3.1 Geography and History

Etruria

Before the small village of Rome became “Rome” with a capital R (to paraphrase the author D. H. Lawrence), a brilliant civilization once controlled almost the entire peninsula we now call Italy. This was the Etruscan civilization, a vanished culture whose achievements set the stage not only for the development of ancient Roman art and culture but for the Italian Renaissance as well.

Though you may not have heard of them, the Etruscans were the first “superpower” of the Western Mediterranean who, alongside the Greeks, developed the earliest true cities in Europe. They were so successful, in fact, that the most important cities in modern Tuscany (Florence, Pisa, and Siena, to name a few) were first established by the Etruscans and have been continuously inhabited since then.

Yet the labels “mysterious” or “enigmatic” are often attached to the Etruscans since none of their own histories or literature survives. This is particularly ironic as it was the Etruscans who were responsible for teaching the Romans the alphabet and for spreading literacy throughout the Italian peninsula.

The Influence on Ancient Rome

Etruscan influence on ancient Roman culture was profound. It was from the Etruscans that the Romans inherited many of their own cultural and artistic traditions, from the spectacle of gladiatorial combat, to hydraulic engineering, temple design, and religious ritual, among many other things. In fact, hundreds of years after the Etruscans had been conquered by the Romans and absorbed into their empire, the Romans still maintained an Etruscan priesthood in Rome (which they thought necessary to consult when under attack from invading “barbarians”).

We even derive our very common word “person’” from the Etruscan mythological figure Phersu—the frightful, masked figure you see in this Early Etruscan tomb painting who would engage his victims in a dreadful “game” of blood letting in order to appease the soul of the deceased (the original gladiatorial games, according to the Romans!).

Etruscan Art and the Afterlife

Early on the Etruscans developed a vibrant artistic and architectural culture, one that was often in dialogue with other Mediterranean civilizations. Trading of the many natural mineral resources found in Tuscany, the center of ancient Etruria, caused them to bump up against Greeks, Phoenicians, and Egyptians in the Mediterranean. With these other Mediterranean cultures, they exchanged goods, ideas, and, often, a shared artistic vocabulary.

From their extensive cemeteries, we can look at the “world of the dead” and begin to understand some about the “world of the living.” During the early phases of the Etruscan civilization, they conceived of the afterlife in terms of life as they knew it. When someone died, he or she would be cremated and provided with another “home” for the afterlife.

This type of hut urn, made of an unrefined clay known as impasto, would be used to house the cremated remains of the deceased. Not coincidentally, it shows us in miniature form what a typical Etruscan house would have looked like in Iron Age Etruria—oval with a timber roof and a smoke hole for an internal hearth.

More Opulent Tombs

Later on, houses for the dead became much more elaborate. During the Orientalizing period, when the Etruscans began to trade their natural resources with other Mediterranean cultures and became staggeringly wealthy as a result, their tombs became more and more opulent.

