3.4 Supplemental Readings

Supplemental Readings

Roman Poetry

Read an English translation of “The Metamorphoses of Ovid” from Project Gutenberg

Imperial Roman Architecture

Column of Trajan

Video URL: https://youtu.be/to3kP7U3PoM?si=TLeQM_ILqZlg_QpC

The Colosseum

Video URL: https://youtu.be/7FpQ1CmcPYQ?si=T2SK9aZxmjIiBlhE

The Arch of Titus

Video URL: https://youtu.be/2Pz_p8Tf24g?si=Lu3nlSiNKYG7WmQf

Hadrian’s Villa

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Nu_6X04EGHk?si=4_Qtxg5F4nQFta8t

Roman Theater

Video from Crash Course URL: https://youtu.be/jQpvph777Pg?si=R0dTldw67cyQ-Vj-

Read an English translation of “The Two Tragedies of Seneca: Medea and The Daughters of Troy” from Project Gutenberg

Republican and Imperial Sculpture

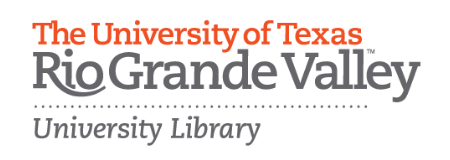

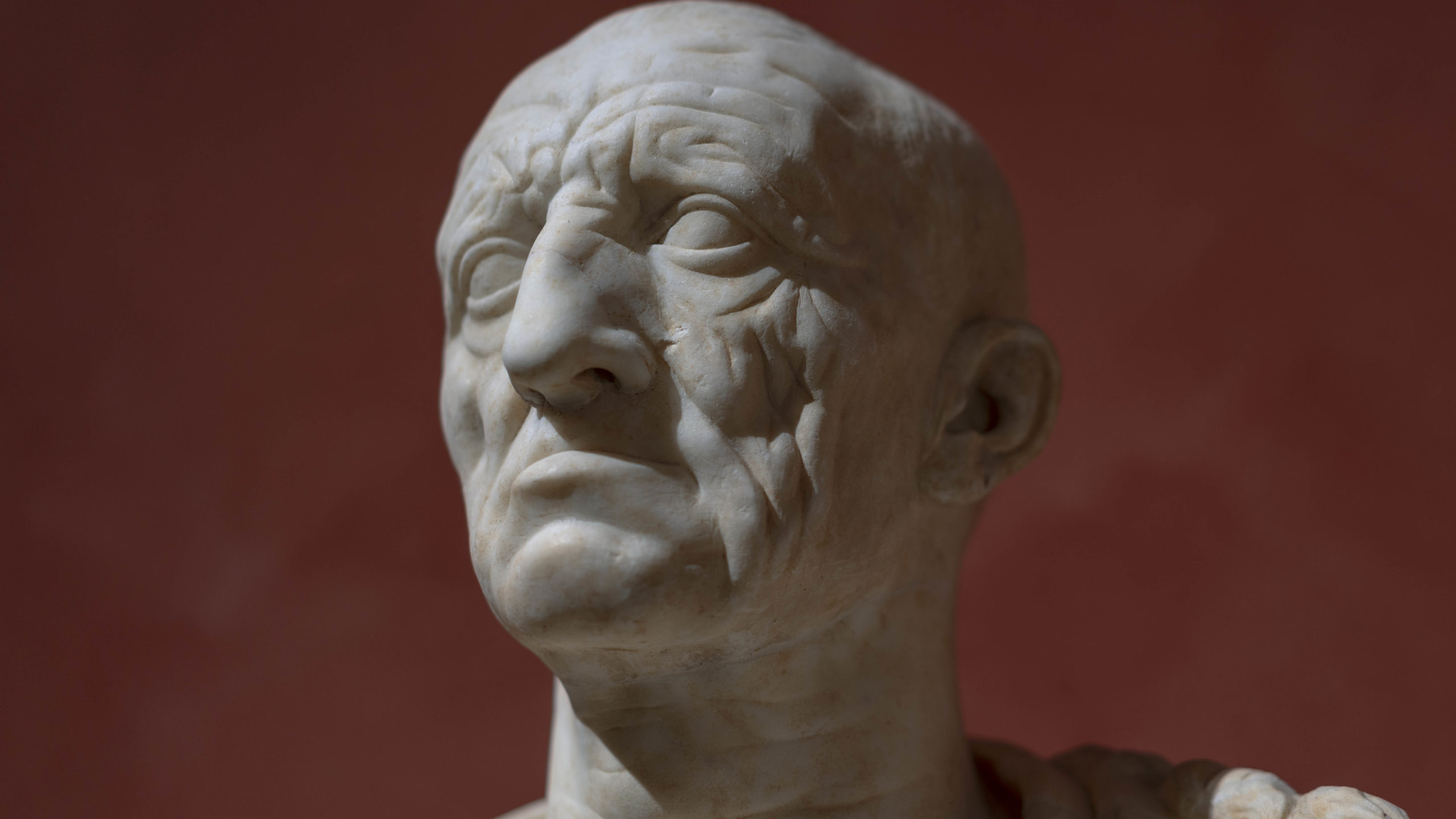

Head of a Roman Patrician

The Portrait

This portrait head, now housed in the Palazzo Torlonia in Rome, Italy, comes from Otricoli (ancient Ocriculum) and dates to the middle of the first century B.C.E. The name of the individual depicted is now unknown, but the portrait is a powerful representation of a male aristocrat with a hooked nose and strong cheekbones. The figure is frontal without any hint of dynamism or emotion—this sets the portrait apart from some of its near contemporaries. The portrait head is characterized by deep wrinkles, a furrowed brow, and generally an appearance of sagging, sunken skin—all indicative of the veristic style of Roman portraiture.

