9.4 Music

American Vernacular Music

Western culture has tended to divide musical practices into two very broad fields, the vernacular and the cultivated. Vernacular refers to everyday, informal musical practices located outside the official arena of high culture—the conservatory, the concert hall, and the high church. The field of vernacular music is often further subdivided into the domains of folk music (orally transmitted and community based) and popular music (mediated for a mass audience). Cultivated music, often referred to as classical or art music, is associated with formal training and written composition. The boundaries between so-called folk, popular, and classical music are becoming increasingly blurred as we enter into the 21st century, due to the pervasive effects of mass media that have made music of all American ethnic/racial groups, classes, and regions available to everyone.

Historians and musicologists now agree that America’s most distinctive musical expressions are found, or have roots in, its vernacular music. Early immigrants from Western Europe and the slaves stolen from Africa brought with them rich traditions of oral folk music that mixed and mingled throughout the 18th and 19th centuries to develop uniquely American ballads, instrumental dance music, and spirituals. By the early 20th century, the folk blues emerged and would go on to form the foundation of much of our popular music. Beginning with 19th century minstrel and parlor song collections, and threading through the 20th century recordings of Tin Pan Alley song, gospel, rhythm and blues, country, rock, soul, and rap, the print and electronic media fueled the growth of American popular musical styles that today have proliferated across the globe. Jazz, sometimes considered America’s “classical” music, certainly had roots in early 20th century folk and popular styles (see Chapter 7: Jazz). And many of America’s best-known classical composers including George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Duke Ellington based their extended compositions on vernacular folk and popular themes (see Chapter 5: European and American Art Music since 1900).

American Folk Music

Folk music was once thought of as being simple, old, anonymously composed music played by poor, rural, nonliterate people representing the lower strata of our society (mountain hillbillies, southern black sharecroppers, cowboys, etc.). Today scholars have expanded the field by defining folk music as orally transmitted songs and instrumental expressions that are passed on in community settings and generally show a degree of stability over time. Rather than viewing folk expressions as vanishing antiquities, this perspective suggests folk music can be a dynamic process that continues to flourish within many communities of our modern society. Using this model popular music may be defined as mass-mediated expression that changes rapidly over time, and classical/art music as musical practices centered in formal training and written composition.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American folk music collectors wrote down the words and melodies to a variety of traditional expressions including Native American ritual songs, African American spirituals and work songs, Anglo American ballads and fiddle tunes, and western cowboy songs. Later they broadened their interest to include the traditional expressions of ethnic and immigrant communities such as the practices of Hispanic, Irish, Jewish, Caribbean, and Chinese Americans, most of whom lived in urban areas. With the advent of portable recording technology in the 1930s, folklorists like Alan Lomax began the task of documenting America’s folk music and compiling the Archive of American Folk Song, which today, along with the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, offers students the chance to hear and study authentic regional folk styles.

Most Anglo and African American folk genres are built around relatively simple (often pentatonic) melodies, duple or triple meter time signatures, and a series of harmonic structures built around the tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords. But much of the emotional appeal of folk music comes from the grain or tension of the voice. Vocal textures vary greatly, ranging from the high, tense, nasal delivery associated with white mountain singers, to the more relaxed, throaty, rough timbre of southern African American blues and spiritual singers.

In addition to studying song texts and melodies, folk music scholars have paid a great deal of attention to the social function of folk music. They seek to understand how a particular song or instrumental piece works within a specific social situation for a particular group of people. For example, how do Native American chants and African American spirituals operate within the context of a religious or worship ceremony; how are Anglo and Celtic American fiddle tunes central to Appalachian and community gatherings; how did traditional blues and ballads reflect contrasting world views of southern blacks and whites; and how do West Indian steel bands and Jewish klezmer ensembles serve as markers of cultural pride?

The self-conscious revival of folk music by middle-class urban Americans has been going on since the 1930s. During the Depression and WWII years, folk artists like Louisiana-born Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter and Oklahoma-born Woody Guthrie introduced city audiences to rural folk music, and along with left-leaning topical folk singers like Pete Seeger, they helped spawn the great folk revival of the post–World War II years. Folk music spilled into the popular arena with artists like the Kingston Trio; Burl Ives; Peter, Paul & Mary; and Bob Dylan writing and recording hit folk songs.

Anglo American Ballads

Ballads are basically folk songs that tell stories through the introduction of characters in a specific situation, the building up of dramatic tension, and the resolution of that tension. Ballads were originally brought to America by British, Scottish, and Scotch-Irish immigrants, many of whom eventually settled in the mountainous regions of the American south.

The melodies of Anglo American ballads are simple, often built around archaic sounding pentatonic (five note) and hexatonic (six-tone) scales that may feature large jumps or gaps between notes. Songs are traditionally sung a cappella in a free meter style, or with simple guitar or banjo accompaniment. The voice is delivered in a high, tense, nasal style.

Ballads are most often set in four line stanzas, with the second and fourth line rhyming:

I was born in West Virginia,

among the beautiful hills.

