/sources of evidence to establish a conclusion is in turn known as independent corroboration. When various strands of evidence all point towards the same conclusion, we have converging evidence for that conclusion.

Clearly, the more independent reasons there are for accepting a conclusion, the more reliable that conclusion is likely to be. Why? Because each type of evidence would have to be countered for the conclusion to be refuted. Think of two cables: one comprises just one strand of wire, the other comprising multiple strands of wire. Which cable is likely to be stronger? The latter, because one would have to cut through several strands in order to sever the cable. Here’s another example. Let’s say you suspect Jim Jones of murdering his wife. All you have is a gut-feeling that Jones is guilty. No court would accept this subjective evidence as sufficient reason to convict Jones of murder. Now, let’s suppose you manage to obtain eyewitness testimony, placing Jones at the scene of the crime. This would constitute objective evidence. But this evidence could be weakened, if one or more of the eyewitnesses were shown to be unreliable. One way of strengthening your case, then, would be to find an independent source of evidence, implicating Jones in the murder of his wife, e.g. forensic evidence, so that even if the eyewitness testimony were impeached, you would have another source of evidence leading to the same conclusion.

Internal consistency. Whereas the accuracy criterion requires analyses to be free of error, and thus not to yield incorrect predictions, the internal consistency criterion requires analyses to be free of logical contradiction. An analysis that states/predicts both X and not-X would be internally inconsistent, or self-contradictory, because X and not-X are mutually exclusive terms. For example, an entity can be short or tall, but not both, at the same time. It may seem hard to believe that a careful researcher could construct an analysis in which one part of the analysis contradicts another. But the possibility remains, especially with longer analyses.

Linguistics data and ways of acquiring them

Having looked briefly at analysis and argumentation, we return to the central activity in the method of scientific investigation, observation. What is it that linguists observe, and how do they go about collecting their data?

To start with the first question, linguistics data comprise language behaviour as well as speakers’ intuitions about language, produced either by themselves or others. These data can be obtained through observation of naturally-occurring situations or manipulated situations, as in experimentation. In the case of spoken language, naturally-occurring data are typically obtained by observing spontaneous communicative events like conversations, paying attention to the language behaviour of each participant. For example, who opens/closes the conversation? How do speakers signal their wish to change the topic? Who interrupts whom, when and how? Given the ephemeral nature of spoken language, researchers these days often use video or audio technology to record such exchanges. They can then watch/listen to them, transcribe them, and analyse them more accurately. In this sense, analysing written language is a little easier, given that writing leaves a more permanent record than speech. Since the 1980s, however, linguists at various research sites have been building databases or corpora of both spoken and written language (e.g. The British National Corpus, the International Corpus of English) that linguists wishing to investigate naturally-occurring language can access.

In contrast to observing naturally-occurring linguistic behaviour, observation of elicited data typically involves some amount of manipulation, so as to obtain the language behaviour that the researcher wishes to investigate. For example, back in 1958, psycholinguist Jean Berko Gleason wished to investigate the acquisition of the plural rule among English- speaking toddlers, pre-schoolers, and first graders. Gleason (1958) designed an experiment, known as the Wug test, which called for, among other things, the use of the plural. She and her fellow researchers showed each child in the experiment a picture of a pretend creature, and told the child, This is a wug. Next, the child was shown a picture with two of these pretend creatures, and told, Now there are two of them. There are two…. If you’d like to learn more about Gleason’s experiment and her findings, turn to the references at the end of this chapter.

Here’s one more example of observation of elicited data, this time involving adult speakers of English in New York City, in the late sixties. You may have noticed that in words like four, fourth, card, and car, some speakers of English pronounce the /r/ sound represented by the letter ‘r’ in these words, while others drop it. While he was still a graduate student, sociolinguist William Labov (1966) hypothesised that the pronunciation of /r/ in New York English was not random, but correlated to social-class. He predicted that people of higher social status would pronounce /r/ more frequently than people of lower social status. To test his hypothesis, Labov investigated the speech of employees in three Manhattan department stores – an expensive, upper-middle-class store; a mid-priced, middle-class store; and a discount working-class store. In each store, Labov asked various employees for the location of a product which he knew was available on the fourth floor of the store. His question elicited the utterance fourth floor from the employees, and he was thus able to compare their pronunciation. For more about Labov’s experiment and findings, turn to the references at the end of this chapter.

