22 Frank Edwards Account of the Texas Rangers.

This is an excerpt from the diary of Frank Edwards, who marched with Alexander Doniphan’s army from New Mexico to Nuevo León during the U.S.-Mexico War. He witnessed and described executions by Texas Rangers in northern Mexico.

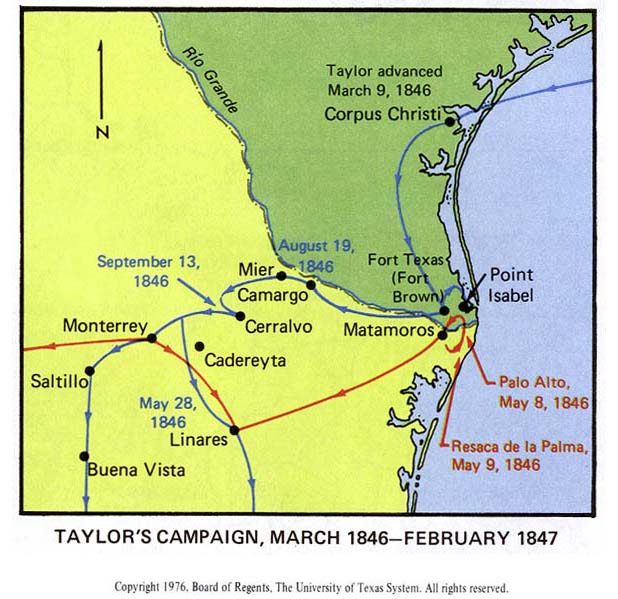

Taking a stroll through the town of Cerralvo (Nuevo León), I found, sitting under a tree, dealing monte (a popular card game of the time), a genuine specimen of the Texian (early word for Texan) Ranger. His name, he said, was John Smith – a name which I thought I heard before. In height he was about six feet four inches of a stout sinewy frame, dressed in a mongrel attire, his coat being of American manufacture, his pantaloons Mexican, and his belt Indian. A fine white shirt, open some distance down, tied with a black silk handkerchief, studiedly knotted, and a Mexican sombrero completed his dress.

By his side was his younger brother, about fifteen years old, dressed, with little variation, in the same style, with two enormous silver-mounted holster pistols in his waist, one under each arm. The elder had a quantity of silver buttons and little ornaments on his hatband and clothes; while on the faces of both, the word desperado was indelibly stamped.

I sat down by John Smith and drew him into conversation, he told me that the United States did not give the Rangers any rations either for man or horse, but paid an equivalent and that they procured their subsistence out of the Mexicans. And the process of doing this he graphically described;

“Waal, you see when we want anything, a few if us start off to some rich hacienda near here, and tell the proprietor we must have so much of provisions. Waal, of course he don’t like that so much, so he refuses. One of us just knots a lasso ‘round the old devil’s neck, and fastens it to his saddle-bow; first passing it over the limb of some tree; then mounting his horse he starts off a few feet giving him a hoist, and then returns dropping him down again. After a few such swings, he soon provides what we have called for. Perhaps you think we’ve done with him then, eh? Not by a long shot. We have to jerk him a few times more, and then the money or gold dust is handed out. When we’ve got everything out of him we let the yellow devil go. We don’t hurt him much, and he soon gets over it.”

Who can wonder at the Mexican becoming a guerrilla?

I’ve been credibly informed that when these Rangers are sent out on scouting parties, a Mexican guide is generally provided, but he never returns; the Texians always shooting him on some pretext or other before he gets back. Their usual mode is to frighten him with threats, and, after putting him under guard, to have one of their number go up to the poor fellow, and advise him to run off immediately he sees the sentinel’s back is turned. This he does, and the sentinel, having received his cue, shoots him while attempting to escape.

One of the most dastardly acts I ever heard of was perpetrated by half a dozen Texian officers a short time before we came down. They had lost their way, and hired a Mexican to show him to their camp, which he faithfully performed; but when they came in sight of it, they drew lots to see who should shoot their faithful and unsuspecting guide – the one on whom the lot fell, immediately drew a pistol and shot him.

Most of these Rangers are men who have been either prisoners in Mexico, or, in some way, injured by Mexicans, and they, therefore, spare none, but shoot down every one they meet. It is said that the bushes, skirting the road from Monterrey southward, are strewed with the skeletons of Mexicans sacrificed by these desperadoes.

While we rested at Cerralvo, I witnessed the execution of a Mexican supposed to be one of Urrea’s lawless band. The Texians pretended to consider him as such; but there was not doubt this was only used as a cloak to cover their insatiable desire to destroy those they so bitterly hate. A furlough was found upon this Mexican, from his army, to visit his family, ending as our furloughs do, that should he overstay his leave of absence, he would be considered a deserter. This time he had considerably overstayed; and he himself stated that he had never intended to return, being in favor of the Americans. But the Rangers tried him by a court-martial; and adjudged him to be shot that very day. As the hour struck, he was led into the public plaza; and five Rangers took their post a few feet off, as executioners. The condemned coolly pulled out his flint and steel, and little paper cigarito; and, striking a light, commenced smoking as calmly as can possibly be imagined and – in two minutes – fell a corpse, with the still smoking cigarito yet between his lips. I did not see a muscle of his face quiver, when the rifles were leveled at him, but he looked coolly at his executioners, pressing a small cross, which hung to his neck, firmly against his breast. I turned from the scene sickened at heart.

Frank Edwards, A Campaign in New Mexico with Colonel Doniphan, (London: Hodson, 1848). (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433115687398)