And the memory of my childhood,

lies deep within me still.

While older British and Scottish ballads found in the American South dealt with themes of ancient kings, queens, and magical happenings in faraway places, the 18th- and 19th -century ballads that developed in America tell stories of everyday folk involved in everyday life events, usually set in the present or recent past. Sentimental and tragic love stories, often involving violence and death, were common. Many American ballads express strong moral sentiments, warning listeners about the consequences of irresponsible behavior:

I courted a fair maiden,

her name I will not tell

For I have now disgraced her,

and I am doomed to hell.

It was on one beautiful evening,

the stars were shining bright

And with that faithful dagger,

I did her spirit flight.

So justice overtook me,

you all can plainly see.

My soul is doomed forever,

throughout eternity.

The sentimental and tragic themes of Anglo American ballads, along with the high-pitched, “whiny” vocal style, have survived and flourished in 20th-century popular country music.

African American Spirituals and Gospel Music

The African American Spiritual has its origins in the religious practices of 18th- and 19th -century American slaves who converted to Christianity during the great awakening revivals. The earliest spirituals were African-style ring shouts, based on simple call and response lyrics chanted against a driving rhythm produced by clapping and foot stomping. Participants would shuffle around in a ring-formation and “shout” when they felt the spirit. More complex melodies and verse/chorus structures began to evolve, reflecting the influence of European American hymn singing, and accompaniment by guitar, piano, and percussion became common. Vocal ornamentations (slides, glides, extended use of falsetto), call and response singing, and blues tonality characterized these folk spirituals. In the reconstruction period black college choirs such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers arranged folk spirituals into four-part harmony, a form that became known as the concert spiritual. A blend of African and European musical practices, the spiritual epitomizes the sycretic (blended) nature of much American folk music resulting from the mixing of Africans and Europeans in the Americas.

The texts of many spirituals are taken from Old Testament themes and stories. The slaves were particularly moved by Old Testament figures like Daniel (who was saved from the lion’s den), Jonah (who was delivered from the belly of the whale), Noah (who survived the flood), and David (who defeated the giant Goliath) who struggled and triumphed over adverse conditions. The plight of the Israelites and their escape from bondage to the promised land was an especially powerful story retold by the spirituals:

When Israel was in Egypt’s land,

O let my people go!

Oppressed so hard they could not stand,

O let my people go!

Go Down, Moses,

Away down to Egypt’s land.

And tell old Pharaoh,

To let my people go!

The spiritual’s emphasis on redemption and deliverance in this world have led historians to suggest the songs had double meaning for the slaves—they affirmed their belief in the Bible as well as their trust that a just God would deliver them from the evils of slavery. The spirituals are thus seen as expressions of religious faith and resistance to slavery.

In the 20th-century spirituals evolved into the more urban, New Testament–centered gospel songs. Following the first “great migration” of southern African Americans to urban centers like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia in the post–Word War I years, a new genre of black American sacred songs known as gospel began to appear. Unlike the anonymous folk spirituals, gospel songs were composed and copyrighted by songwriters like Thomas Dorsey and Reverend William Herbert Brewster, and by the 1930s were being recorded by urban church singers. Some, like Mahalia Jackson, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Ward Singers, turned professional and reached national and international audiences through their tours and recordings. But most gospel singing remained rooted in African American church ritual, and to this day can be heard in black communities throughout the north and south.

Musically, gospel is a blending of spirituals, blues, and the song sermons of the black preacher. Gospel songs are usually organized in a 16- or 32-bar verse/chorus form, often featuring call-and-response singing between a leader and a chorus. Blues tonalities are common, and singers are known for their intensive vocal ornamentations, which include bending and slurring notes, falsetto swoops, and melismas (groups of notes or tones sung across one syllable of a word). Gospel singers often end a song with a prolonged section of improvisation that combines singing, chanting, and shouting in hopes of “bringing down the spirit.” Lyrics are most often New Testament–centered, focusing on the redeeming power of Jesus and the singer’s personal relationship with the Savior.

Although gospel lyrics are strictly religious in nature, gospel music derives much of its sound from blues and jazz. Likewise, gospel music has been a source for various secular styles, including early rock and roll, soul music, and most recently gospel rap. During the Civil Rights era the melodies of old spirituals and gospel songs were used with new lyrics expressing the need to overcome Jim Crow segregation.

The Blues

Blues music was the first significant form of secular music created by African American ex-slaves in the deep South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Growing out of earlier black spirituals, work songs, field hollers, and dance music, the blues addressed the social experiences of the ex-slaves as they struggled to establish themselves in post–Reconstruction southern culture.

Common themes addressed in early country blues songs were conflicts in love relations, loneliness, hardship, poverty, and travel. But it would be a mistake to assume that the blues were exclusively about sorrow—blues celebrated life’s ups and downs, and often reflected a keen sense of ironic wit and a resolve to struggle on against difficult circumstances.