To recap, then, observation of language behaviour, whether naturally- occurring or elicited, is an integral part of the method of linguistic investigation. But language behaviour is only one kind of data that linguists are interested in. Other data include speakers’ intuitions about their language, typically obtained through questionnaires or interviews, or through introspection. The latter refers to linguists consulting their own intuitions about a language, when they happen to speak the language they wish to investigate. As mentioned in section 1.2, however, linguists do not need to speak the language they wish to investigate. If you’re wondering how linguists can be credited with providing trustworthy descriptions of languages that are alien to them, think about how doctors discover what is ailing their patients. Doctors don’t need to be suffering from a particular disease in order to investigate it. What they do is examine patients and ask questions that allow them to infer the nature and cause of the disease. Likewise, linguists examine available language behaviour and ask native speakers about their intuitions concerning language. This is what we (the authors of this book) would have to do, if we wished to propose a credible description of Singapore English or Jamaican English, for example, not being native speakers of these varieties of English ourselves. We would both observe the language behaviour of native speakers of these varieties and obtain their intuitions about their language use in order to propose an analysis of the grammar of Singapore English and of Jamaican English, respectively. Our own use of English would tell us only about the varieties of English that we speak, and little or nothing about the variety of English spoken by Singaporeans and Jamaicans.

1.6.3 The purpose of investigation

As mentioned in section 1.5, the purpose of scientific investigation is to explain observed phenomena as simply, generally, and objectively as possible, so that we can not only satisfy our curiosity about the world around us, but also adapt to it by being able to predict events reliably.

At the beginning of this chapter, we also highlighted that in defining/exploring any object, it is possible to focus on form or function. Needless to say, if we are to achieve a holistic understanding of the nature of language, we need to consider both aspects, since function influences form, and vice versa. Given the complex interplay between form and function, it would be virtually impossible to find a branch of linguistic investigation that adopts an exclusively formal or functional perspective.

Moreover, given how language permeates human activity, its study affects and is in turn affected by virtually every other area of human interest. The study of language today tends to be approached from the perspective of many different sciences and professional fields, from which linguists draw knowledge and to which they contribute practical and theoretical insight. Some of these interdisciplinary areas of research include:

- Anthropology: language and culture; ethno-linguistics

- Child studies: language acquisition and development

- Computer science: programming languages; machine translation; “thinking” machines; computational linguistics

- Education: language teaching

- Dentistry: orthodontics and speech

- History: language change over time; historical linguistics

- Law: forensic linguistics

- Mathematics: formal systems of communication

- Medicine: language, mind and brain; neurolinguistics; language pathology

- Music: the singing voice

- Philosophy: language and reasoning

- Physics: voice acoustics; speech synthesis; voice recognition

- Psychology: language and cognition; psycholinguistics

- Rhetoric: language and persuasion

- Sociology: language, ideology, and power; sociolinguistics; critical discourse analysis

In this chapter, we looked briefly at the nature of linguistics as the science of language, to systematically observe and explain language structure and use. We also considered two notions of language – as language faculty (Saussure’s langage) and its manifestation in individual languages (Saussure’s langues). We might think of these two notions of language as two sides of the same coin. That is to say, no matter what the differences between individual languages, there must be certain shared universal features, given that every language must conform to the constraints of the human brain and of human communicative needs. Conversely, the study of language as a universal human phenomenon can only proceed through the study of individual languages. The next chapter considers this relationship between language and languages more closely.

Food for thought

On language

“It is a very remarkable fact that there are none so depraved and stupid, without even excepting idiots, that they cannot arrange different words together, forming of them a statement by which they make known their thoughts; while, on the other hand, there is no other animal, however perfect and fortunately circumstanced it may be, which can do the same.”

