5.6 Supplemental Readings

Supplemental Reading Topics

Baroque Music

The characteristics highlighted in the chart above give Baroque music its unique sound and appear in the music of Monteverdi, Pachelbel, Bach, and others. To elaborate:

- Definite and regular rhythms in the form of meter and “motor rhythm” (the constant subdivision of the beat) appear in most music. Bar lines become more prominent.

- The use of polyphony continues with more elaborate techniques of imitative polyphony used in the music of Handel and Bach.

- Homophonic (melody plus accompaniment) textures emerge including the use of basso continuo (a continuous bass line over which chords were built used to accompany a melodic line)

- Homophonic textures lead to increased use of major and minor keys and chord progressions (see chapter one)

The accompaniment of melodic lines in homophonic textures are provided by the continuo section: a sort of improvised “rhythm section” that features lutes, viola da gambas, cellos, and harpsichords. Continuo sections provide the basso continuo (continuous bass line) and are used in Baroque opera, concerti, and chamber music

Instrumental music featuring the violin family—such as suites, sonatas, and concertos emerge and grow prominent.

These compositions are longer, often with multiple movements that use defined forms having multiple sections, such as ritornello form and binary form.

Composers start to notate dynamics and often write abrupt changes between loud and softs, what are called terraced dynamics.

Genres of the Baroque Period

Much great music was composed during the Baroque period, and many of the most famous composers of the day were extremely prolific. To approach this music, we’ll break the historical era into the early period (the first seventy-five years or so) and the late period (from roughly 1675 to 1750). Both periods contain vocal music and instrumental music.

The main genres of the early Baroque vocal music are: madrigal, motet, and opera. The main genres of early Baroque instrumental music include the canzona (also known as the sonata) and suite. The main genres of the late Baroque instru- mental music are the concerto, fugue, and suite. The main genres of late Baroque vocal music are: Italian opera seria, oratorio, and the church cantata (which was rooted in the Lutheran chorale, already discussed in chapter three). Many of these genres will be discussed later in the chapter.

Solo music of the Baroque era was composed for all the different types of in- struments but with a major emphasis on violin and keyboard. The common term for a solo instrumental work is sonata. Please note that the non-keyboard solo instrument is usually accompanied by a keyboard, such as the organ, harpsichord or clavichord.

Small ensembles are basically named in regard to the number of performers in each (trio = three performers, etc.). The most common and popular small ensemble during the Baroque period was the trio sonata. These trios feature two melody instruments (usually violins) accompanied by basso continuo (considered the third single member of the trio).

The large ensembles genre can be divided into two subcategories, orchestral and vocal. The concerto was the leading form of large ensemble orchestral mu- sic. Concerto featured two voices, that of the orchestra and that of either a solo instrument or small ensemble. Throughout the piece, the two voices would play together and independently, through conversation, imitation, and in contrast with one another. A concerto that pairs the orchestra with a small ensemble is called a concerto grosso and a concert that pairs the orchestra with a solo instrument is called a solo concerto.

The two large vocal/choral genres for the Baroque period were sacred works and opera. Two forms of the sacred choral works include the oratorio and the mass. The oratorio is an opera without all the acting. Oratorios tell a story using a cast of characters who speak parts and may include recitative (speak singing) and arias (sung solos). The production is performed to the audience without the per- formers interacting. The Mass served as the core of the Catholic religious service and commemorates the Last Supper. Opera synthesizes theatrical performance and music. Opera cast members act and interact with each other. Types of vocal se- lections utilized in an opera include recitative and aria. Smaller ensembles (duets, trios etc.) and choruses are used in opera productions.

Baroque Opera

The beginning of the Baroque Period is in many ways synonymous with the birth of opera. Music drama had existed since the Middle Ages (and perhaps even earlier), but around 1600, noblemen increasingly sponsored experiments that combined singing, instrumental music, and drama in new ways. As we have seen in Chapter Three, Renaissance Humanism led to new interest in ancient Greece and Rome. Scholars as well as educated noblemen read descriptions of the emotional power of ancient dramas, such as those by Sophocles, which began and ended with choruses. One particularly active group of scholars and aristocrats interested in the ancient world was the Florentine Camerata, so called because they met in the rooms (or camerata) of a nobleman in Florence, Italy. This group, which included Vicenzo Galilei, father of Galileo Galilei, speculated that the reason for ancient drama’s being so moving was its having been entirely sung to a sort of declamatory style that was midway between speech and song. Although today we believe that actually only the choruses of ancient drama were sung, these circa 1600 beliefs led to collaborations with musicians and the development of opera.

