6.5 Eastern Asia

The Silk Road

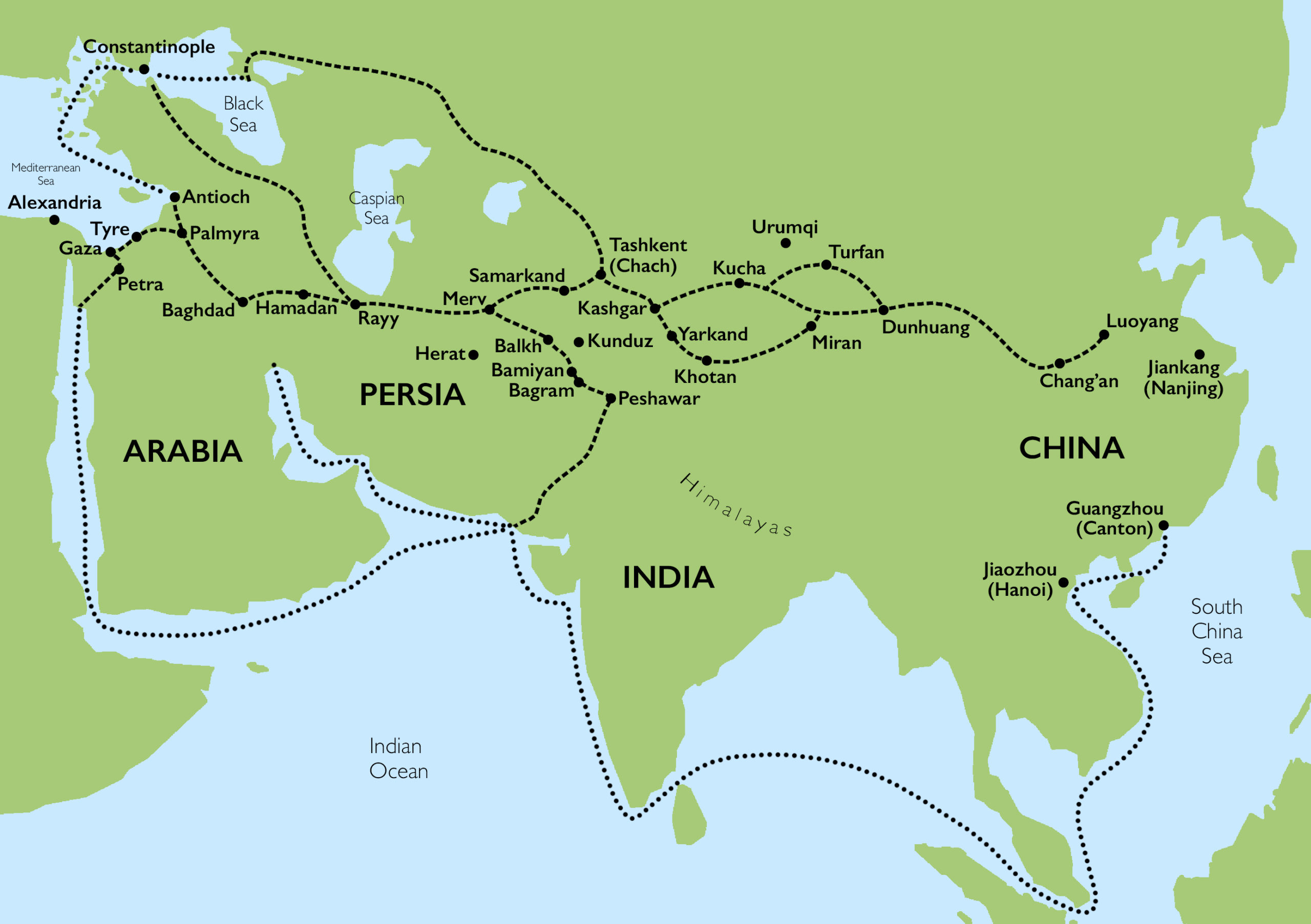

The name “Silk Road” is familiar to many, conjuring up caravan trains of camels crossing deserts weighed down by exotic goods such as tea, spices, medicines, and crucially, silk, but the reality of the Silk Roads was both more complex and more ordinary. The Silk Roads were a network of trade routes that connected towns and peoples across Asia that flourished from about 200–900 C.E. but existed from about 100 B.C.E. through the mid-1400s C.E. The foundation of the “Silk Roads” is attributed to Han dynasty envoy, Zhang Qian, whose mission to Central Asia in 114 B.C.E. brought the Chinese court into direct contact with kingdoms in Central Asia.

The phrase “Silk Road,” invokes a pre-modern cross-continental highway, but the idea of a road meandering across Asia is relatively recent. The name “Silk Road” was given to the network of ancient trade routes crossing Asia by the German traveler and geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. Goods (including art objects, textiles, medicine, and foods) and ideas (including religious thought and philosophical concepts) certainly traveled very impressive distances along these trade routes, but most of the travel was relatively local in scope.

Many of the same routes continued to be used by later traders and travelers, but the combination of short and long-distance trade that characterized these overland routes shifted beginning in the 10th century. This occurred for several reasons, including the fall of the Tang dynasty in China; the rise of maritime trade routes through Southeast Asia that allowed for goods and people to travel long distances much more quickly; and the absorption of communities of Sogdians, merchants who were responsible for much of the long-distance Silk Road trade, by Islamic empires. Pan-Asian exchange flourished again in the Mongol period in the 13th and 14th centuries which saw Mongol rule over most of Asia, sometimes following the old Silk Roads overland, sometimes following the maritime trade routes that had been established between the decline of the overland Silk Roads and rise of the Mongols.

Asia is the primary focus of Silk Road trade, but it can be argued that the Silk Roads extended as far west as Rome, as attested by the presence of Roman glass bowls and other objects found in tombs in China and the Korean peninsula. Chinese silk was also highly sought after by Roman elites beginning as early as the second century B.C.E. Beginning in the fourth century C.E., the interconnectivity between Central Asia and the Eastern Roman Empire, which brought Asian goods into the Mediterranean, can also be understood as part of the Silk Roads.