Chapter 7: History of English

History of English

Chapter Preview

In this unit you will:

• Learn the history (and some very interesting stories) of English from Olde English, Middle English, and Early Modern English time periods

• Listen to Olde, Middle, and Early Modern English as it was spoken

• Practice speaking some of each time period

The history of our language is a colorful and exciting one. To begin, our language has not always sounded like it does today. Believe it or not, to today’s speaker of English, our language may have sounded much more like German and Latin from its origins.

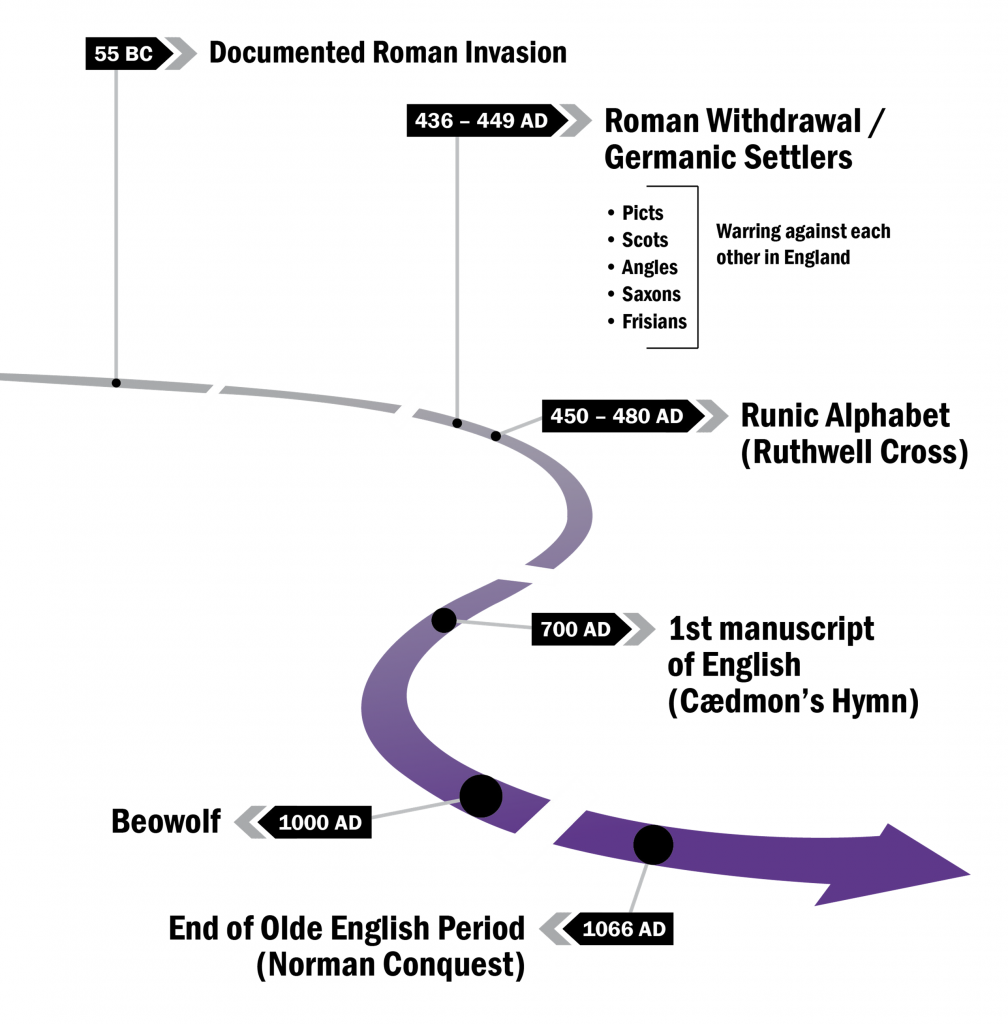

Olde English

A Little History

Rome

When Rome was in the process of conquering the world, Englalond (England), was very much in their sights. Mostly because England has strong sea ports and trade routes already in place.

By the 1st century AD, the Roman Empire governed all of the Italian peninsula, Romania, Switzerland, England, France, and most of the Mediterranean region as well as parts of North Africa.

