1.3 Africa

Ancient Egypt and Nubia

Egypt’s impact on other cultures was undeniably immense. From the earliest periods of Predynastic Egypt, there is evidence of trade connections that extended as far east as the Indus Valley. These trade routes passed through the Near East, resulting in an early exchange of motifs and ideas between the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. The New Kingdom brought even more active connections with Western Asia, including robust commercial and diplomatic relationships as well as a mutual exchange of imagery and concepts with cultures like the Assyrians and the Hittites. Lively interactions with the south contributed to dynamic cultures, such as the Kushites, who ruled Egypt during the 25th Dynasty and whose monuments displayed an innovative blend of local Nubian and pharaonic imagery.

Rulers and the elite from Meroe, in modern Sudan, were buried in pyramid tombs for many centuries—with more than 200 having been identified, that country actually contains more pyramids within its borders than Egypt does. Egypt also provided some of the building blocks for the Aegean, Greek, and Roman cultures and, through them, influenced many aspects of Western tradition.

Today, Egyptian imagery, concepts, and perspectives are found everywhere; when you know what to look for, you will see them in architectural forms, on money, and in our day-to-day lives. Many cosmetic surgeons, for example, use the silhouette of Queen Nefertiti (whose name means “the beautiful one has come”) in their advertisements.

Longevity

Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for more than 3,000 years and showed a stunning level of continuity. That is more than 15 times the age of the United States, and consider how often our culture shifts; as recently as 2003, there was no Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube.

While today we consider the Greco-Roman period to be in the distant past, it should be noted that Cleopatra VII’s reign is closer to our own time than it was to that of the construction of the pyramids of Giza. It took humans nearly 4,000 years to build something—anything—taller than the Great Pyramid. Contrast that span to modern times; we get excited when a record lasts longer than a decade.

Consistency and stability

Egypt’s stability is in stark contrast to the Ancient Near East of the same period, which endured an overlapping series of cultures and upheavals with amazing regularity. The earliest royal monuments, such as the Narmer Palette carved around 3100 B.C.E., display identical royal costumes and poses as those seen on later rulers, even Ptolemaic kings and Roman emperors on their temples more than three millennia later.

This consistency and stability is closely linked with one of the central foundational concepts in the way ancient Egyptians saw the world around them. In their view, creation occurred when order triumphed over chaos and harnessed that amorphous power to bring the land of Egypt into existence. The perfect cosmic balance that resulted created the consistent cycles they saw in their natural world, such as the daily rising and setting of the sun and the Nile’s annual inundation. This divine order was known as ma’at—embodying truth, righteousness, justice, and cosmic law—and was eventually personified as a goddess. There was a perpetual struggle between ma’at and the chaos, known as isfet. From early in Egypt’s history, a primary role of the pharaoh was to be the champion of ma’at and preserve that cosmic order to help protect Egypt from the isfet that surrounded them. The ongoing preservation of ma’at was seen as fundamentally important and the drive to maintain that perfect cosmic balance permeated the culture on multiple levels.

A vast amount of Egyptian imagery, especially royal imagery that was governed by decorum (a sense of what was ‘appropriate’), remained extraordinarily consistent throughout its history. This is why, especially to the untrained eye, their art appears extremely static—and in terms of symbols, gestures, and the way the body is rendered, it was. It was intentional, as the consistency was the whole point. The Egyptians were well aware of their consistency, which they viewed as stability, divine balance, and clear evidence of ma’at and the correctness of their culture.

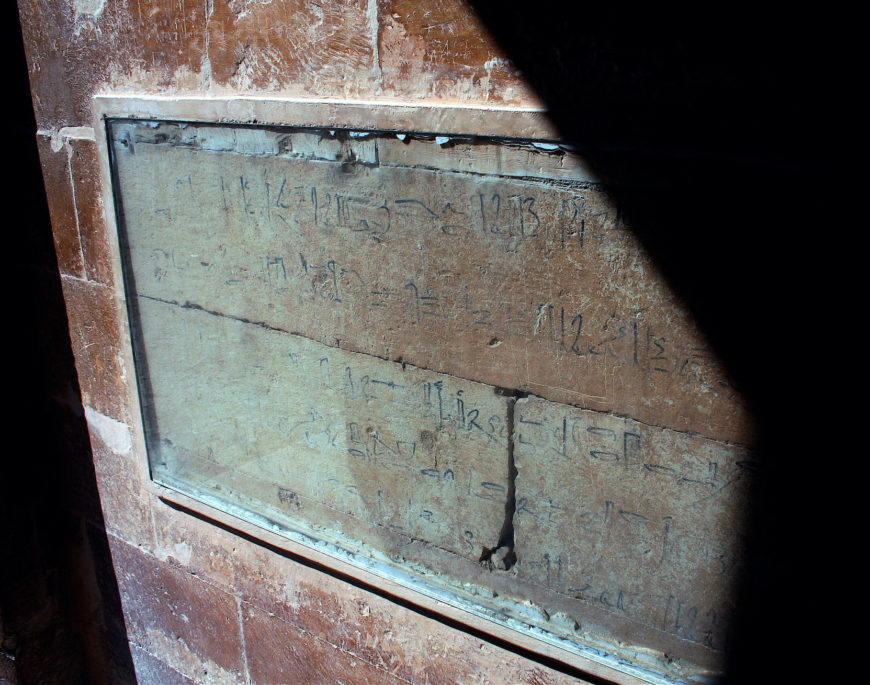

New Kingdom graffiti inside Step Pyramid complex (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

This consistency was also closely related to a fundamental belief that depictions had an impact beyond the image itself—tomb scenes of the deceased receiving food or temple scenes of the king performing perfect rituals for the gods were functionally causing those things to occur in the divine realm. If the image of the bread loaf was omitted from the deceased’s table, they had no bread in the afterlife; if the king was depicted with the incorrect ritual implement, the ritual was incorrect and could have dire consequences. This belief led to active resistance to change in codified depictions.