Less than impressed by the emotional impact of the rule-driven polyphonic church music of the Renaissance, members of the Florentine Camerata argued that a simple melody supported by sparse accompaniment would be more moving. They identified a style that they called recitative, in which a single individual would sing a melody line that follows the inflections and rhythms of speech (see figure one with an excerpt of basso continuo). This individual would be accompanied by just one or two instruments: a keyboard instrument, such as a harpsichord or small organ, or a plucked string instrument, such as the lute. The accompaniment was called the basso continuo.

Basso continuo is a continuous bass line over which the harpsichord, organ, or lute added chords based on numbers or figures that appeared under the melody that functioned as the bass line, would become a defining feature of Baroque music. This system of indicating chords by numbers was called figured bass, and allowed the instrumentalist more freedom in forming the chords than had every note of the chord been notated. The flexible nature of basso continuo also under- lined its supporting nature. The singer of the recitative was given license to speed up and slow down as the words and emotions of the text might direct, with the instrumental accompaniment following along. This method created a homophonic texture, which consists of one melody line with accompaniment.

Composers of early opera combined recitatives with other musical numbers such as choruses, dances, arias, instrumental interludes, and the overture. The choruses in opera were not unlike the late Renaissance madrigals that we studied in chapter three. Operatic dance numbers used the most popular dances of the day, such as pavanes and galliards. Instrumental interludes tended to be sectional, that is, having different sections that sometimes repeated, as we find in other instrumental music of the time. Operas began with an instrumental piece called the Overture.

Like recitatives, arias were homophonic compositions featuring a solo singer over accompaniment. Arias, however, were less improvisatory. The melodies sung in arias almost always conformed to a musical meter, such as duple or triple, and unfolded in phrases of similar lengths. As the century progressed, these melodies became increasingly difficult or virtuosic. If the purpose of the recitative was to convey emotions through a simple melodic line, then the purpose of the aria was increasingly to impress the audience with the skills of the singer.

Opera was initially commissioned by Italian noblemen, often for important occasions such as marriages or births, and performed in the halls of their castles and palaces. By the mid to late seventeenth century, opera had spread not only to the courts of France, Germany, and England, but also to the general public, with performances in public opera houses first in Italy and later elsewhere on the continent and in the British Isles. By the eighteenth century, opera would become almost as ubiquitous as movies are for us today. Most Baroque operas featured topics from the ancient world or mythology, in which humans struggled with fate and in which the heroic actions of nobles and mythological heroes were supplemented by the righteous judgments of the gods. Perhaps because of the cosmic reaches of its narratives, opera came to be called opera seria, or serious opera. Librettos, or the words of the opera, were to be of the highest literary quality and designed to be set to music. Italian remained the most common language of opera, and Italian opera was popular in England and Germany; the French were the first to perform operas in their native tongue.

Rise of the Orchestra and the Concerto

The Baroque period also saw the birth of the orchestra, which was initially used to accompany court spectacle and opera. In addition to providing accompaniment to the singers, the orchestra provided instrumental only selections during such events. These selections came to include the overture at the beginning, the interludes between scenes and during scenery changes, and accompaniments for dance sequences. Other predecessors of the orchestra included the string bands employed by absolute monarchs in France and England and the town collegium musicum of some German municipalities. By the end of the Baroque period, com- posers were writing compositions that might be played by orchestras in concerts, such as concertos and orchestral suites.