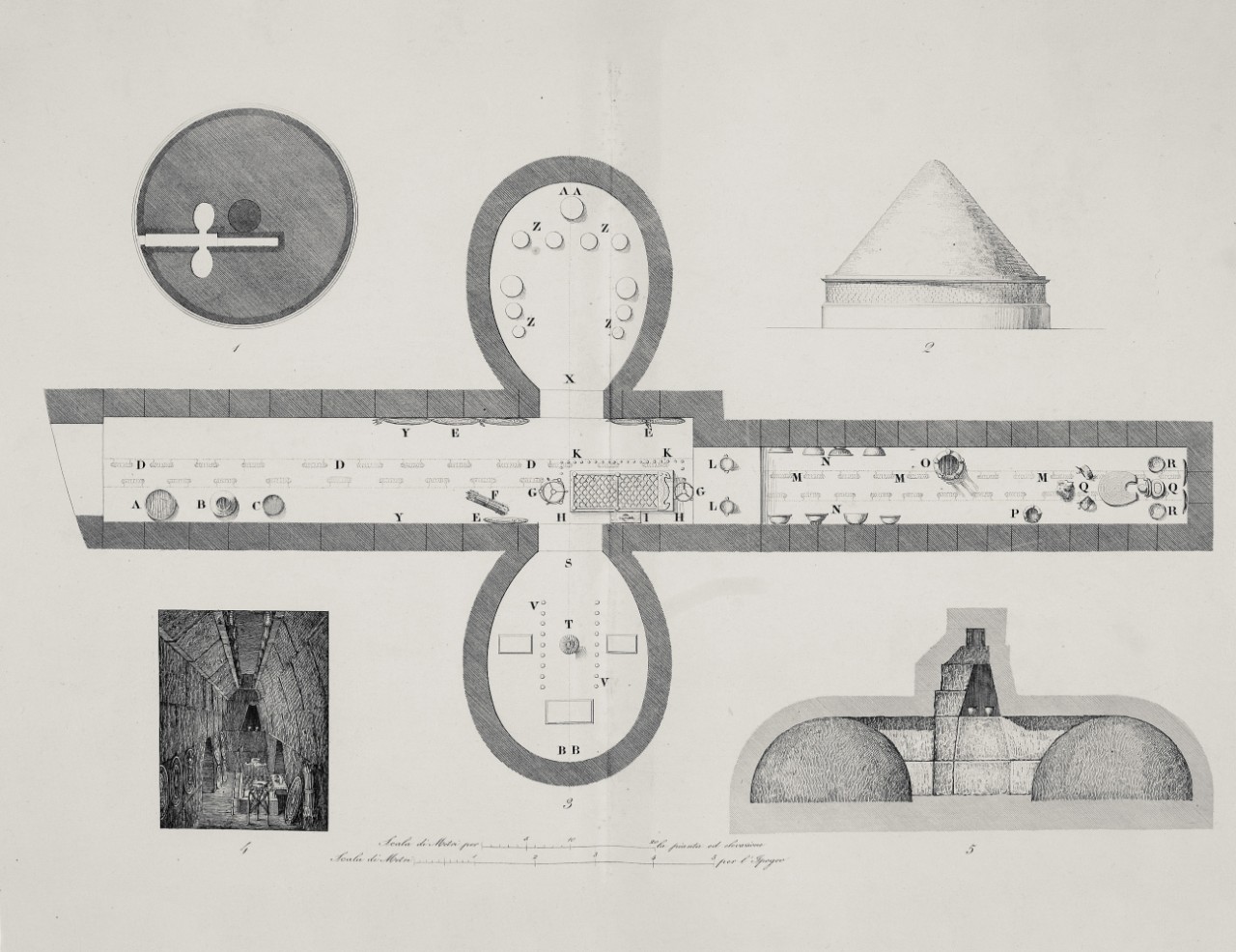

The well-known Regolini-Galassi tomb from the city of Cerveteri shows how this new wealth transformed the modest hut to an extravagant house for the dead. Built for a woman clearly of high rank, the massive stone tomb contains a long corridor with lateral, oval rooms leading to a main chamber.

A stroll through the Etruscan rooms in the Vatican Museum where the tomb artifacts are now housed presents a mind-boggling view of the enormous wealth of the period. Found near the woman were objects of various precious materials intended for personal adornment in the afterlife—a gold pectoral, gold bracelets, a gold brooch (or fibula) of outsized proportions, among other objects—as well as silver and bronze vessels, and numerous other grave goods and furniture.

Of course, this important woman might also need her four-wheeled bronze-sheathed carriage in the afterlife as well as an incense burner, jewelry of amber and ivory, and, touchingly, her bronze bed around which thirty-three figurines, all in various gestures of mourning, were arranged.

Though later periods in Etruscan history are not characterized by such wealth, the Etruscans were, nevertheless, extremely powerful and influential and left a lasting imprint on the city of Rome and other parts of Italy.

Copyright: Dr. Laurel Taylor, “The Etruscans, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed April 2, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-etruscans-an-introduction/.

Rome

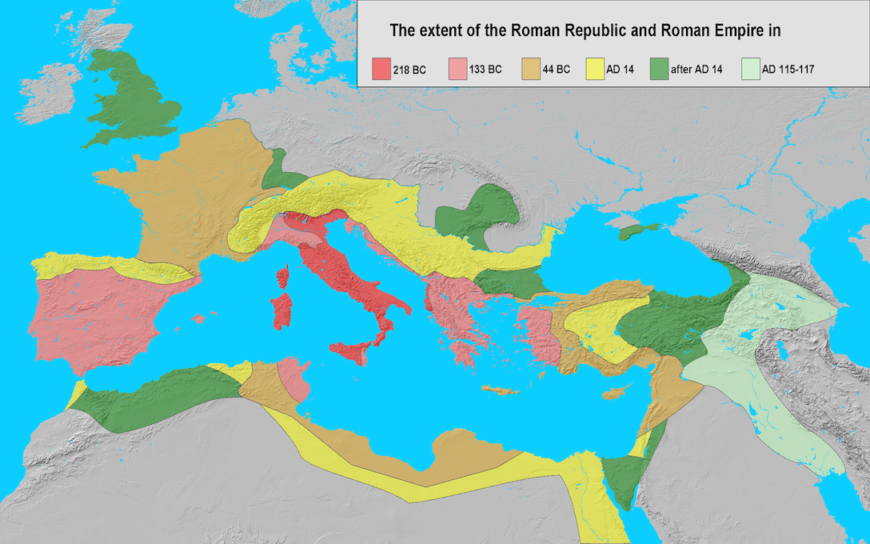

Legend has it that Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E. by Romulus, its first king. In 509 B.C.E. Rome became a republic ruled by the Senate (wealthy landowners and elders) and the Roman people. During the 450 years of the Republic, Rome conquered the rest of Italy and then expanded into France, Spain, Turkey, North Africa, and Greece.