The earliest recorded “tourist graffiti” on the planet came from a visitor from the time of Ramses II, who left their appreciative mark at the already 1300-year-old site of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, the earliest of the massive royal stone monuments. They were understandably impressed by the works of their ancestors and wrote of their desire to continue that ancient legacy.

Geography

Egypt is a land of duality and cycles, both in topography and culture. The geography is almost entirely rugged, barren desert, except for an explosion of green that straddles either side of the Nile as it flows the length of the country. The river emerges from far to the south, deep in Africa, and empties into the Mediterranean sea in the north after spreading from a single channel into a fan-shaped system, known as a delta, in its northernmost section. The river valley is flanked by imposing cliffs of limestone and sandstone, with deposits of other, harder stones like granite and granodiorite being found in the area of Aswan to the south.

One of the reasons for the overall stability of Egyptian culture was that it was largely isolated by virtue of its geography. With high cliffs and expansive deserts bordering the east and west, the sea at the north, and a series of huge rapids in the Nile to the south (known as cataracts), the stretch of the river valley that gave rise to dynastic Egypt was quite closed off from the outside. Egypt was undoubtedly the “gift of the Nile,” as the Greek historian Herodotus famously wrote. The influence of this river on Egyptian culture and development cannot be overstated without its presence, the civilization would have been entirely different. The Nile provided not only a constant source of life-giving water, but created the fertile lands that fed the growth of this unique (and uniquely resilient) culture.

The Pharaoh—Not Just a King

Rulers in Egypt were complex intermediaries that straddled the terrestrial and divine realms. They were, obviously, living humans, but upon accession to the throne, they also embodied the eternal office of kingship itself. The ka, or spirit, of kingship was often depicted as a separate entity standing behind the human ruler. This divine aspect of the office of kingship was what gave authority to the individual person who was the king. The living king was associated with the god Horus, the powerful, virile falcon-headed god who was believed to bestow the throne to the first human king.

Horus’s immensely important father, Osiris, was the lord of the underworld. One of the original divine rulers of Egypt, this deity embodied the promise of regeneration. Cruelly murdered by his brother Seth, the god of the chaotic desert, Osiris was revived through the potent magic of his wife Isis. Through her knowledge and skill, Osiris was able to sire the miraculous Horus, who avenged his father and threw his criminal uncle off the throne to take his rightful place.

Osiris became ruler of the realm of the dead, the eternal source of regeneration in the afterlife. Deceased kings were identified with this god, creating a cycle where the dead king fused with the divine ruler of the dead, and his successor “defeated” death to take his place on the throne as Horus.

The Development of Ancient Egypt

The civilization of Egypt obviously did not spring fully formed from the Nile mud; although the massive pyramids at Giza may appear to the uninitiated to have appeared out of nowhere, they were founded on thousands of years of cultural and technological development and experimentation.

Additional resources

More from Smarthistory on ancient Egypt’s early development and dynasties.

Read a Reframing Art History chapter on the world of ancient Egypt.

Read a Reframing Art History chapter about Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife.

Egyptian art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Source: Dr. Amy Calvert, “Ancient Egypt, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed July 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/ancient-egypt-an-introduction/.

Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife

by Dr. Amy Calvert

When most people think of ancient Egypt, the images that arise are usually pyramids, temples, tombs, and treasure. While daily life in Egypt left little trace archaeologically, tombs and temples are generally well preserved and provide a useful lens for understanding this complex civilization. As dazzling as many ancient Egyptian artifacts, images, and spaces are, and as aesthetically-pleasing as they may be, it is important to remember that most were not produced for a human audience. Instead, these are expressions of the primary driver in Egyptian culture—religion.

Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs created the foundation for their unique, largely theocratic, society. Despite being surrounded in layers of mystery, these beliefs shaped and directed the culture at almost every imaginable level. There were nearly 1,500 deities known by name, and they were believed to not only be responsible for creation but also involved in every aspect of the continued existence of the functioning cosmos. A closer examination of these deities reveals a sophisticated web of connections that only got richer as the centuries passed.

This chapter aims to provide a very basic introduction and general overview of the religious life of the ancient Egyptians. Inextricably linked with their daily lives as well as their afterlives, religious beliefs formed the primary framework around which everything else in this fascinating and long-lived culture grew.

Temples and Priests

Interactions with deities at their cult spaces (shrines) began very early in Egypt’s history. From the Predynastic period, the ancient Egyptians established shrines (made initially from reeds and mud) at sacred sites where the gods were believed to dwell. With the founding of the state, subsidized cults developed and the earliest kings of the unified Egypt traveled through the land, visiting cult sites and establishing their relationship with the gods. Over time, these simple structures eventually evolved into massive stone complexes.

These shrines were not merely places of worship—their primary function was to house the gods and serve as miniature models of the perfected cosmos. They provided an interface between the terrestrial and celestial realms. These structures, and the rituals that took place within them, functioned to preserve the proper cosmic order.