Language:

- Romans forced language change in many ways, but primarily through forcing merchants to do all their trade in Latin.

- Soon after infiltrating the commerce, they forced the use of Latin in government.

- Next, they forced the use of Latin in religion and education.

The Germanic Invasion

Rome Leaves England

Why was Latin not the “common” language?

Consider what you know already about the way the Romans forced the Latin language. Why, then, when the English went home, did they not speak Latin?

Scandinavian Influences

The Scandinavians influences in the English language from about 700 to 1066 have

remained, for the most part, unchanged. They include:

Patronymics:

The idea of knowing who you are based on your father’s name. For example, if your father’s name was Peter, you become Peter’sson or Peter’stadtter. So, Leonard Hofstadter (of The Big Bang fame) is actually an ancestor of a man whose name was Hof, who had a daughter!

Personal Pronouns:

The Scandinavians brought with them the idea of third person plural pronouns.

The words include: they, them, their, and themselves. Can you imagine carrying on a conversation without those pronouns?

“sk”

Most interesting is the sound signified by the Scandinavian letters [s k]. There is a story, that may or may not be true, the name for the garment ‘skirt’or ‘skyrta’ was pronounced [sh ee r t a] by the Scandinavians. Now this was confusing for the English who also had a word ‘scyrte’ which was pronounced [sh ee r t uh]. So, to reduce the confusion, the English began pronouncing the ‘sc’ as we would pronounce the ‘sk’ today and ‘scyrte’ became ‘skirt’ and ‘skyrta’ became ‘shirt’.

Interesting note: in many Norwegian countries today the ‘sk’ sound is pronounced [sh].

Place Names:

Many places in England were named by the Scandinavians. They used suffixes, such as: by, thwaite, and dale.

Dal(e): to signify a valley

Thwaite: to signify a place in or near a meadow

By: to signify who owned the property

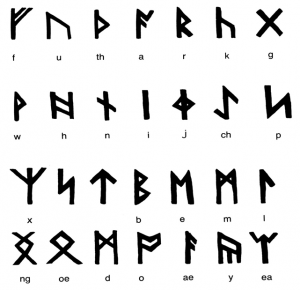

Ruthwell Cross (refer to Roman Occupation map above)

The story of the Ruthwell Cross and the story written on it is very important to our language.

The Ruthwell Cross gives us one of the first poems written in the Runic alphabet. This cross tells the story of Christ and his walk to Golgotha. What is most interesting is that this poem is told from the perspective of the cross.

The title of the poem is “The Dream of the Rood.” Rood in Olde English translates to wood.

“Krist wæs on rodi. Hwethræ ther fusæ ferran kwomu æththilæ til anum.”

Runes

It is not known exactly why the Runes have faded from existence. What is important, is that the pagan peoples who lived in the northern part of England, what is now Scotland, used this alphabet and now do not.

As English speakers and writers, have you considered what it might be like if English people had continued using this alphabet instead of the Roman alphabet?

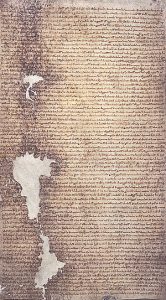

Caedmon’s Hymn

The story of Caedmon’s Hymn is one of a man who wanted to be a priest. In the days of the Olde English time period, it was expected that priests would sing and write their own music. Caedmon was not talented in either of these (or so the story goes). He was a simple cow/sheep herder. His lifelong dream was to live among the priests at the abbey.

However, one night, while Caedmon slept, he had a dream that he wrote a song. He quickly shared this with the leader of the abbey where he lived.

His hymn is the oldest poem written in English. It is dated to approximately 658 and 680.

Musical Composition of the West Saxon version of Caedmon’s Hymn, lyrics by Caedmon; music and performance by Clay Paramore, with Laura Aaron on piano. CC0.

| Northumbrian

Nū scylun hergan hefaenrīcaes Uard, |

West Saxon

Nu sculon herigean heofonrices weard, He ærest sceop eorðan bearnum |

| English translation (Carol Russell)

Now we must praise the Guardian of heaven, The mighty Creator, and his creation The work of the Glorious Father, just as The mighty Lord began to establish his wonders. He, the Holy Creator, first fashioned the Earth for His children With heaven as a roof. Then mankind’s Guardian, the almighty Lord, Afterwards adorned the earth with men. |

|

Olde English Translation

Remember, in this time period, the vowels were nearly opposite of what we have today. Also, some of the sounds are different as well.

