26 Ben Kinchlow’s Narrative, A Slave in Brownsville and Freedman in South Texas

Ben Kinchlow gave an interview as part of a federal project to record the oral histories of former slaves. In this Works Progress Administration narrative, Kinchlow recounted his youth as a slave and early adulthood as a freedman and rancher. As with many such narratives, the interviewer attempted to replicate the speaker’s dialect through spelling.

Ben Kinchlow’s Narrative

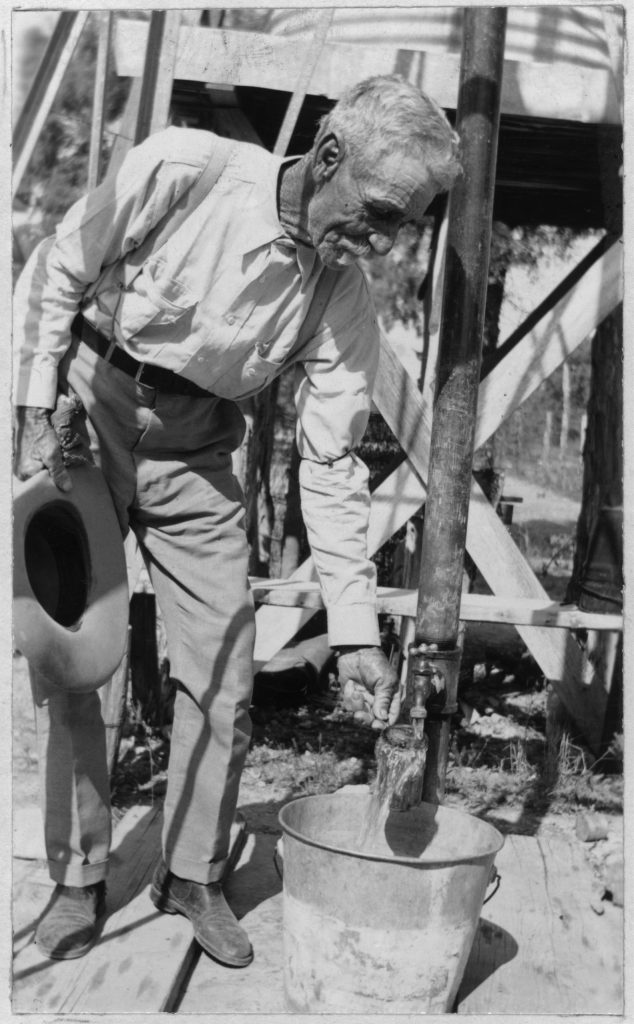

Ben Kinchlow, 91 (in 1937), was the son of Lizaer Moore, a half-white slave owned by Sandy Moore , Wharton Co., and Lad Kinchlow, a white man. When Ben was one year old his mother was freed and given some money. She was sent to Matamoros, Mexico and they lived there and at Brownsville, Texas, during the years before and directly following the Civil War. Ben and his wife, Liza , now live in Uvalde, Texas, in a neat little home. Ben has straight hair, a Roman nose, and his speech is like that of the early white settler. He is affable and enjoys recounting his experiences.

“I was birthed in 1846 in Wharton, Wharton County, in slavery times. My mother’s name was Lizaer Moore. I think her master’s name was Sandy Moore , and she went by his name. My father’s name was Lad Kinchlow . My mother was a half-breed Negro; my father was a white man of that same county. I don’t know anything about my father. He was a white man, I know that. After I was borned and was one year old, my mother was set free and sent to Mexico to live. When we left Wharton, we was sent away in an ambulance. It was an old-time ambulance. It was what they called an ambulance — a four-wheeled concern pulled by two mules. That is what they used to traffic in. The big rich white folks would get in it and go to church or on a long journey. We landed safely into Matamoros, Mexico, just me and my mother and older brother. She had the means to live on till she got there and got acquainted. We stayed there about twelve years.

Then we moved back to Brownsville and stayed there until after all Negroes were free. She went to washing and she made lots of money at it. She charged by the dozen. Three or four handkerchiefs were considered a piece. She made good because she got $2.50 a dozen for men washing and $5 a dozen for women’s clothes. I was married in February, 1879, to Christiana Temple, married at Matagorda, Matagorda County. I had six children by my first wife. Three boys and three girls. Two girls died. The other girl is in Gonzales County. Lawrence is here workin’ on the Kincald Ranch and Andrew is workin’ for John Monagin’s dairy and Henry is seventy miles from Alpine. He’s a highway boss. This was my first wife. Now I am married again and have been with this wife forty years. Her name was Eliza Dawson . No children born to this union.