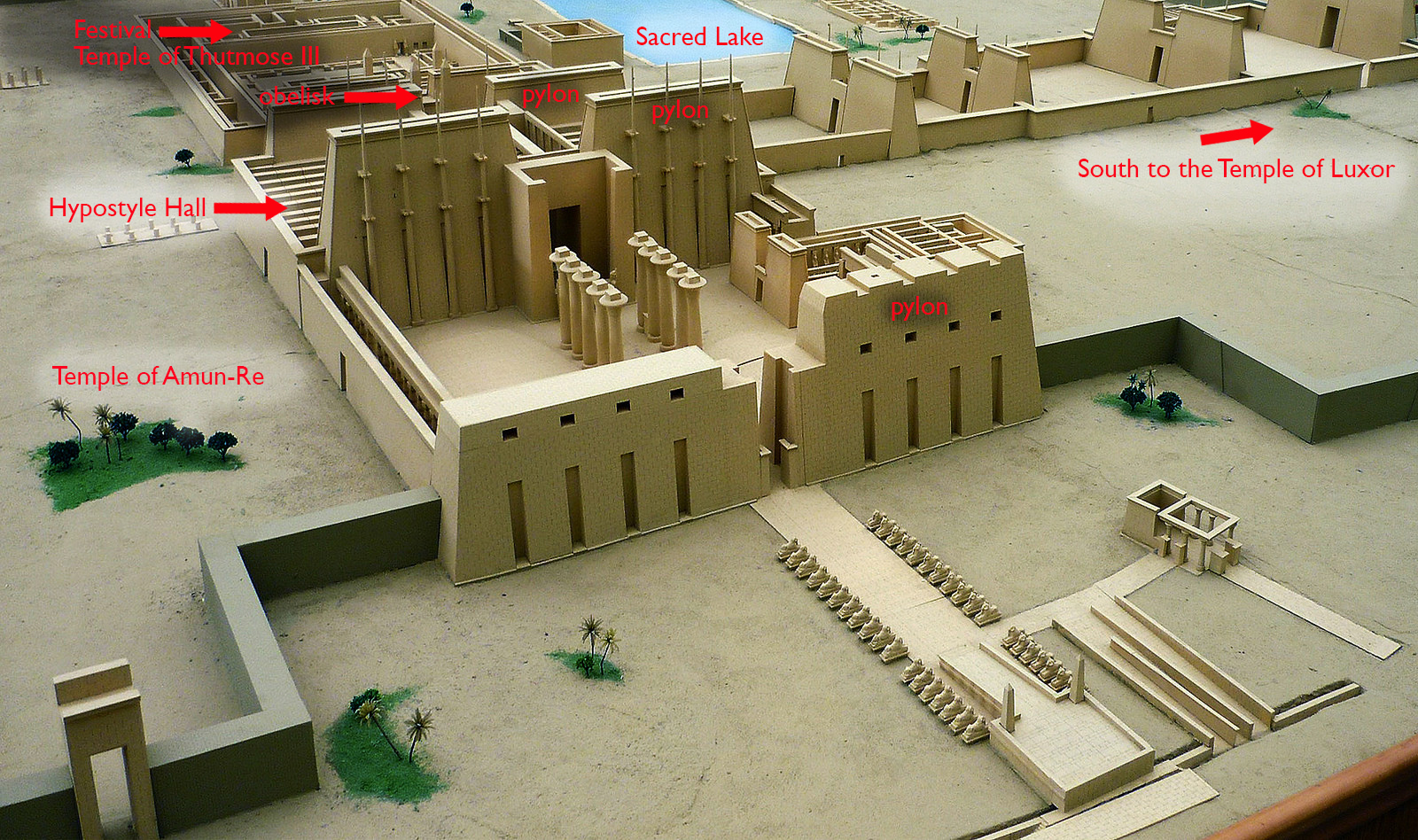

Temple architecture was explicitly designed to express this idea of the cosmos made manifest. This included temenos walls that separated the everyday world from the sacred space inside, pylon gateways shaped like the hieroglyph for “horizon,” an axial processional way that mirrored the path of the sun, and the dark, small, hidden space of the inner sanctuary that represented the mound of creation.

Carved on the walls were scenes depicting ritual actions being performed before the gods; in nearly all cases, the king was shown as chief officiant. These reliefs assisted in the perpetual enactment of the necessary rituals that kept the gods provisioned and ensured the perpetuation of the cosmos. By keeping the gods satisfied and serviced through the daily rituals that tended to their basic needs, they in turn were willing and able to sustain the functioning of the universe.

While in theory the king and the deities were the sole participants in the daily ritual cycle, in reality this function would have been served by priests. Priests acted as the king’s surrogates within the temples and performed the required daily cult activities. While in earlier periods temple service was performed as one of the rotational duties expected of local officials along with their more secular tasks, by the New Kingdom temple activities were undertaken by a professional, often hereditary, priesthood.

The focal point of the daily rituals was a cult image of the deity that was kept in the inner sanctuary of the temple. Often crafted from precious materials like gold, silver, and lapis lazuli, very few of these cult images have been preserved (they are small, so easily transportable). They were not viewed as gods themselves, but instead provided a ritually perfected place to house their spirits or manifestations. The daily rituals indicate that these cult images of the deity were treated almost as though they were alive. Rituals included washing the statues, anointing them, clothing them, adorning them with jewelry, censing them, and providing offerings of food and drink before returning them to their shrines again.

Personal Ritual and Daily Magic

Most people primarily interacted with the official cults during public festivals and processions that served to rejuvenate the gods. These festivals included removing the cult image from its shrine, often placing it on a special boat-shaped palanquin (known as a bark), and processing it along proscribed routes to visit other deities in their temples or to certain sacred locations. These public processions permitted the general population, which was denied access to the temple proper, to “interact” with their gods.