The Capitoline She-wolf (Italian: Lupa capitolina) takes its name from its location—the statue is housed in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The She-wolf statue is a fully worked bronze composition that is intended for 360 degree viewing. In other words the viewer can get an equally good view from all directions: there is no “correct” point of view. The She-wolf is depicted standing in a stationary pose. The body is out of proportion, because its neck is much too long for its face and flanks. The incised details of the neck show thick, s-curled fur which ends with unnatural beads around the face and behind the forelegs. The wolf’s body is leaner in front than in the rear: its ribs are visible, as are the muscles of its forelegs, while in the back the musculature is less detailed, suggesting less tone. Its head curves in towards its tail; the ears curve back. The children themselves have a more dynamic posture: one sits with his feet splaying to either side, while the other kneels beside him. Both face upwards. They, too, are lean, with no trace of baby fat. The children represent Romulus and Remus, the twin children, raised by the She-wolf, per the Etruscan myth, who grew up to build a city of the Palatine Hill. The brothers feuded over who would rule the city and, in an altercation, Romulus killed his brother Remus to become and sole ruler and founder of Rome.

Rome became very Greek-influenced or “Hellenized,” and the city was filled with Greek architecture, literature, statues, wall-paintings, mosaics, pottery, and glass. But with Greek culture came Greek gold, and generals and senators fought over this new wealth. The Republic collapsed in civil war and the Roman empire began.

In 31 B.C.E. Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, defeated Cleopatra and Mark Antony at Actium. This brought the last civil war of the Republic to an end. Although it was hoped by many that the Republic could be restored, it soon became clear that a new political system was forming: the emperor became the focus of the empire and its people. Although, in theory, Augustus (as Octavian became known) was only the first citizen and ruled by consent of the Senate, he was in fact the empire’s supreme authority. As emperor he could pass his powers to the heir he decreed and was a king in all but name.

The empire, as it could now be called, enjoyed unparalleled prosperity as the network of cities boomed, and goods, people, and ideas moved freely by land and sea. Many of the masterpieces associated with Roman art, such as the mosaics and wall paintings of Pompeii, gold and silver tableware, and glass, including the Portland Vase, were created in this period. The empire ushered in an economic and social revolution that changed the face of the Roman world: service to the empire and the emperor, not just birth and social status, became the key to advancement.

Successive emperors, such as Tiberius and Claudius, expanded Rome’s territory. By the time of the emperor Trajan, in the late first century C.E., the Roman empire, with about fifty million inhabitants, encompassed the whole of the Mediterranean, Britain, much of northern and central Europe, and the Near East.

Starting with Augustus in 27 B.C.E., the emperors ruled for five hundred years. They expanded Rome’s territory and by about 200 C.E., their vast empire stretched from Syria to Spain and from Britain to Egypt. Networks of roads connected rich and vibrant cities, filled with beautiful public buildings. A shared Greco-Roman culture linked people, goods and ideas.

The imperial system of the Roman Empire depended heavily on the personality and standing of the emperor himself. The reigns of weak or unpopular emperors often ended in bloodshed at Rome and chaos throughout the empire as a whole. In the third century C.E. the very existence of the empire was threatened by a combination of economic crisis, weak and short-lived emperors and usurpers (and the violent civil wars between their rival supporting armies), and massive barbarian penetration into Roman territory.

Relative stability was re-established in the fourth century C.E., through the emperor Diocletian’s division of the empire. The empire was divided into eastern and western halves and then into more easily administered units. Although some later emperors such as Constantine ruled the whole empire, the division between east and west became more marked as time passed. Financial pressures, urban decline, underpaid troops, and consequently overstretched frontiers—all of these finally caused the collapse of the western empire under waves of barbarian incursions in the early fifth century C.E. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed in 476 C.E., though the empire in the east, centered on Byzantium (Constantinople), continued until the fifteenth century.

Copyright: The British Museum, “Introduction to ancient Rome,” in Smarthistory, March 1, 2017, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-ancient-rome/.