The way we lived in those days the country was full of wild game, deer, wild hogs, turkey, duck, rabbits, ‘possum, lions, quails, and so forth. You see, in them days they was all thinly settled and they was all neighbors. Most settlements was all Mexicans mostly; of course there was a few white people. In them days the country was all open and a man could go in there and settle down wherever he wanted to and wouldn’t be molested a-tall. They wasn’t molested till they commenced putting these fences and putting up these barbwire fences. You could ride all day and never open a gate. Maybe ride right up to a man’s house and the just let down a bar or two. Sometime when we wanted fresh meat we went out and killed. We also could kill a calf or goat whenever we cared to because they were plenty and no fence to stop you. We also had plenty milk and butter and home-made cheese. We did not have much coffee. You know the way we made our coffee? We just taken corn and parched it right brown and ground it up. Whenever we would get up furs and hides enough to go into market, a bunch of neighbors would get together and take ten to fifteen deer hides each and take ’em in to Brownsville and sell ’em and get their supplies. They paid twenty-five cents a pound for them. That’s when we got our coffee, but we’d got so used to using corn-coffee, we didn’t care whether we had that real coffee so much, because we had to be careful with our supplies, anyway. My recollection is that it was fifty cents a pound and it would be green coffee and you would have to roast it and grind it on a mill. We didn’t have any sugar, and very rare thing to have flour. The deer was here by the hundreds. There was blue quail my goodness! You could get a bunch of these blue top-knot quail rounded up in a bunch of pear and, if they was any rooks, you could kill every one of ’em. If you could hit one and get ‘im to flutterin’, the others would bunch around him and you could kill every one of ’em with rooks. We lived very neighborly. When any of the neighbors killed fresh meat we always divided with one another. We all had a corn patch, about three or four acres. We did not have plows; we planted with a hoe. We were lucky in raisin’ corn every year. Most all the neighbors had a little bunch of goats, cows, mares, and hogs. Our nearest market was forty miles, at old Brownsville.

When I was a boy I wore what was called shirt-tail. It was a long, loose shirt with no pants. I did not wear pants until I was about ten or twelve. The way we got our supplies, all the neighbors would go in together and send into town in a dump cart drawn by a mule. The main station was at Brownsville. It was thirty-five miles from where they’d change horses. They carried this mail to Edinburg, and it took four days. Sometimes they’d ride a horse or mule. We’d get our mail once a week. We got our mail at Brownsville. The country was very thinly settled then and of very few white people; most all Mexicans, living on the border. The country was open, no fences. Every neighbor had a little place. We didn’t have any plows; we planted with a hoe and went along and raked the dirt over with our toes. We had a grist mill too. I bet I’ve turned one a million miles. There was no hired work then. When a man was hired he got $10 or $12 per month, and when people wanted to brand or do other work, all the neighbors went together and helped without pay.

The most thing that we had to fear was Indians and cattle rustlers and wild animals. While I was yet on the border, the plantation owners had to send their cotton to the border to be shipped to other parts, so it was transferred by Negro slaves as drivers. Lots of times, when these Negroes got there and took the cotton from their wagon, they would then be persuaded to go across the border by Mexicans, and then they would never return to their master. That is how lots of Negroes got to be free.

The way they used to transfer the cotton these big cotton plantations east of here they’d take it to Brownsville and put it on the wharf and ship it from there. I can remember seeing, during the cotton season, fifteen or twenty teams hauling cotton, sometimes five or six, maybe eight bales on a wagon. You see, them steamboats used to run all up and down that river. I think this cotton went out to market at New Orleans and went right out into the Gulf. Our house was a log cabin with a log chimney da’bbed with mud. The cabin was covered with grass for a roof. The fireplace was the kind of stove we had. Mother cooked in Dutch ovens. Our main meal was corn bread and milk and grits with milk. That was a little bit coarser than meal. The way we used to cook it and the best flavored is to cook it out-of-doors in a Dutch oven. We called ’em corn dodgers. Now ash cakes, you have your dough pretty stiff and smooth off a place in the ashes and lay it right on the ashes and cover it up with ashes and when it got done, you could wipe every bit of the ashes off, and get you some butter and put on it. M-m-m! I tell you, its fine! There is another way of cookin’ flour bread without a skillet or a stove, is to make up your dough stiff and roll it out thin and out it in strips and roll it on a green stick and just hold it over the coals, and it sure makes good bread. When one side cooks too fast, you can just turn it over, and have your stick long enough to keep it from burnin’ your hands. How come me to learn this was: One time we were huntin’ horse stock and there was an outfit along and the pack mule that was packed with our provisions and skillets and coffee pots and things we never did carry much stuff, not even no beddin’ the pack turned on the mule and we lost our skillet and none of us knowed it at the time. All of us was cooks, but that old Mexican that was along was the only one that knew how to cook bread that way….

WPA Slave Narrative Project, Texas Narratives, Volume 16, Part 2

Federal Writer’s Project, United States Work Projects Administration (USWPA); Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Ben Kinchlow at age 91. Born to a white slaveholding father and an enslaved woman of mixed heritage, he spent his childhood in slavery and lived in Brownsville during the Civil War. After Juneteenth, he worked as a cowboy across southern Texas.