The general population could also gain access to the temple gods via special shrines placed outside the temple walls (often at the rear of the structure, lined up with the inner sanctuary) and at the feet of the colossal statues that stood at the front entrance and served as mediators.

While the vast majority of the population played no role in temple rituals, they could engage with formal religious spaces by presenting votive offerings as an expression of piety and dedication. Wealthy individuals donated statues of themselves presenting offerings to be placed in the temple. Other votive objects included stelae, statuettes, food offerings, mold-made faience amulets, and mummified sacred animals. Vast numbers of such votive objects were donated in temples over the millennia.

Many of these objects survive because after a period of time votive offerings would begin to fill the temple space, which then needed to be cleared out to make room for new offerings. Having been dedicated to the gods, these objects could not simply be discarded; instead, large collections were ritually buried on the temple grounds. Several examples of these ritual pits have been discovered and excavated. Referred to as caches, they preserved many exquisite statues as well as some of the most important ceremonial objects to have survived from antiquity—including the extraordinary Narmer Palette.

The wider concept of personal piety seems to have emerged during the First Intermediate Period (c. 2150–2030 B.C.E.). This practice permitted more direct divine access for common people via small local shrines, developing alongside the state temples, where prayers could be offered and votive objects dedicated. Many Egyptians also venerated personal deities in household shrines. Houses excavated in the New Kingdom village of Deir el-Medina provide numerous examples of such shrines, with niches where images of deceased relatives and household deities like Bes and Taweret were venerated. These deities were believed to have the ability to ward off evil and also appear in the form of wearable amulets intended to serve the same function.

Mortuary Practices

Body and Identity

Funerary beliefs developed that required the body of the deceased to be preserved and kept identifiable so the spirit could return to it. In the earliest burials, bodies were dried out by desiccation in the arid desert conditions; some of these natural mummies are quite well preserved. The processes used to preserve the body became quite complex. Performed by a special class of priests, there were different levels of mummification depending on economic status, with a wide range in cost and overall success.

Tombs

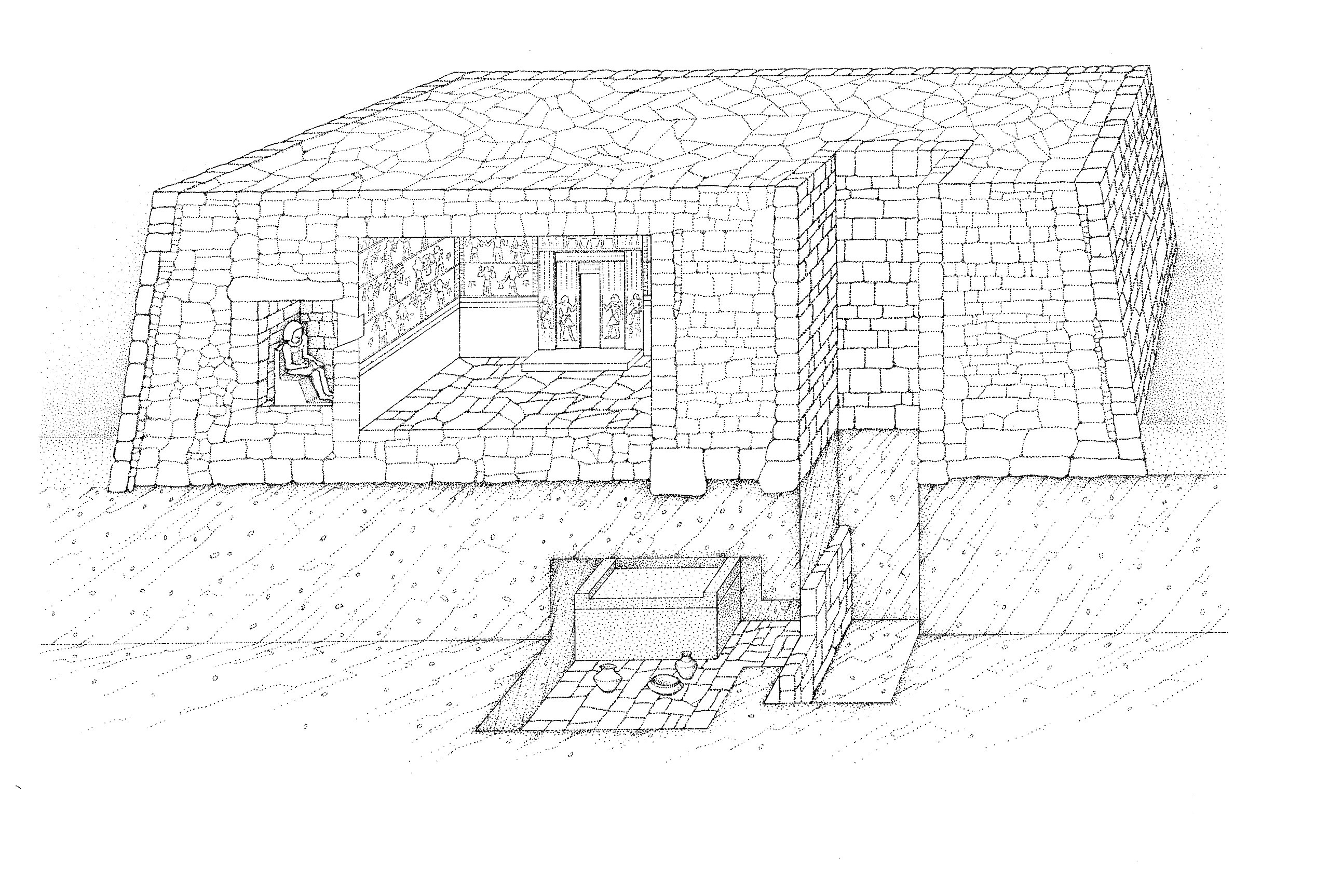

Most Egyptian tombs had two primary components: 1) a sealed-off subterranean chamber containing the body and grave goods, and 2) a superstructure with a chapel that could be visited by family and friends to perform rituals and leave offerings.