If you pay close attention to switching vowels and the information you know already from Caedmon’s Hymn, you should be able to translate this poem as well.

Original – This text is presented in the standardised West Saxon literary dialect.

[1] Fæder ure þu þe eart on heofonum,

[6] and forgyf us ure gyltas, swa swa we forgyfað urum

Olde English Words

| Nature | Animals | Concepts | People |

|---|---|---|---|

| æcer - field | ǽl - eel | áð - oath | beorn - warrior |

| bæst - bast | bár - boar | borg - pledge | bydel - beadle |

| béam - tree | bucc - buck | céap - price | ceorl - churl |

| beorg - hill | bulluc - bullock | coss - kiss | cniht - boy |

| blóstm - blossom | earn - eagle | cræft - skill, strength | cyning - king |

| bóg - bough | eoh - horse | cwealm - death | dweorg - dwarf |

| bolt - bolt | eolh - elk | dóm - doom | eorl - nobleman |

| bróm - broom (the plant) | fearh - pig, boar | dream - joy, revelry | gást - spirit |

| clam - mud | fisc - fish | fæðm - embrace | hæft - captive |

| clút - patch | forsc - frog | fléam - flight | hwelp - whelp |

| cnoll - knoll | fox - fox | gang - going | m?g - kinsman |

| codd - cod, husk | géac - cuckoo | gielp - boasting | þegn - thane |

| cropp - sprout | h?ring - herring | hlæst - burden | þéof - thief |

| forst - frost | hengest - horse | hréam - cry, shout,uproar | wealh - foreigner |

| hægl - hail | hund - dog | torn - grief | wer - man |

| hærfest - autumn | hwæl - whale | þanc - thought | |

| healm - haul | mearh - horse | wæstm - growth | |

| hláf - loaf | seolh - seal (animal) | ||

| horh - dirt | swertling - titlark | ||

| hrím - rime | wulf - wolf | ||

| hýdels - hiding place, cave | |||

| mæst - mast | |||

| mór - moor | |||

| múð - mouth | |||

| regn - rain | |||

| sealh - willow | |||

| slóh - slough, mire | |||

| stán - stone | |||

| storm - storm | |||

| stréam - stream | |||

| swamm - swim |

Order of Events

| January | Edward | English |

| January-October | Harold | Anglo Saxon |

| October-December | Edgar | Hungarian |

| December 23rd | William | French |

Edward is King until his death in January

- True “Anglo Saxon”

- Childless – uh oh- no heir apparent.

The Cast

The Conflict

There’s the rub! King Edward has no children, but he does have a brother-in-law, Harold. Harold with an ‘o’. So, he is ‘elected’ king. Elected by the Court, not the people.

The conflict continues as there are others who claim the throne, too.

- First, William of Normandy, who has some distant claim, that may not be strong

- Also, Edgar of Hungary, has a mother who is certain he has a claim to the throne

- Next in line is Harald of Norway also claims to be successor, as well

The Plot Thickens

From April to September forces gather against each other

Harold had a brother (Tostig). He was estranged and lived in France. He sided with Harald and fought battles with him.

Harold had the support of the Normans. Remember, they are French.

William began gathering the Germanic peoples from villages all across England. By September he has a very strong army.

He has the support of nearly all of England’s commoners. He cannot seem to conquer London.

NOTE: London is the seat of Government, Education, Religion. It has the busiest ports, and had the most inhabitants of all major cities.

Through the months of September-December

Harold defeated and killed Harald and Tostig. William, however, loses London, but the rest of England submits to his power.

And then, Harold dies in battle—William looks like he might have England.

But WAIT!

When Harold dies, England has no ruler.

Parliament names a boy of 14, who is a distant relative of Harold, king. His name is Edgar. He is Hungarian!

… And Then!