The makeup of the Baroque orchestra varied in number and quality much more than the orchestra has varied since the nineteenth century; in general, it was a small- er ensemble than the later orchestra. At its core was the violin family, with woodwind instruments such as the flute, recorder, and oboe, and brass instruments, such as the trumpet or horn, and the timpani for percussion filling out the texture. The Baroque orchestra was almost always accompanied by harpsichord, which together with the one or more of the cellos or a bassonist, provided a basso continuo. The new instruments of the violin family provided the backbone for the Baroque orchestra. The violin family—the violin, viola, cello (long form violoncello) and bass violin—were not the first bowed string instruments in Western classical music. Bowed strings attained a new prominence in the seventeenth century with the widespread and increased manufacturing of violins, violas, cellos, and basses. With the popularity of the violin family, instruments of the viola da gamba family fell to the side- lines. Composers started writing compositions specifically for the members of the violin family, often arranged with two groups of violins, one group of violas, and a group of cellos and double basses, who sometimes played the same bass line as played by the harpsichord.

One of the first important forms of this instrumental music was the concerto. The word concerto comes from the Latin and Italian root concertare, which has connotations of both competition and cooperation. The musical concerto might be thought to reflect both meanings.

A concerto is a composition for an instrumental soloist or soloists and orchestra; in a sense, it brings together these two forces in concert; in another sense, these two forces compete for the attention of the audience. Concertos are most often in three movements that follow a tempo pattern of fast – slow – fast. Most first movements of concertos are in what has come to be called ritornello form. As its name suggests, a ritornello is a returning or refrain, played by the full orchestral ensemble. In a concerto, the ritornello alternates with the solo sections that are played by the soloist or soloists.

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) began studying for the priesthood at age fifteen and, once ordained at age twenty-five, received the nickname of “The Red Priest” because of his hair color. He worked in a variety of locations around Europe, including at a prominent Venetian orphanage called the Opsedale della Pietà. There he taught music to girls, some of whom were illegitimate daughters of prominent noblemen and church officials from Venice. This orphanage became famous for the quality of music performed by its in- habitants. Northern Europeans, who would travel to Italy during the winter months on what they called “The Italian Tour”—to avoid the cold and rainy weather of cities such as Paris, Berlin, and London—wrote home about the fine performances put on by these orphans in Sunday afternoon concerts. These girls performed concertos such as Vivaldi’s well known Four Seasons. The Four Seasons refers to a set of four concertos, each of which is named after one of the seasons. As such, it is an example of program music, a type of music that would become more prominent in the Baroque period. Program music is instrumental music that represents something extra musical, such as the words of a poem or narrative or the sense of a painting or idea. A composer might ask orchestral instruments to imitate the sounds of natural phenomenon, such as a babbling brook or the cries of birds. Most program music carries a descriptive title that suggests what an audience member might listen for. In the case of the Four Seasons, Vivaldi connected each concerto to an Italian sonnet, that is, to a poem that was descriptive of the season to which the concerto referred. Thus in the case of Spring, the first concerto of the series, you can listen for the “festive song” of birds, “murmuring streams,” “breezes,” and “lightning and thunder.”

Each of the concertos in the Four Seasons has three movements, organized in a fast – slow – fast succession. We’ll listen to the first fast movement of Spring. Its “Allegro” subtitle is an Italian tempo marking that indicates music that is fast. As a first movement, it is in ritornello form. The movement opens with the ritornello, in which the orchestra presents the opening theme. This theme consists of motives, small groupings of notes and rhythms that are often repeated in sequence. This ritornello might be thought to reflect the opening line from the son- net. After the ritornello, the soloist plays with the accompaniment of only a few instruments, that is, the basso continuo. The soloist’s music uses some of the same motives found in the ritornello but plays them in a more virtuosic way, showing off one might say.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/zW0pEIymWK8?si=oYLLZHKy5R94hQAx

- Composer: Antonio Vivaldi

- Composition:The first movement of Spring from The Four Seasons

- Date: 1720s

- Genre: solo concerot and program music

- Form: ritornello form

- Nature of text: the concerto is accompanied by an Italian sonnet about springtime. The first five line are associated with the first movement:Springtime is upon us.

The birds celebrate her return with festive song,

and murmuring streams are softly caressed by the breezes.

Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar, casting their dark mantle over heaven, Then they die away to silence, and the birds take up their charming songs once more. - Performing forces: solo violin and string orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is the first movement of a solo concerto that uses ritornello form

- This is program music

- It uses terraced dynamics

- It uses a fast allegro tempo

- The orchestral ritornellos alternate with the sections for solo violin

- Virtuoso solo violin lines

- Motor rhythm

- Melodic themes composed of motives that spin out in sequences

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) was one of the superstars of the late Baroque period He was born the same year as one of our other Baroque superstars, Johann Sebastian Bach, not more than 150 miles away in Halle, Germany. His father was an attorney and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, but Handel decided that he wanted to be a musician instead. With the help of a local nobleman, he persuaded his father to agree. After learning the basics of composition, Handel journeyed to Italy to learn to write opera. Italy, after all, was the home of opera, and opera was the most popular musical entertainment of the day. After writing a few operas, he took a job in London, England, where Italian opera was very much the rage, eventually establishing his own opera company and producing scores of Italian operas, which were initially very well received by the English public. After a decade or so, however, Italian opera in England imploded. Several opera companies there each

competed for the public’s business. The divas who sang the main roles and whom the public bought their tickets to see demanded high salaries. In 1728, a librettist name John Gay and a composer named Johann Pepusch premiered a new sort of opera in London called ballad opera. It was sung entirely in English and its music was based on folk tunes known by most inhabitants of the British Isles. For the English public, the majority of whom had been attending Italian opera without understanding the language in which it was sung, English language opera was a big hit. Both Handel’s opera company and his competitors fought for financial stability, and Handel had to find other ways to make a profit. He hit on the idea of writing English oratorio.

Oratorio is sacred opera that is not staged. Like operas, they are relatively long works, often spanning over two hours when performed in entirety. Like op- era, oratorios are entirely sung to orchestral accompaniment. They feature recitatives, arias, and choruses, just like opera. Most oratorios also tell the story of an important character from the Christian Bible. But oratorios are not acted out. Historically-speaking, this is the reason that they exist. During the Baroque period at sacred times in the Christian church year such as Lent, stage entertainment was prohibited. The idea was that during Lent, individuals should be looking inward and preparing themselves for the death and resurrection of Christ, and attending plays and operas would distract from that. Nevertheless, individuals still wanted entertainment, hence, oratorios. These oratorios would be performed as concerts not in the church but because they were not acted out, they were perceived as not having a “detrimental” effect on the spiritual lives of those in the audience. The first oratorios were performed in Italy; then they spread elsewhere on the continent and to England.

Handel realized how powerful ballad opera, sung in English, had been for the general population and started writing oratorios but in the English language. He used the same music styles as he had in his operas, only including more choruses. In no time at all, his oratorios were being lauded as some of the most popular performances in London.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/GDEi38TxBME?si=EB8Bc5e8bNzaQWvh

- Composer: George Frideric Handel

- Composition: “Comfort Ye” and “Every Valley” from Messiah

- Date: 1741

- Genre: accompanied recitative and aria from an oratorio

- Form: accompanied recitative—through composed; aria—binary form AA’

- Nature of text: English language libretto quoting the Bible

- Performing forces:

solo

tenor and orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- As an oratorio, it uses the same styles and forms as operas but is not staged

- The aria is very virtuoso with its melismas, and alternates between orchestral ritornellos and solo sections.

- The accompanied recitative uses more instruments than standard basso continuo-accompanied recitative, but the vocal line retains the flexibility of recitative

- Motor rhythm in the aria

- In a major key

- In the aria, the second solo section is more ornamented than the first, as was often the custom

Johann Sebastian Bach (B. 1685-1750) During the seventeenth century, many families passed their trades down to the next generation so that future gen- erations may continue to succeed in a vocation. This practice also held true for Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach was born into one of the largest musical families in Eisenach of the central Germany region known as Thuringia. He was orphaned at the young age of ten and raised by an older brother in Ohrdruf, Germany. Bach’s older brother was a church organist who pre- pared the young Johann for the family vocation. The Bach family, though great in number, were mostly of the lower musical stature of town’s musicians and/or Lutheran Church organist. Only a few of the Bach’s had achieved the accomplished stature of court musicians, but the Bach family members were known and respected in the region. Bach also in turn taught four of his sons who later became leading composers for the next generation.

At the age of thirty-eight, Bach assumed the position as cantor of the St. Thom- as Lutheran Church in Leipzig, Germany. Several other candidates were considered for the Leipzig post, including the famous composer Telemann who refused the offer. Some on the town council felt that, since the most qualified candidates did not accept the offer, the less talented applicant would have to be hired. It was in this negative working atmosphere that Leipzig hired its greatest cantor and musician. Bach worked in Leipzig for twenty-seven years (1723-1750).