Royal mortuary monuments of the Early Dynastic period (c. 3000–2686 B.C.E.) at the site of Abydos consisted of a large mud brick ritual enclosure near the cultivated land and a subterranean tomb dug several kilometers to the west near an opening in the desert cliffs believed to be the entrance to the netherworld. With Djoser at the beginning of the Third Dynasty, these mortuary features were combined into a single, massive complex at Saqqara.

Pyramid complexes of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2150 B.C.E.), including the well-known Great Pyramid at Giza, consisted of several elements besides the pyramid itself, including multiple temples, stone-lined causeways, smaller subsidiary pyramids and chapels, and buried boats.

Elites were buried in large cemeteries that surrounded the tombs of their kings, in flat-topped brick structures known as mastabas. Nearly solid, these private tombs consisted of the sealed burial, below ground, and a chapel cut into the side of the mastaba for the veneration of the deceased.

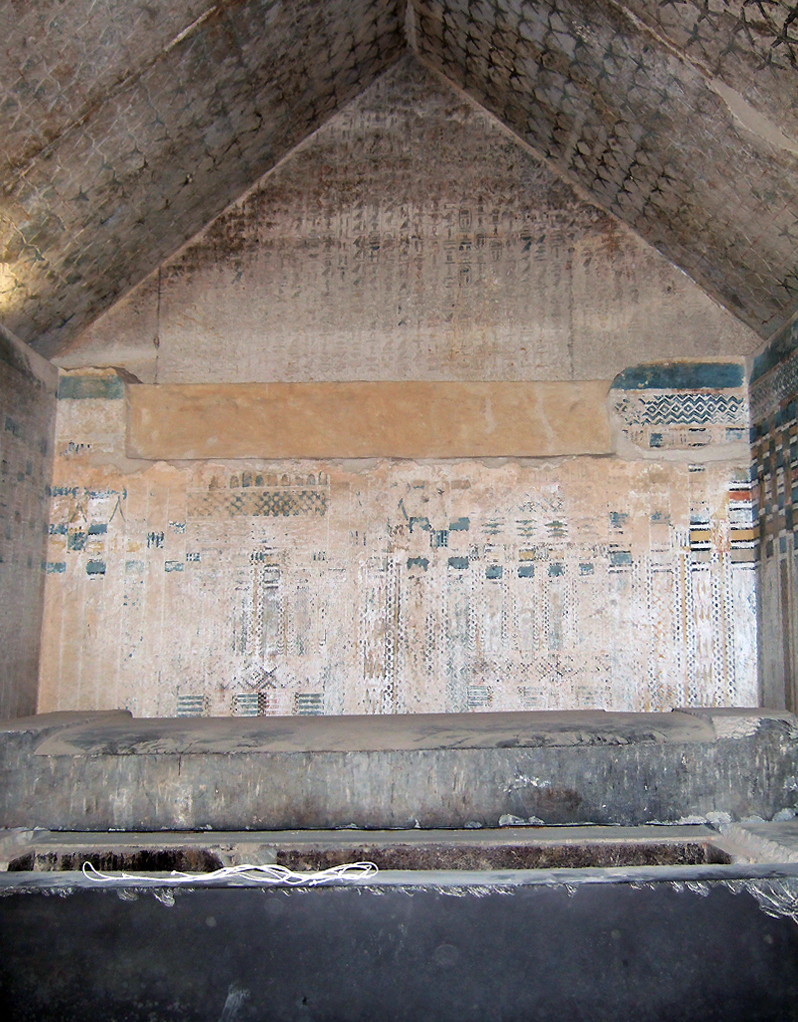

Royal burial chambers came to be covered with lines of text by the Fifth Dynasty, such as those in the pyramid of King Unas. Pyramid Texts, as they are now known, were among the earliest religious writings on the planet. This collection of recitations and instructions was designed to help the deceased in their afterlife journey.

Royal pyramid tombs of the Middle Kingdom did not contain inscriptions. These complexes, with their elaborate mortuary temples, are unfortunately not well preserved. This was largely due to the construction methods used during this period, where the pyramids had a core of mud brick encased in stone blocks. Later looting of the casing stones resulted in extreme weathering of the exposed mud brick. Many private burials were better preserved and included painted coffins covered with texts and scenes intended to aid the deceased in the afterlife. This collection of funerary literature is now referred to as the Coffin Texts.

During the New Kingdom, royal tombs were carved deep into the hills of western Thebes, in a place now known as the Valley of the Kings. These hidden burials were conceptually paired with large memorial temples constructed closer to the land of the living on the edge of the cultivated land. These structures were used for the king’s mortuary cult, providing the deceased ruler with all the offerings and necessary rituals to ensure their idealized continuation in the netherworld.