William defeats the Norman stronghold in London. He is crowned King on Dec. 23, 1066. There you have it…four rulers in one year. Two Anglo Saxon, one Hungarian, one French. This year, 1066, began for England two things. The first, the concept of pride of nationality. William helped with that by gathering the villagers together. The second was the idea that the aristocracy would befriend the French, or hate them. Depending on who was King or Queen, would depend on the relationship between England and France. The English language took (borrowed) words from the French, and the English aristocracy copied fashion, cuisine etc.

Middle English

Middle English Timeline

Changes begin!

It is during this time English leaders, who are sometimes French and sometimes English, either accept French influences or resist them.

One of the biggest changes in England when we move away from Olde English to Middle English is that we begin our love/hate relationship with the French.

The earliest date of surviving written texts in Middle English dates to approximately 1150.

Much is happening in England during this time period. Oxford is founded as is Cambridge University.

By the late 1200’s, English becomes the most common language spoken in England. By the 1300’s the Great Vowel Shift begins changing English into something more akin to what our ears are accustomed to hearing.

The Great Vowel Shift occurs over several generations and about 100 or so years.

The Great Vowel Shift

A VERY basic way to remember is that all short vowels became long and all long vowels became short

Dracula’s law: 3rd shift=Blood, 2nd shift=good, 1st shift=food

“Blood is good food.” In Olde English it was “Blod is gud foud.

Is this another “Great Vowel Shift”?

Today in the Northern Great Lakes region of the US there is a vowel shift going on! “Bus” sounds to many Midwesterners like “Boss”

Chaucer 1342-1400: The Canterbury Tales

Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

5 Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

10 That slepen al the nyght with open eye-

(So priketh hem Nature in hir corages);

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

15 And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke

That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke.

This is an excerpt of the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, 1386, written by Geoffrey Chaucer. It is a story of a group of people traveling together to visit religious sites in Canterbury, England.

Chaucer’s English, although not entirely like Modern English, has more similarities than Olde English. As you can see (left), there are many more words that look and sound like modern English.

Notice, too, that the Great Vowel Shift has not been completed at this point.

CC BY, Ancient Literature Dude, The Canterbury Tales General Prologue, complete reading (Middle English, with timestamps)

Caxton’s Press

Caxton was an inventor, merchant, and ultimately a printer. In his travels as a merchant, he was intrigued with a printing press he saw in Cologne, France. He stayed there until he learned how to print pages.

He traveled back to England, where he built his own printing press and set up shop in Westminster Abbey.

The first book to have been printed on this press is Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

He is also credited for printing the first Bible verses on his press, as well.

Loan Words

Between 1300-1400

- The English language acquired 10,000+ loanwords

- 75% still used today

Pronunciation is changed due to outside influences – namely loanwords

- 31% of the loanwords are French

- Remaining – Latin, Scandinavian, Other

In the 1300’s English acquires many more words that are added to the lexicon. Among the most used words today nearly 50% come from French or Latin. Although we credit many words from Scandinavian influences (remember they gave us place names and pronouns!)

Exercises

Using the list below, try to choose words in that category that you believe are NOT borrowed from another language.

- Government:

- Religion:

- Law:

- Military:

- Fashion:

- Food:

- Society:

- Art:

- Architecture:

- Literature:

- Medicine:

Orthographic Lag

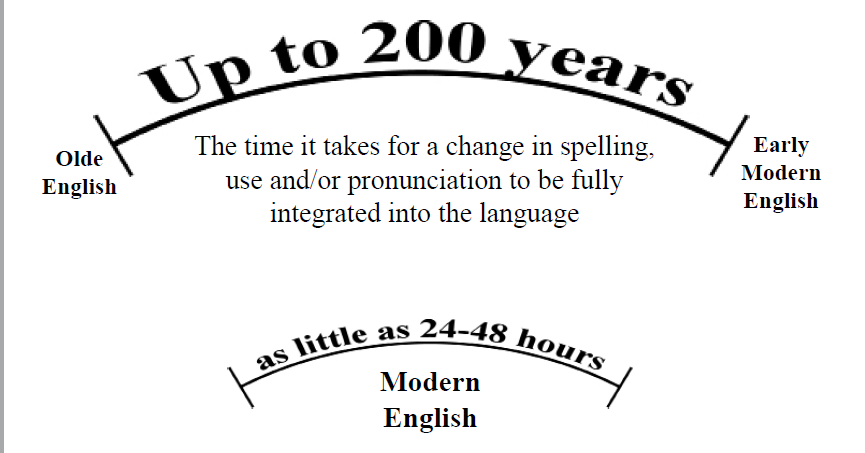

Orthographic Lag is the time it takes for a word, a pronunciation, or phrase to be added to the language and to become a permanent part of the lexicon.