Leipzig served as a hub of Lutheran church music for Germany. Not only did Bach have to compose and perform, he also had to administer and organize

Bach’s A Mighty Fortress is Our God cantata, like most of his cantatas, has several movements. It opens with a polyphonic chorus that presents the first verse of the hymn. After several other movements (including recitatives, arias, and du- ets), the cantata closes with the final verse of the hymn arranged for four parts.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/fAt2LgpDnaA?si=ocLJOIupDcW5m2ql

- Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

- Composition: Ein Fest Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress Is Out God) Cantata 80

- Date: 1717-1740

- Genre: first-movement polyphonic chorus and final movement chorale from a church cantata

- Form: sectional, divided by statements of Luther’s original melody line in sustained notes in the trumpets, oboes, and cellos.

- Nature of text: See lyrics above from Martin Luther’s original hymn.

- Performing forces: solo violin and string orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- This is representative of Bach’s mastery of taking a Martin Luther hymn and arranging it in imitative polyphony for all four voice parts and instrumental part

- Bach weaves new melody lines into a beautiful polyphonic choral work

- Most of the time the instruments double (or play the same music as) the four voice parts.

- He also has the trumpets, oboes, and cellos divide up Luther’s exact melody into nine phrases. They present the first phrase after the first section of the chorus and then subsequent phrases throughout the chorus. When they play the original melody, they do so in canon: the trumpets and oboes begin and then the cellos enter after about a measure.

- Also listen to see if you can hear the augmentation in the work. The original tune is performed in this order of the voices: Tenors, Sopranos, Tenors, Sopranos, Basses, Altos, Tenors, Sopranos, and then the Tenors

Eastern Asia

Kabuki and Bunraku

Video URL: https://youtu.be/oc3dWwbctw4?si=1TdkUSdw3WRZTG_r

Copyright: Crash Course 2024

Kabuki Prints

Kabuki theatre developed from a popular entertainment performed by female dancers in Kyoto. This was banned in 1629 as detrimental to public morals and replaced by young men’s Kabuki. From 1652 this was replaced by Kabuki performed by adult males. Although the government attempted to regulate Kabuki, the theatres, and their neighboring teahouses and houses of often homosexual assignation became thriving centers of urban culture, part of the ‘floating world’. The leading actors, including the onnagata, male performers of female roles, influenced fashion and taste and quickly became the subject of popular woodblock prints. It is likely that between one third and a half of prints published in the Edo period depicted Kabuki actors.

Three schools of artists specialized in designing actor prints. In the first half of the eighteenth century the Torii school was prominent. They started out using an exaggerated, muscular drawing style which captured the action of the animated aragoto (‘rough stuff’) style of the Kabuki. Later the Torii were eclipsed by the Katsukawa school. The founder, Shunshō and his contemporary Bunchō, were more restrained, and concentrated on capturing the likenesses of the actors (nigao-e). The Katsukawa school gave way to the Utagawa school (Toyokuni and Kunisada) from the 1790s onwards, and a return to a more florid schematic style. In addition, the enigmatic Tōshūsai Sharaku appeared briefly like a passing comet in 1794–95. In 1794 he produced a unique group of almost thirty highly individualized portraits in the ōkubi-e (‘big head’) format. These exaggerate the expressive quirks and gestures of the leading actors of his day.

It is often possible to date actor prints by referring to surviving printed banzuke (playbills) and yakusha hyōbanki (actor critiques). This is useful when studying the chronological development of an Ukiyo-e artist’s style.

‘Gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines’

The Kabuki ‘armor-tugging’ scene originated in the play about the revenge of the Soga brothers. It involved a struggle between the characters Soga no Gorō (right) and Kobayashi Asahina (left). However, it came to be inserted into other unrelated plays and in the summer of 1717 it was due to be performed ‘underwater’ in the play ‘The Battle of Coxinga’ (Kokusenya gassen), at the Ichimura Theatre. A large signboard was painted to hang outside the theatre, showing Hiroji bursting out through the side of the boat to grasp Danzō’s armor. In the event, the scene was cancelled, but the signboard painting, now lost, may well have been the inspiration for this print, since the Torii artists were responsible for producing all of the signboards, prints and illustrated programmes for the Kabuki theatres in Edo.