Verism

Verism can be defined as a sort of hyperrealism in sculpture where the naturally occurring features of the subject are exaggerated, often to the point of absurdity. In the case of Roman Republican portraiture, middle age males adopt veristic tendencies in their portraiture to such an extent that they appear to be extremely aged and care worn. This stylistic tendency is influenced both by the tradition of ancestral imagines as well as a deep-seated respect for family, tradition, and ancestry. The imagines were essentially death masks of notable ancestors that were kept and displayed by the family. In the case of aristocratic families these wax masks were used at subsequent funerals so that an actor might portray the deceased ancestors in a sort of familial parade (Polybius History 6.53.54). The ancestor cult, in turn, influenced a deep connection to family. For Late Republican politicians without any famous ancestors (a group famously known as ‘new men’ or ‘homines novi’) the need was even more acute—and verism rode to the rescue. The adoption of such an austere and wizened visage was a tactic to lend familial gravitas to families who had none—and thus (hopefully) increase the chances of the aristocrat’s success in both politics and business. This jockeying for position very much characterized the scene at Rome in the waning days of the Roman Republic and the Otricoli head is a reminder that one’s public image played a major role in what was a turbulent time in Roman history.

Copyright: Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Head of a Roman Patrician,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed April 9, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/head-of-a-roman-patrician/.

Augustus and the Power of Images

Today, politicians think very carefully about how they will be photographed. Think about all the campaign commercials and print ads we are bombarded with every election season. These images tell us a lot about the candidate, including what they stand for and what agendas they are promoting. Similarly, Roman art was closely intertwined with politics and propaganda. This is especially true with portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire; Augustus invoked the power of imagery to communicate his ideology.

Augustus of Primaporta

One of Augustus’ most famous portraits is the so-called Augustus of Primaporta of 20 B.C.E. (the sculpture gets its name from the town in Italy where it was found in 1863). At first glance this statue might appear to simply resemble a portrait of Augustus as an orator and general, but this sculpture also communicates a good deal about the emperor’s power and ideology. In fact, in this portrait Augustus shows himself as a great military victor and a staunch supporter of Roman religion. The statue also foretells the 200 year period of peace that Augustus initiated, called the Pax Romana.

In this marble freestanding sculpture, Augustus stands in a contrapposto pose (a relaxed pose where one leg bears weight). The emperor wears military regalia and his right arm is outstretched, demonstrating that the emperor is addressing his troops. We immediately sense the emperor’s power as the leader of the army and a military conqueror.

Delving further into the composition of the Primaporta statue, a distinct resemblance to Polykleitos’ Doryphoros, a Classical Greek sculpture of the fifth century B.C.E., is apparent. Both have a similar contrapposto stance and both are idealized. That is to say that both Augustus and the Spear-Bearer are portrayed as youthful and flawless individuals: they are perfect. The Romans often modeled their art on Greek predecessors. This is significant because Augustus is essentially depicting himself with the perfect body of a Greek athlete: he is youthful and virile, despite the fact that he was middle-aged at the time of the sculpture’s commissioning. Furthermore, by modeling the Primaporta statue on such an iconic Greek sculpture created during the height of Athens’ influence and power, Augustus connects himself to the Golden Age of that previous civilization.

The Cupid and Dolphin

So far the message of the Augustus of Primaporta is clear: he is an excellent orator and military victor with the youthful and perfect body of a Greek athlete. Is that all there is to this sculpture? Definitely not! The sculpture contains even more symbolism. First, at Augustus’ right leg is cupid figure riding a dolphin. The dolphin became a symbol of Augustus’ great naval victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, a conquest that made Augustus the sole ruler of the Empire. The cupid astride the dolphin sends another message too: that Augustus is descended from the gods. Cupid is the son of Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Julius Caesar, the adoptive father of Augustus, claimed to be descended from Venus and therefore Augustus also shared this connection to the gods.

The Breastplate

Finally, Augustus is wearing a cuirass, or breastplate, that is covered with figures that communicate additional propagandistic messages. Scholars debate over the identification over each of these figures, but the basic meaning is clear: Augustus has the gods on his side, he is an international military victor, and he is the bringer of the Pax Romana, a peace that encompasses all the lands of the Roman Empire.

Surrounding this central zone are gods and personifications. At the top are Sol and Caelus, the sun and sky gods respectively. On the sides of the breastplate are female personifications of countries conquered by Augustus. These gods and personifications refer to the Pax Romana. The message is that the sun is going to shine on all regions of the Roman Empire, bringing peace and prosperity to all citizens. And of course, Augustus is the one who is responsible for this abundance throughout the Empire.

Beneath the female personifications are Apollo and Diana, two major deities in the Roman pantheon; clearly Augustus is favored by these important deities and their appearance here demonstrates that the emperor supports traditional Roman religion. At the very bottom of the cuirass is Tellus, the earth goddess, who cradles two babies and holds a cornucopia. Tellus is an additional allusion to the Pax Romana as she is a symbol of fertility with her healthy babies and overflowing horn of plenty.

Not Simply a Portrait

The Augustus of Primaporta is one of the ways that the ancients used art for propagandistic purposes. Overall, this statue is not simply a portrait of the emperor, it expresses Augustus’ connection to the past, his role as a military victor, his connection to the gods, and his role as the bringer of the Roman Peace.

Copyright: Julia Fischer, “Augustus of Primaporta,” in Smarthistory, November 6, 2020, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/augustus-of-primaporta/.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/MuD06cnjtAM?si=hbRXG7LebP6O9TEa

Copyright: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “The Colossus of Constantine,” in Smarthistory, December 9, 2015, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-colossus-of-constantine/.