13 José María Sánchez’s Account of the Texas Frontier

José María Sánchez, a Mexican military officer under Manuel Mier y Terán’s command, wrote his views of frontier society during his travels to the region in 1828.

Laredo, February 2. 1828-At two o’clock we continued our way through a country which was as arid as during the previous days. At daybreak we saw various herds of deer and a great number of wild horses and mares, mesteñas [mustangs], that live in these deserted regions and pasture peacefully on the immense plains. In spite of our care the water gave out because of the excessive heat and we suffered considerably from thirst. This became unbearable by twelve o’clock, and we were unable to rest as there was not a single tree under which we might stop. A plain that seemed to be on fire stretched before our eyes and our despair increased, until, at about one o’clock, we discerned in the distance the peaceful waters of the Rio Bravo del Norte [Rio Grande], whose treeless banks displayed the water lying like a silver thread upon the immense plain. The desire to reach the water made our last lap all the more arduous, and when at last the beasts, fatigued by their thirst, were scarcely able to take another step, we arrived at the coveted stream. On the banks of the river we met General Bustamante, who, with his officers, had come out to meet us. He offered me a drink of aguardiente [firewater], which I took with plenty of water, and I recovered my failing strength. It was decided to cross the river. This was accomplished with little difficulty, and at last we entered the Presidio de Laredo, situated on the opposite bank.

This village, which is one of the oldest upon the banks of the Rio Bravo, has suffered a great deal from attacks of wild Indians, principally the Lipanes, who used to lay siege to it in time of war, but now frequent it peacefully. Its population numbers about 2000 persons, all care-free people who are fond of dancing, and little inclined to work. The women, who are, as a general rule, good-looking, are ardently fond of luxury and leisure; they have rather loose ideas of morality, which cause the greater part of them to have shameful relations openly, especially with the officers, both because they are more numerous and spend their salary freely, and because they are more skillful in the art of seduction.

The garrison of the presidio consists of a company of more than one hundred men, but, in spite of this fact, the place has not prospered, nor do its inhabitants try to increase its prosperity. The streets are straight and long; all the buildings are covered with grass; and the houses have no conveniences. A desolate air envelops the entire city, and there is not a single tree to gladden the eye as the vegetation of this arid land consists of small mesquites and huisache with cactus scattered here and there. Food is extremely scarce; the little corn which is cultivated by the inhabitants is planted near the city in tracts which are over- flooded by the river in time of high water because the scarcity of rain does not permit planting it in other places. Each farmer gathers his crop, which often does not suffice his own family for half of the time between crops. Therefore the few who have beasts of burden and wish to make some profit undertake a trip to Candela or some other point and bring back corn, flour, brown sugar, and cane alcohol [vino mezcal], all of which they sell at very high prices. Often these goods cannot be secured at any price. Beef, which is the only kind of meat I have seen here, is secured with great difficulty, because the animals must be brought from long distances, often at the risk of life from attack by wild Indians. Having to undertake the trip to San Antonio [de] Bejar through uninhabited country, I had to order for our entire company what they call bastimento [provisions] in this part of the country. This consists of a sort of corn cakes resembling corn bread; toasted and ground corn with brown sugar, anis seed, or cinnamon, called pinole, which is used to make mush or may be taken with water during the hot part of the day; and dry beef, salted to keep it from spoling.

Bejar (San Antonio), March 1st. The character of the people is carefree, they are enthusiastic dancers, very fond of luxury, and the worst punishment that can be inflicted upon them is work. Doubtless, there are some individuals, out of the 1,425 that make up the total population, who are free from these failings, but they are very few. The temples and old mission buildings that constituted the missions of Concepci6n, San José, San Juan, and La Espada, are within a few leagues of the city. These, with the exception of that of San José, founded in 1720 by Fray Antonio Margil, were first established on the frontier of Texas and were moved to the San Antonio River in 1730, when San Fernando de Bejar was founded. The missionaries undertook the reduction of the gentiles with their accustomed zeal, but in our day the glamor of learning has come upon us so suddenly that it has blinded some of the very few persons of judgment [in Bejar], property owners in the main, who clamored loudly: “Out with the friars, out with the good-for-nothings.” Thus they abolished the missions and divided among themselves the lands they have not known how to cultivate and which they have left in a sad state of neglect.