The characteristic acting style of Edo was known as aragoto (‘rough stuff’). The lively drawing style of the early Torii artists admirably catches the boisterous energy of the action. A later Japanese critic describes their figures as typically having ‘gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines’. The impact of this print is increased by the application by hand of orange lead pigment (tan).

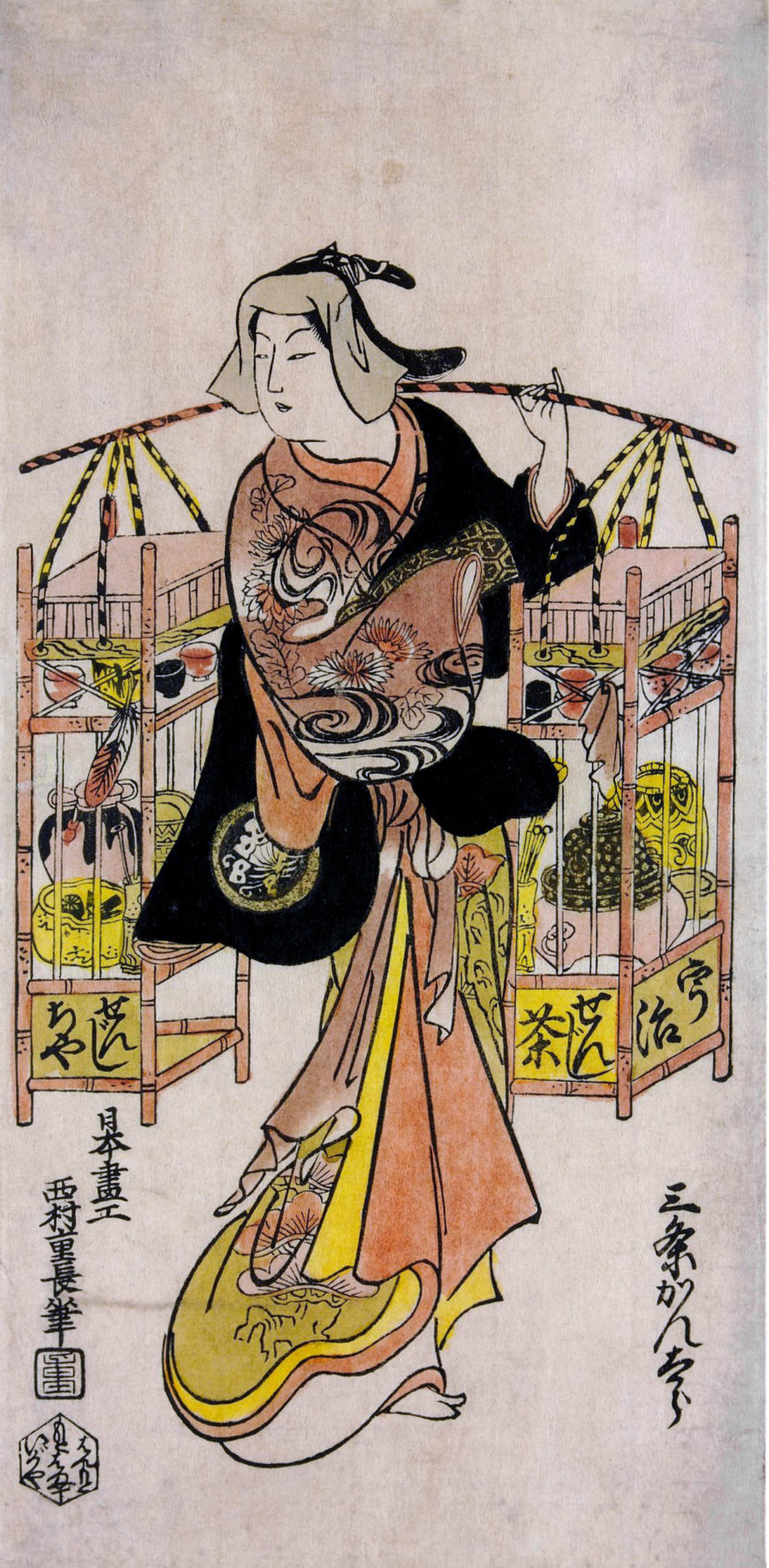

Nishimura Shigenaga, The actor Sanjō Kantarō as a tea-seller, c. 1716–36 (Edo period), Edo, Japan, a woodblock print, 32.8 x 15.9 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Female Impersonators