René Descartes (1637). Discourse on the method.

“If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1921). Tractatus logico-philosophicus.

“It is certainly the business of a grammarian to find out, and not to make, the laws of a language.”

John Fell (1784). An essay towards an English grammar.

Reprinted 1974, London: Scolar Press.

On the nature of scientific investigation

“How do we know?”

“The act of observing affects the observed.”

##

Werner Heisenberg

“It’s a commonly held view that ‘facts’ are just lying about in the world, and the way we make theories is by collecting these facts and then seeing what theories they lead to. Nothing could be further from the truth: in a way, there are no facts without theories. One might even define a theory as – in part – a framework that tells you what a fact is.”

Roger Lass (1998). Phonology. An introduction to basic concepts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 6.

“… most writing about [science] focuses only on the answers. People cannot make sense of answers if they do not first understand the questions. Solutions only have meaning if one has a firm grasp of the problems being addressed, and of why these problems matter.

Why, for instance, does it matter if the earth revolves around the sun or the sun around the earth? In most physics books, and in most classrooms, this is presented as a problem in celestial geometry: Is it the blue dot or the yellow one at the center? With virtually no sense of context we are told that Copernicus finally “solved” this problem by placing the yellow dot in the central position. To most students the whole exercise appears little more than an abstract mathematical game.

Yet the issue matters greatly. The question of whether the sun or the earth is at the center of the cosmic system is not just a matter of celestial geometry (though it is that as well), it is a profound question about human culture. The choice between the geocentric cosmology of the Middle Ages and the heliocentric cosmology of the late seventeenth century was a choice between two fundamentally different perceptions of mankind’s place in the universal scheme. Were we to see ourselves at the center of an angel-filled cosmos with everything connected to God, or were we to see ourselves as the inhabitants of a large rock purposelessly revolving in a vast Euclidian void? The shift from geocentrism to heliocentrism was not simply a triumph of empirical astronomy, but a turning point in Western cultural history.”

Margaret Wertheim (1997). Pythagoras’ trousers. God, physics, and the gender wars. London: Fourth Estate, p. xii.

“… we [the non-scientists] may not be able to follow the details of the scientists’ proofs, but we are entitled to explanations we can understand.”

Lisa Jardine (2000). Ingenious pursuits: building the scientific revolution.

London: Abacus, pp. 364-365.

“… to my mind by far the greatest danger in scholarship (and perhaps especially in linguistics) is not that the individual may fail to master the thought of a school but that a school may succeed in mastering the thought of the individual.”

Geoffrey Sampson (1980). Schools of Linguistics. Competition and evolution.

London: Hutchinson, p. 10.

Further reading

Brinton, Laurel J. (2000). Chapter 1. The nature of language and linguistics. In The structure of modern English: A linguistic introduction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3-11.Crystal, David (1986). Chapter 2. What linguistics is. In What is linguistics? (4th ed.) London: Edward Arnold, pp. 24-52.In Science We Trust. (2002, December). Scientific American. Editorial, p. 4.Napoli, Donna Jo (2003). Part I. Language: The human ability. In Language matters: A guide to everyday thinking about language. New York: Oxford University Press.

References

Gleason, Jean B. (1958). The child’s learning of English morphology. Word 14, 150-177.

Humboldt, Wilhelm von (1836/1999). On language. The diversity of human language-structure and its influence on the mental development of mankind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Labov, William (1966). The social stratification of English in New York City. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Saussure, Ferdinand de (1915/1974). Course in general linguistics. Eds. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye in collaboration with Albert Reidlinger. Translated from the French by Wade Baskin. London: P. Owen.

Wierzbicka, Anna (1992). Semantics, culture, and cognition: Universal human concepts in culture-specific configurations. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Attribution

This chapter has been modified and adapted from The Language of Language. A Linguistics Course for Starters under a CC BY 4.0 license. All modifications are those of Régine Pellicer and are not reflective of the original authors.