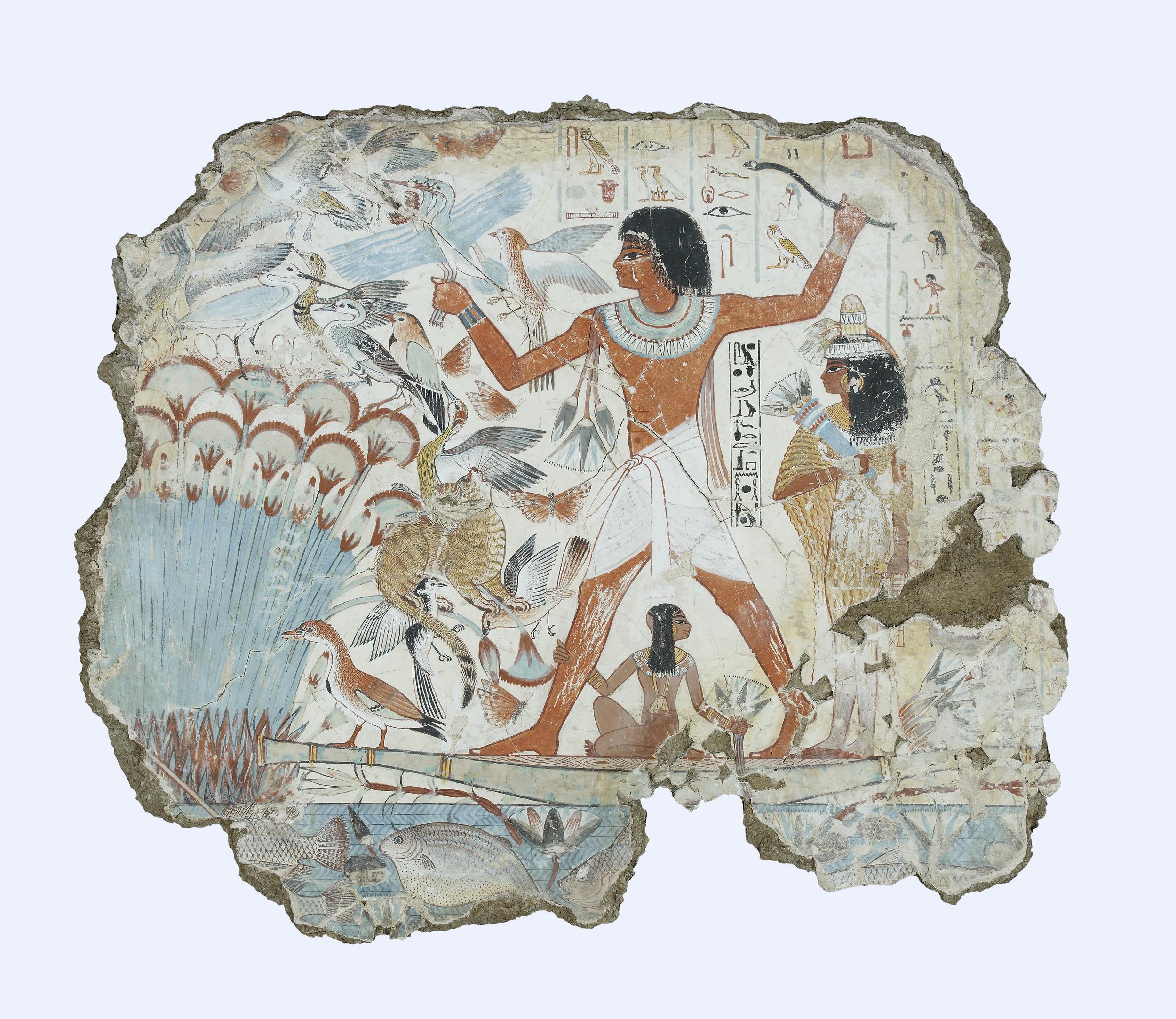

Private tombs in the New Kingdom continued to include elaborately decorated chapels with scenes and texts related to important events from the life of the deceased and ritual scenes designed to provide for them in the afterlife. Some preserved scenes depict lively and vibrant representations of their life on Earth.

Journey of the Deceased

After the funeral rites and burial, the deceased began their netherworld journey toward the land of Osiris, aided by mortuary texts like the Book of the Dead that would be included in their tomb. These texts provided a sort of road map and specified the spells needed to successfully traverse this dangerous realm and get past the guardians and gatekeepers they encountered along the way.