The onnagata (female impersonator) Sanjō Kantarō plays the Kabuki role of a seller of Uji tea carrying her portable stall. The print is hand-colored in shades of red, pink and purple, all now somewhat faded. Glossy glue has been applied to the black over-kimono to give the effect of lacquer and there are sprinklings of brass dust on the obi sash, the butterfly crest on the sleeve and the lid of the kettle.

Kantarō has slipped off the right sleeve of the over-kimono to show off the elaborate under-kimono patterned with designs of waves and chrysanthemums. The overall elegance of the figure, especially the cocked little finger, suggests the he may be playing the role of some famous beauty in humble disguise. The tea implements are also drawn with great care, and we can see clearly all the details of the brazier and kettle with bamboo tea-scoop, tea jar, water pot and small cups.

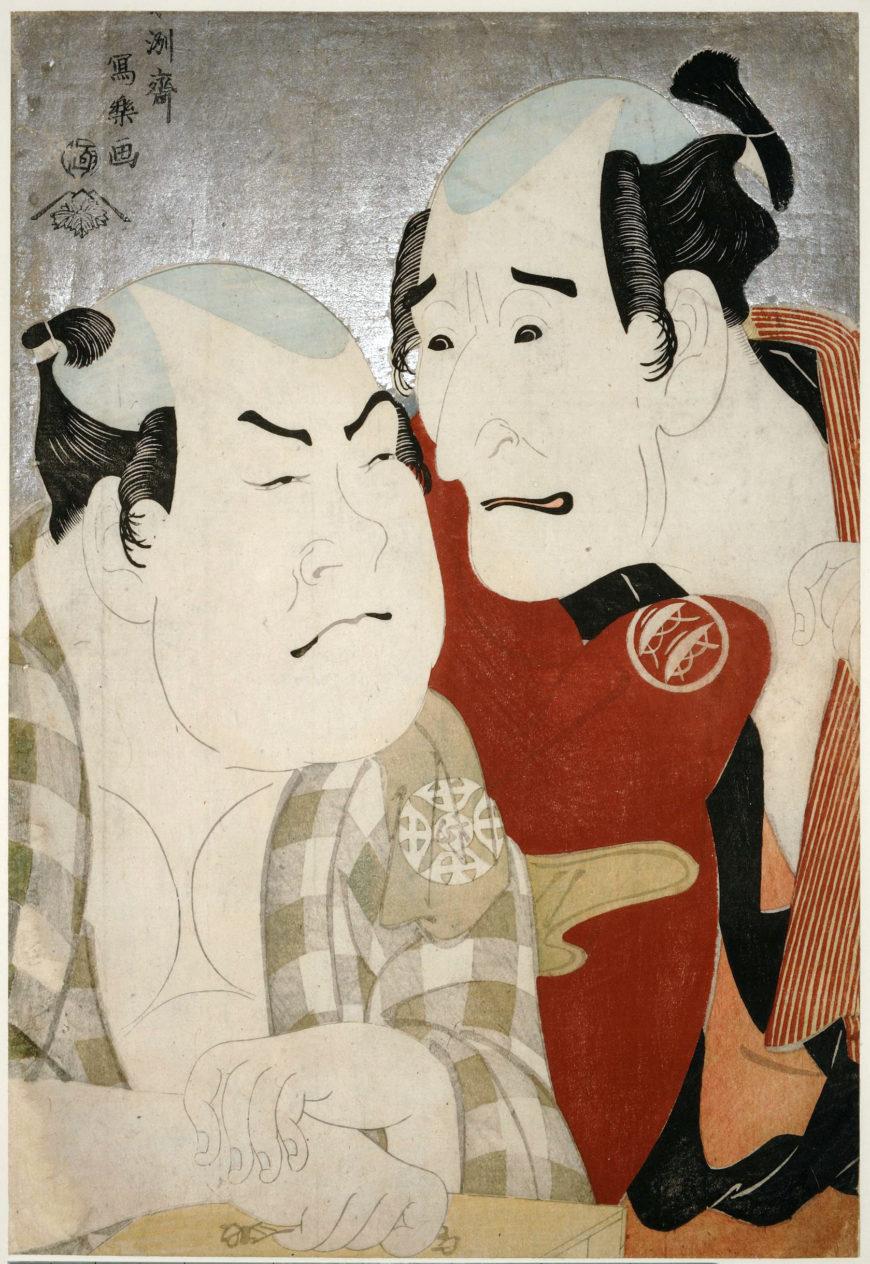

Tōshūsai Sharaku, The Actors Nakamura Wadaemon and Nakamura Konozō, 1794 (Edo period), woodblock print, Japan, 35 x 24.2 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Large Head Portraits

The artist Tōshūsai Sharaku worked for a only a brief period, for ten months between 1794 and 1795. Very little is known of him before or after this period and his identity is the object of much conjecture among historians of Japanese art. The most likely theory is that he was one Saitō Jūrobei originally a nō actor in the service of the Lord of Awa.

Sharaku had a special talent for characterizing his subjects by differentiating their facial features. Furthermore, the development of the okubi-e (‘large head’ portraits) in the mid-1790s encouraged a more penetrating analysis of character. This print shows a scene from the play ‘A Medley of Tales of Revenge’ (Katakiuchi noriai-banashi) performed at the Kiri Theatre in the fifth month of 1794. The two subjects are strongly contrasted. On the right, Wadaemon in the role of Bodara no Chōzaemon, a customer visiting a house of pleasure, with his sharp, angular features, pleads with Kanagawaya Gon, the chubby boatman, played by Konozō. The boatman’s narrowed eyes and snub nose suggest that he is bent on striking a hard bargain.

‘Wait a moment!’