…THINK ABOUT THIS:

Why would the orthographic lag be reduced to such a short amount of time?

Pronunciation Guide

In order to pronounce Middle English, speakers need only remember that vowels are not always pronounced the same as they are today.

One thing that will help you pronounce Middle English is to remember to drop the jaw and fully open the mouth when pronouncing vowels.

Use the following chart and practice on your own. In no time, you will be able to read The Canterbury Tales in its original version!

| VOWEL SOUNDS | a = ah | e = ay | i / y = ee | o = oh | u = ôô |

| Symbol | As In: | Spelling | Examples: | |

| ä = ah | father | a, aa, er | fader, name, that, ferther, clerk, sterte | a |

| æ | hat, pass | a, ae | has, begge, great, heeth, baebe | |

| ay / ey | mate, day | e, ee | grene, sweete, me, be, she, fredom | e |

| ah-ee * | aisle | ai, ay, ei, ey | day, lai feith, veyne | |

| i * | my | ai, ay, ei,ey | fair, may, feith | |

| ar | there | e, ea | bere, sea | |

| a | sofa | first or final e | sonne, chivalrie, cause, yonge, name | |

| e | met | e, ee | ryden, hem, end, gentil | |

| ee-oo | few | eu, ew, u | new, reule | |

| ee | machine | i, y | passioun, shires, blithe, nyce, wif, ryde, icumen | i |

| i | bit | i, y | yloved, list, nyste, skille | |

| au | cloth | o, oo | lore, goon, ofte, hooly | |

| o = oh | sow, note | o, oo, ou, ow | bote, good, roote, thought, knowe | o |

| oo | root | u, ou, ow | juggen, resoun, flour, fowles, hous, vertu | u |

| o | book, full | o, oo, u | ful, nonne, love | |

| ah-oo | house, how | au, aw | cause, drawe | |

| aw-uh | Paul, awl | ou, ow | knowen, soule | |

| oy | boy | oi, oy | joye, point, coy |

Early Modern English

The Beginning of Modern English

The Age of Reason Begins

By the time the Middle Ages pass there is a transformation of thinking. People are free, now, to pursue personal enlightenment and knowledge.

During the early 1600s, English is now, not only spoken in England, but is transplanted to North America with the founding of Jamestown.

This also pushes the Age of Reason into the colonies. As man felt the call to find his own path in regards to religion, many felt they must leave England to do so.

It was during this time that leaders in circles of intellect and writing begin calling for changes in how the English view their language. Prescriptivism is born.