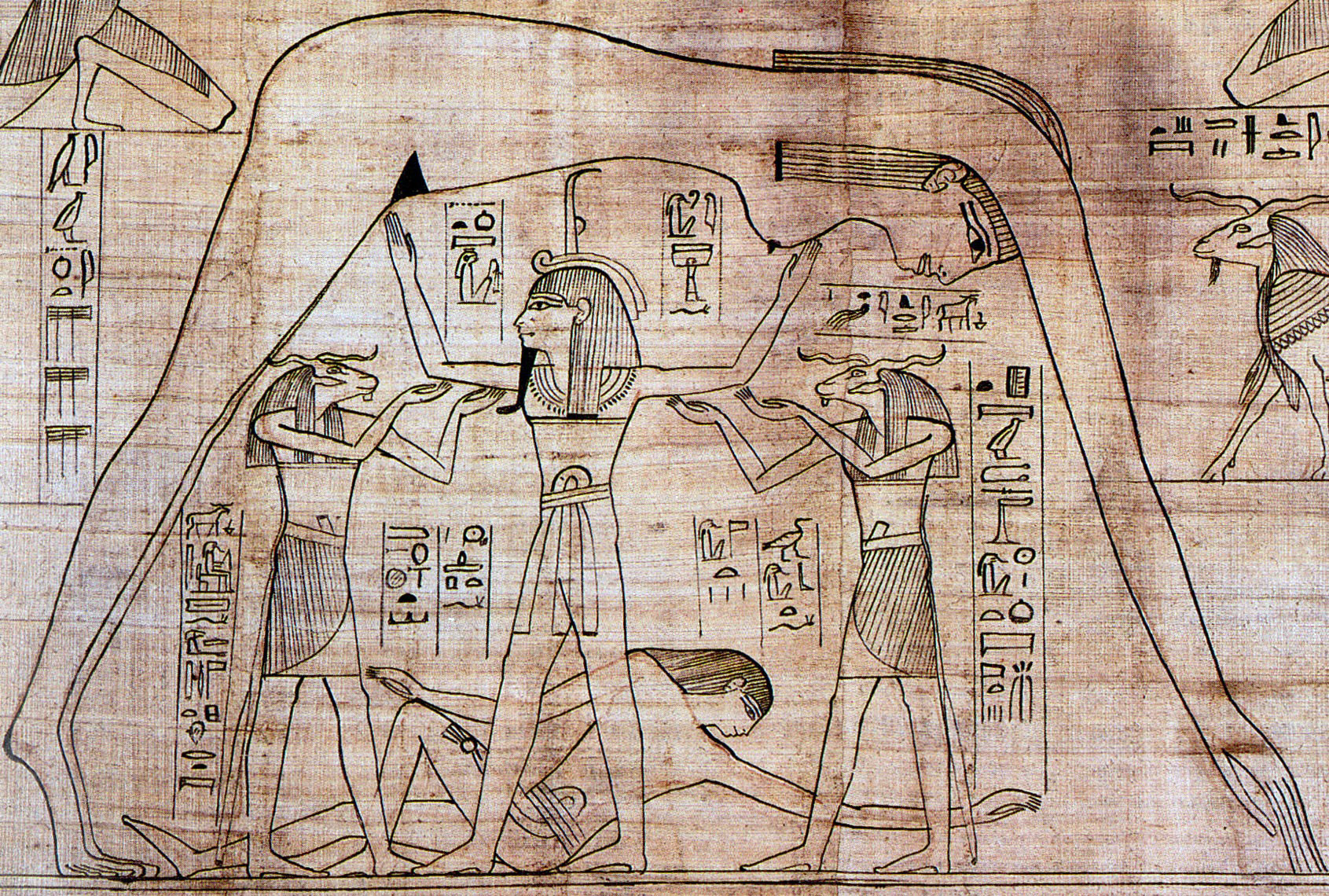

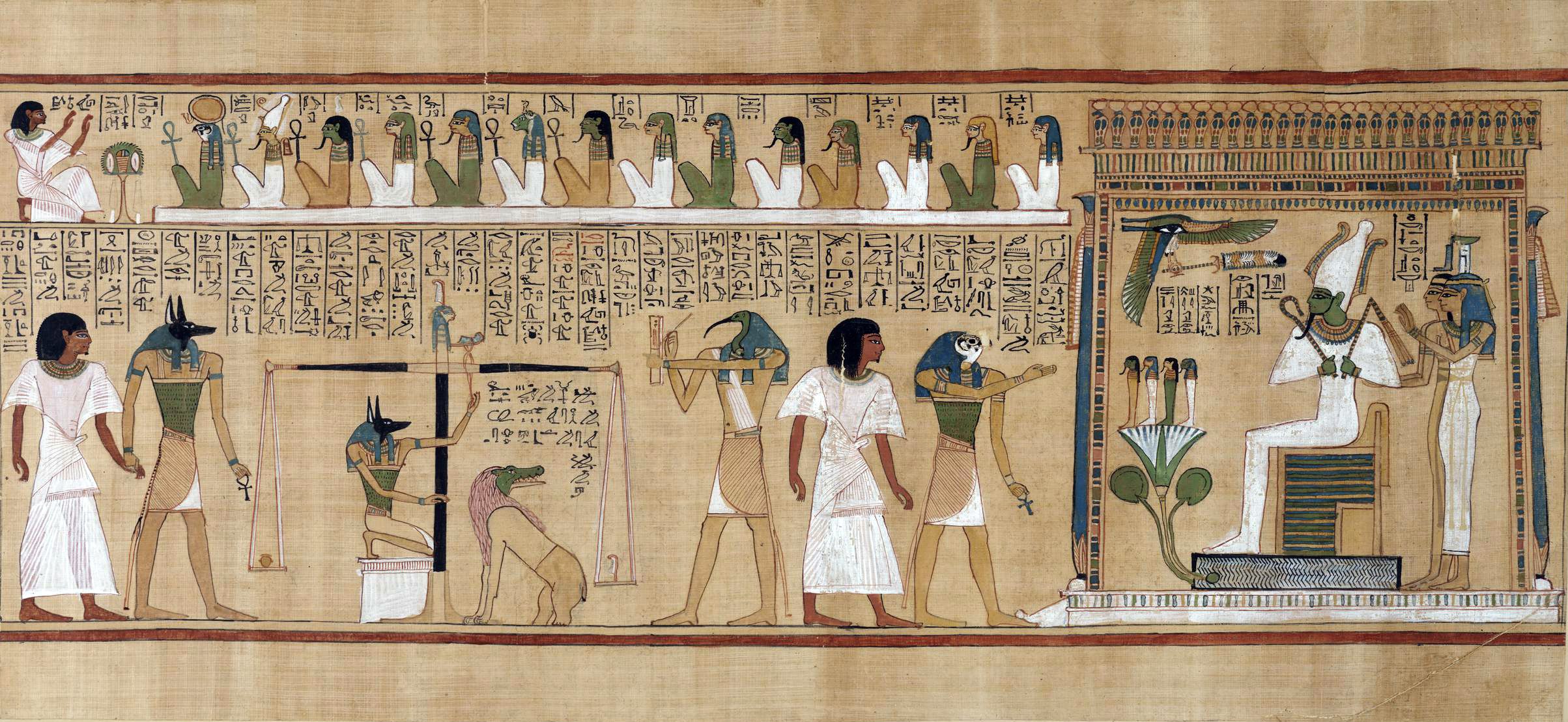

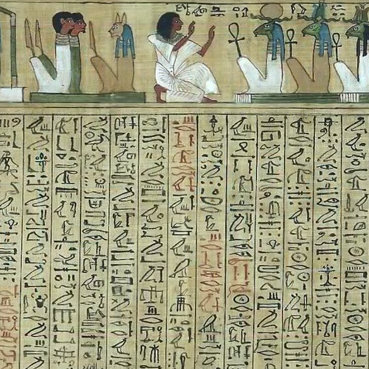

Eventually, the deceased reached the last judgment. This vitally important moment decided their fate. As they stood before the enthroned Lord of the Dead, Osiris, their heart was weighed on a scale against the feather of ma’at. Usually, a small image of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and cosmic balance, stood atop the scales to confirm the correctness of the weighing. The jackal-headed funerary god Anubis oversaw the weighing of the heart while the ibis-headed Thoth recorded the verdict. If their heart was “light as a feather,” the blessed dead were permitted to enter the idealized afterlife known as the Field of Reeds. For the unfortunate Egyptian whose heart was heavier than the feather of truth, a horrific monster with the head of a crocodile, body of a lion, and hindquarters of a hippopotamus—known as Ammit—waited eagerly to devour their heart and damn them to eternal oblivion. Obviously, in scenes of this judgment, the Egyptians always portrayed the scales balancing or with the heart even slightly lighter than the feather.

Religion was woven into every aspect of life for the ancient Egyptian, whether king or commoner. The complex web created by the layers of rituals and stories that developed over the millenia provided the flexible structure that functioned as the psychological core for this enigmatic culture. Striving for the cosmic balance of ma’at in their daily lives, Egyptian society achieved largely-stable longevity and enjoyed great peaks that would suggest that they were doing at least something right.

Source: Dr. Amy Calvert, “Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife,” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, August 2, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/ancient-egyptian-religious-life-and-afterlife/.

Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Overview

It is not known exactly where and when Egyptian writing first began, but it was already well-advanced two centuries before the start of the First Dynasty that suggests a date for its invention in Egypt around 3,000 B.C.E. The most well-known script used for writing the Egyptian language was in the form of a series of small signs, or hieroglyphs.

Some signs are pictures of real-world objects, while others are representations of spoken sounds. These sound signs are pictures that get their meaning from how the word for the object they represent sounds when said aloud. Some signs write one letter, some more, while others write whole words.

Like cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs were used for record-keeping, but also for monumental display dedicated to royalty and deities. The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek hieros ‘sacred’ and gluptien ‘carved in stone’. The last known hieroglyph inscription was 394 C.E.