Kunimasa (1773–1810) designed this print as a tribute to the great Ebizō (formerly Ichikawa Danjūrō V) on the occasion of his retirement from the Kabuki stage in 1796. He chose to depict him in the shibaraku scene, one of the most famous in all Kabuki drama. With a thundering cry of ‘shibaraku!‘ (‘wait a moment!’), the hero bursts on to the hanamichi walkway from the back of the theatre just in time to save the characters on stage from certain death. Perhaps, in this print, Ebizō is depicted on the very brink of calling out.

In this okubi-e (‘large-head portrait’), Kunimasa gives us an unusual profile view of Ebizō. The main elements of the striking costume and make-up are clearly visible: the ‘five-spoke wheel’ wig with, top right, the paper ‘strength’ decorations under the black lacquer court hat; the fierce red make-up; the green jacket with design of stylized cranes; and most significant of all, the familiar persimmon-colored costume with the three white interlocking squares (mimasu), which are the Ichikawa family emblem.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, A farewell surimono for Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII, 1849 (Edo period), Japan, color woodblock print, 27.2 x 55.5 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Tribute to a Kabuki actor

This print marks the occasion of the actor Danjūrō VIII’s temporary departure from the Edo stage in 1849 when he travelled to Osaka to visit his father, Danjūrō VII, who had been sent into exile there some seven years earlier under the severe Tempō Reforms.

To honor their idol, Danjūrō VIII, members of two haiku poetry clubs—the Shimba and the Uogashi clubs located in the fish market districts of Edo—banded together and commissioned the large de-luxe-edition print from Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). He chose as his subject a monster carp kite, appropriate to his sponsors and also to the time of year: Boys’ Day Festival is celebrated on the 5th day of the 5th month, when giant carp streamers are flown from poles. A carp ascending a waterfall was also one crest used by the Danjūrō lineage of actors. The design includes a cloth banner painted with a portrait of Shōki, ancient Chinese queller of demons. As a further tribute to the Danjūrō line, Shōki is given the features of the father, while the leaping carp, representing perseverance, may symbolize the son.

Copyright: The British Museum, “Kabuki actor prints,” in Smarthistory, March 4, 2021, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/kabuki-actor-prints/.