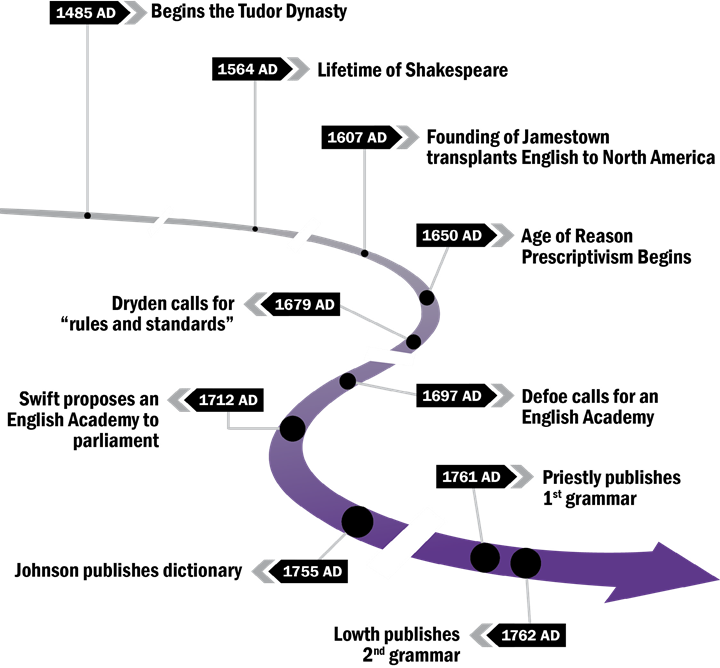

Early Modern English Timeline

The Age of Reason: The Early Prescriptivists

1564-1616 Lifetime of Shakespeare

Although not always considered one of the founding Prescriptivists, Shakespeare did influence the language of those early Prescriptivists. He made up words, definitions, etc., which certainly may have helped those who were on the mission to set and refine the English language.

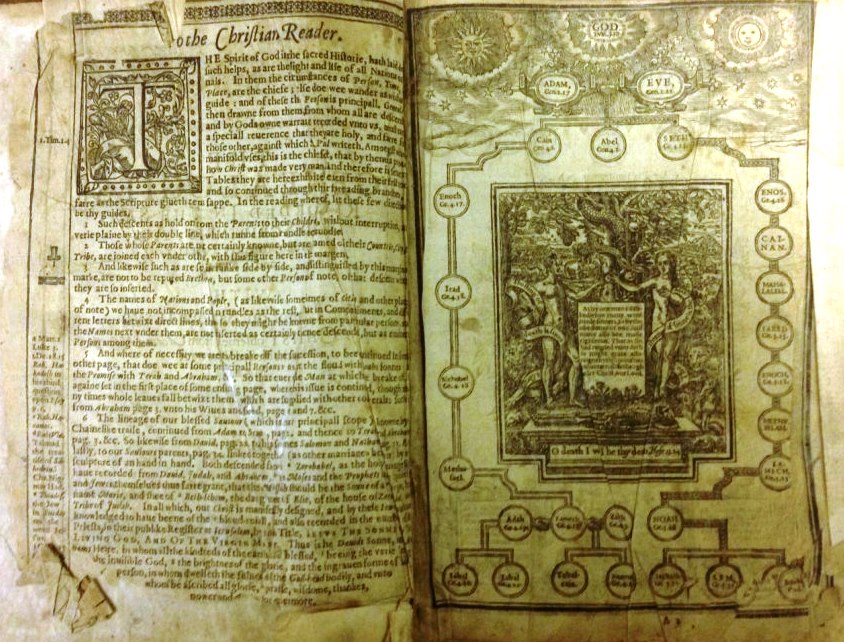

1611 King James Bible

Some claim that the King James Bible was printed on Caxton’s Press. It is possible.

One interesting note is that Samuel Johnson’s did use King James’ Bible as a source for his definitions in his early editions of his dictionary.

1679 Dryden wants “rules and standards”

John Dryden was most noted as being a straight forward poet and writer. Many claim that it is Dryden who established the rule that English sentences should not end in prepositions. He believed that standards for English would enhance not diminish its function.

1697 Defoe proposes an English Academy

Daniel Defoe is most famous for his novel, Robinson Crusoe. He was a prolific pamphleteer. He was imprisoned for a libel case. Yet he wrote in favor of creating an Academy in which English be established as the formal language of the unified England.

1712 Swift Proposes an English Academy to parliament

Jonathan Swift also wanted an academy and proposes the idea to Parliament. He believed in the power of the people and wanted a country where national pride was foremost.