Other scripts used to write Egyptian were developed over time. Hieratic was handwritten and easier to write so was used for administrative and non-monumental texts from the Old Kingdom (about 2613–2160 B.C.E.) to around 700 B.C.E. Hieratic was replaced by demotic, which means popular, in the Late Period (661–332 B.C.E.), and was a more abbreviated version. In turn demotic was replaced by Coptic, which may have been introduced to record the contemporary spoken language, in the first century C.E.

Labels

Most ivory plaques dating to the First Dynasty were made as labels. The pair of sandals incised on the back of this one indicates that it was a label for sandals, which were extremely prestigious items.

Labels such as these were usually decorated with representations of important events and this example shows Den, the fifth king of the First Dynasty, about to bring his mace down on the head of his vanquished enemy. The name of the king is written in the rectangular frame in front of his face, with the figure of a falcon, a symbol of royalty, above. The hieroglyphs behind the king give the name of one of his high officials, Inka.

This label is one of the few sources for information about activity inside or outside Egypt in the Early Dynastic period. The hieroglyphs on the right-hand side of the label read ‘first occasion of smiting the East’. That the enemy is an Easterner is indicated by his long locks and pointed beard. The gravel-spotted desert which serves as a ground-line rises to a hill on the right, suggestive of Egyptian depictions of foreign lands.

Such illustrations are a standard way of depicting kings and do not necessarily mean that any such campaign ever took place. Kings are shown, over a period of 2,000 years, smiting Libyan chiefs—some with the same name! However, all standard motifs must have a prototype, and, being one of the earliest known, this example might refer to a real historical event.

Written in Black and Red

The hieroglyphic sign for ‘write’ was formed from an image of the scribal palette and brush case. Statues of scribes are sometimes shown with a papyrus across their knees and a palette, the scribe’s trademark, over one shoulder.

From the late Old Kingdom on, the basic palette was made of a rectangular piece of wood, with two cavities at one end to hold cakes of black and red ink. Carbon was used to make the black ink and iron-rich red ochre to make the red. Both pigments were mixed with gum so that they congealed rather than turned to dust when they dried. The cakes of ink were moistened with a wet brush, rather like modern watercolors or Chinese ink. Brush-pens were made of rushes, the tip cut at an angle and chewed to separate the fibers. These were kept in a slot in the middle of the palette.

Black was the normal color for writing. Red was used to mark the start of a text, or to highlight key words and phrases, like quantities in medicines, or for the names of demons in religious papyri. More colors were needed for illustrations, such as those in the Book of the Dead.

Source: The British Museum, “Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs overview,” in Smarthistory, August 15, 2016, accessed August 12, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/ancient-egyptian-hieroglyphs/.