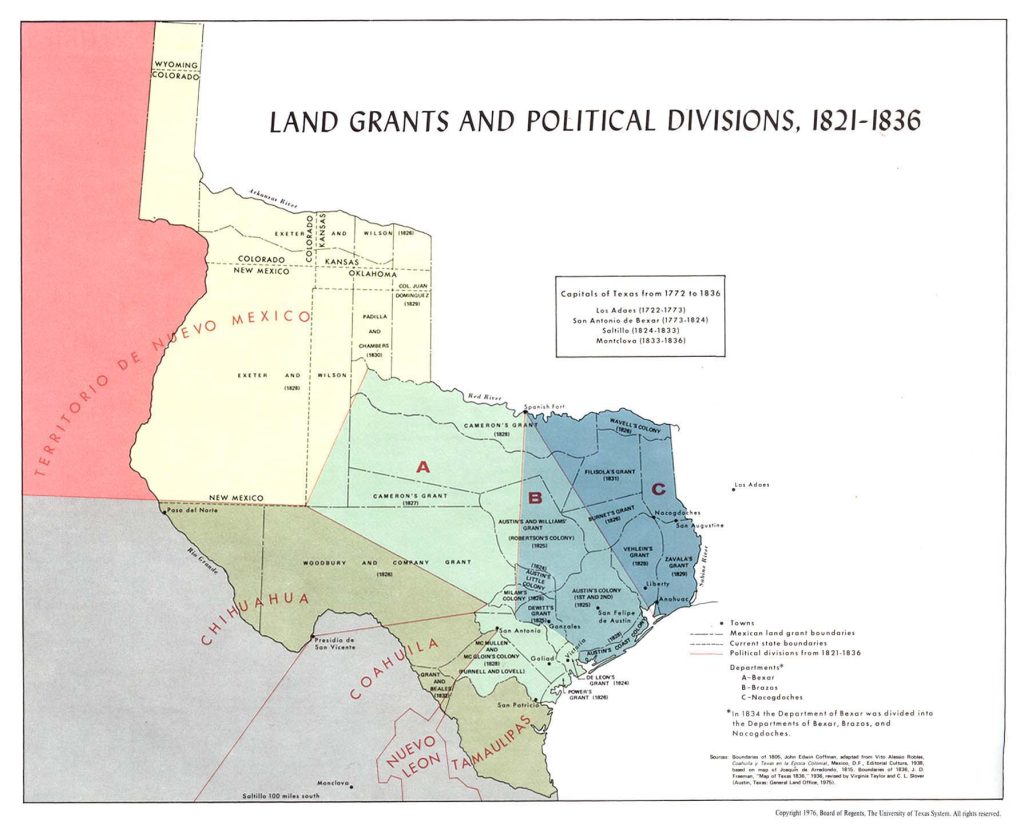

The Americans from the north have taken possession of practically all the eastern part of Texas, in most cases without the permission of the authorities. They immigrate constantly, finding no one to prevent them, and take possession of the sitio [location] that best suits them without either asking leave or going through any formality other than that of building their homes. Thus the majority of inhabitants in the Department [of Texas] are North Americans, the Mexican population being reduced to only Bejar, Nacogdoches, and La Bahia del Espiritu Santo, wretched settlements that between them do not number three thousand inhabitants, and the new village of Guadalupe Victoria that has scarcely more than seventy settlers. The government of the state, with its seat at Saltillo, that should watch over the preservation of its most precious and interesting department, taking measures to prevent its being stolen by foreign hands, is the one that knows the least not only about actual conditions, but even about its territory.

Villa de Austin [San Felipe de Austin], April 27.-We continued along hills without trees, the ground being wet and muddy, until we arrived at a distance of four or five leagues from the settlement of San Felipe de Austin, where we were met by Samuel Williams, secretary of the empresario, Mr. Stephen Austin; and we were given lodging in a house that had been prepared for the purpose. This village has been settled by Mr. Stephen Austin, a native of the United States of the North. It consists, at present, of forty or fifty wooden houses on the western bank of the large river known as Rio de los Brazos de Dios, but the houses are not arranged systematically so as to form streets; but on the contrary, lie in an irregular and desultory manner. Its population is nearly two hundred persons, of which only ten are Mexicans, for the balance are all Americans from the North with an occasional European. Two wretched little stores supply the inhabitants of the colony: one sells only whiskey, rum, sugar, and coffee; the other, rice, flour, lard, and cheap cloth. It may seem that these items are too few for the needs of the inhabitants, but they are not because the Americans from the North, at least the greater part of those I have seen, eat only salted meat, bread made by themselves out of corn meal, coffee, and home-made cheese. To these the greater part of those who live in the village add strong liquor, for they are in general, in my opinion, lazy people of vicious character. Some of them cultivate their small farms by planting corn; but this task they usually entrust to their negro slaves, whom they treat with considerable harshness.

Beyond the village in an immense stretch of land formed by rolling hills are scattered the families brought by Stephen Austin, which today number more than two thousand persons. The diplomatic policy of this empresario, evident in all his actions, has, as one may say, lulled the authorities into a sense of security, while he works diligently for his own ends. In my judgment, the spark that will start the conflagration that will deprive us of Texas, will start from this colony. All because the government does not take vigorous measures to prevent it. Perhaps it does not realize the value of what it is about to lose.

June 2.-After the rays of the sun had found their way through the thick woods of Texas, we started again, and after crossing the Neches, whose flood waters were beginning to subside, we traveled over wooded and rolling country, troubled by the mosquitoes and a burning thirst occasioned by the excessive heat. We came across a poor house occupied by two children, ten or eleven years old, pale and dirty, signs that plainly indicated the poverty of this family of solitary Americans. We heard that the mother was in Nacogdoches. How strange are these people from the North! We halted at about three in the afternoon on the western bank of the Angelina River at the house of a poor American who treated us with considerable courtesy, a very rare thing among individuals of his nationality.

Nacogdoches; Trinidad. June 3. The population [of Nacogdoches] does not exceed seven hundred persons, including the troops of the garrison, and all live in very good houses made of lumber, well-built and forming straight streets, which make the place more agreeable. The women do not number one hundred. The civil administration is entrusted to an Alcalde, and in his absence, to the first and second regidores, but up until now, they have been, unfortunately, extremely ignorant men more worthy of pity than of reproof. From this fact, the North American inhabitants (who are in the majority) have formed an ill opinion of the Mexicans, judging them, in their pride, incapable of understanding laws, arts, etc. They continually try to entangle the authorities in order to carry out the policy most suitable to their perverse designs.

The Mexicans that live here are very humble people, and perhaps their intentions are good, but because of their education and environment they are ignorant not only of the customs of our great cities, but even of the occurrences of our Revolution, excepting a few persons who have heard about them. Accustomed to the continued trade with the North Americans, they have adopted their customs and habits, and one may say truly that they are not Mexicans except by birth, for they even speak Spanish with marked incorrectness.

Source: José María Sánchez, “A Trip to Texas in 1828,” trans. Carlos E. Castañeda, Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 29 (1926), 260-61, 271.