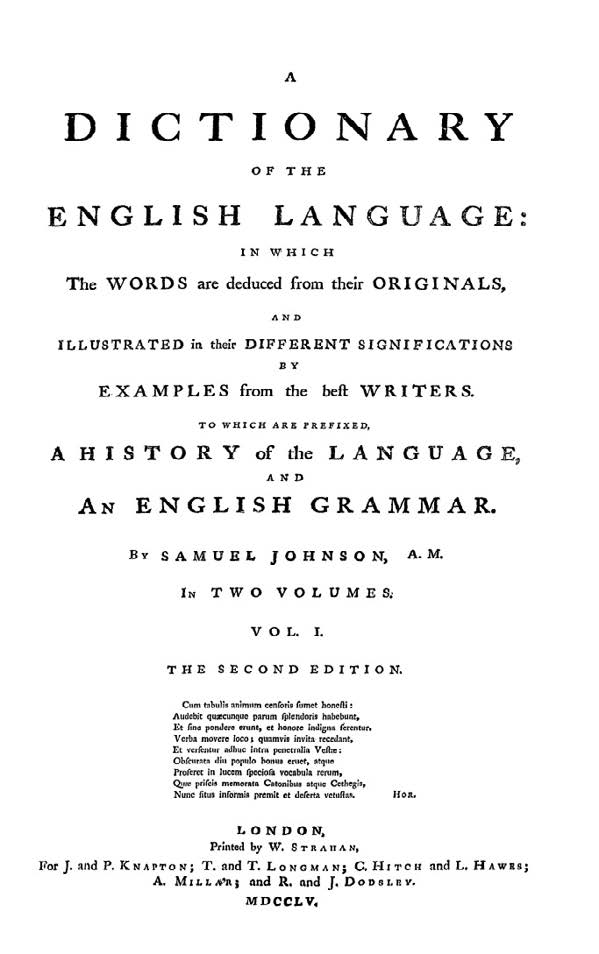

1755 Johnson publishes dictionary

Samuel Johnson writes the first English dictionary. He was under contract to write his dictionary in 1746. It was published in 1755. He was known to state that what took the French Academy nearly 40 years to do for their language was accomplished by one man in only 9 years.

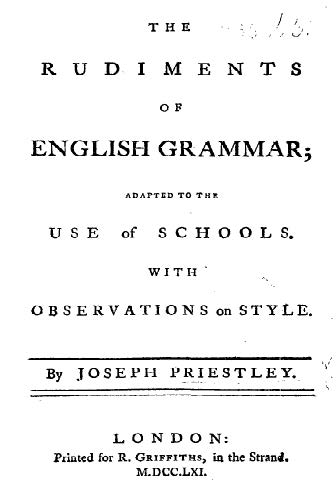

1761 Priestley publishes first grammar book

Joseph Priestley is the first to write a book on English grammar in, Rudiments of English Grammar.

1762 Lowth publishes second grammar book

Just a year later, Robert Lowth publishes his grammar book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, With Critical Notes.

It is from these men we have what is called Prescriptivism, today. These men wanted to prescribe for its speakers what the English language ought to be and to refine the language. They sought to keep language in a fixed and permanent state.

Prescriptivism

What is Prescriptivism?

Prescriptivism is prescribing language.

It is how a group of 6 men wanted to ‘fix’ the English language in a permanent way. To put language in a box and keep it from changing.

What these six guys stood for was order and regulation.

What they did not sanction among many others was clipped words, contractions, and slang.

Think of the language we speak today. Can you imagine speaking and never using a contraction or a word that has been clipped?

And, oh my, the slang we use today! I imagine the 6 guys would turn over in their graves to hear the language we use today.

End Results

The end result of prescriptivism left people thinking that language must be fixed. Prescriptivism did not allow for changes in the language either in pronunciation or spelling. Prescriptivism sought to logically order language using grammar rules and regulations, which we have adopted and maintained ever since.

The Growth of our Lexicon

Derivation

These kinds of words are very common and have been useful in creating ways of speaking and being understood.

You begin with a root word like ‘lock’. By adding a prefix or a suffix a new word can be created.

This is especially helpful in understanding if some can or cannot be done, in this case, locked.

Examples

How to make:

root word + suffix/prefix = new word

UN+LOCK+ABLE = Unlockable

Compounding

These kinds of words are very common today. Compounding begins with two words that do not have anything in common.

In this case a neck and a lace. By combining the two, we get a new word ‘necklace’.

Another favorite is dug and out. Yet, when we compound them, we get a new noun which we all know as dugout.

Examples

How to make:

Word A + Word B = Word AB

Neck + Lace = Necklace

Attribution

This chapter has been adapted from Linguistics for Teachers of English by Carol Russell under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.