Most of the early recordings of country blues from the 1920s feature a solo male singer like Charlie Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Blake, and Son House, accompanying himself with an acoustic guitar. But blues singers also used banjos, mandolins, fiddles, and harmonicas, and often played in small ensembles that provided dance music at country juke joints. Although blues has been interpreted as a highly individualistic expression because of the solo voice and first person text, the music was often played in social settings where African Americans danced, communed, and solidified their group identity.

Early blues lyrics were built around rhymed couplets that eventually became standardized in a 12-bar (measure) format that featured an AAB structure, with a couplet being repeated twice, and answered by a second couplet:

I woke up this morning,

I was feeling sad and blue. [A]

I woke up the morning,

I was feeling sad and blue. [A]

My sweet gal she left me,

got no one to sing my troubles to. [B]

The tonality is major, most often built around a 12-bar (measure) progression of the I (tonic), IV (subdominant), and V (dominant) chords. The melodic line often features bent and slurred notes, with generous use of the flatted third and seventh tones (known as “blue” notes) of the diatonic scale. The meter is usually duple (4/4), and tempos may vary from a slow drag to a fast boogie.

While the first blues were undoubtedly rural in origin, by the 1920s blues music had made its way to the city. Urban singers like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith recorded and popularized sophisticated, jazz-tinged arrangements of blues in the 1920s, and composers like W. C. Handy incorporated blues forms into popular orchestral pieces like “St. Louis Blues” and “Memphis Blues.” In the post–World War II years the country blues was electrified and transformed into rhythm and blues (R&B) by Chicago-based artists Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield), Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett), and Elmore James, and Memphis bluesman B. B. King. By the mid-1950s southern white singers like Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Buddy Holly were blending rhythm and blues with elements of country music to create the new pop genre of rock and roll.

Rock and Roll

Perhaps America’s most influential contribution to the world of popular music has been the development of rock and roll in the 1950s. Many streams of folk and vernacular music styles, including blues, spirituals, gospel, ballads, hillbilly music, and early jazz, contributed to the evolution of rock and roll (R&R). But it was the convergence of African American rhythm and blues and Anglo American honky-tonk (country) music that led to the emergence of a distinctive new style that would dominate the field of popular music in post–World War II America.

Honky-tonk, often referred to as the voice of the downcast, working-class southern whites, was the dominant form of country music during the 1940s and early 1950s, with Hank Williams being its most famous practitioner. The music featured the tense, nasal vocal style associated with the earlier ballad tradition, accompanied by twangy guitars and fiddles, and lyrics centered on stories of loneliness and broken love relationships. Rhythm and blues was an urbanized version of older country blues that developed in cities like Memphis and Chicago during and immediately after the Second World War. Singers like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and B. B. King shouted and pleaded to their audiences, backed by screaming electric guitars, amplified harmonicas, and a rhythm sections of drums, bass, and piano. The music was loud, aggressive, and sensual, with lyrics boasting of sexual conquest or lamenting failed love.

The earliest rock-and–roll recordings were made by both white and black singers in the mid-1950s. The southern white artists like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Bill Haley were dubbed rockabillies because their sounds were rooted in hillbilly and honky-tonk country styles. Their covers of black rhythm and blues songs like “Rock Around the Clock” (Haley) and “Good Rockin’ Tonight” (Presley) provided some of the first and most powerful examples of how white country and black R&B could blend to form the new style of R&R. From the other side of the racial divide came black R&B singers like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino, who cut their R&B sound with smoother vocals (and in Berry’s case country-influenced guitar licks) to forge a black style of R&R that was close (and at times indistinguishable) from that of their white counterparts.

Thus, R&R was the inevitable result of an interracial musical stew that had been simmering in the southern United States for several centuries. Its appearance in the mid- 1950s was no accident, because this was precisely when independent record companies like Sun (Memphis) and Chess (Chicago) and innovative radio stations like WDIA (Memphis) were beginning to bring black vernacular music to a burgeoning baby boomer audience and the nascent civil rights movements was increasing public awareness of black culture. R&R was a popular style created in the studio and marketed directly for legions of young, predominantly white consumers who, thanks to the relative affluence of the post–World War II years, were in search of new leisure activities.

Musically the earliest R&R recordings were 12-bar blues played in an up-tempo 4/4 meter. Singers, black and white, would sometimes shout and snarl, but were careful to articulate their words in a style smooth enough for their predominantly white audiences to comprehend. The music was backed by a strong, insistent rhythm that accented the second and fourth beat of each measure, creating a sound that was easy to dance to. Rock’s gyrating singers and sensual dancing led many middle-class Americans, black and white, to condemn it as an immoral and corrupting force. When Elvis Presley first appeared on the nationally broadcast TV variety show hosted by Ed Sullivan in 1956, the cameras would only show him from the waist up in order to avoid his sexy moves that had earned him the title “Elvis the Pelvis.”

The lyrics to the most successful early R&R songs centered on teenage romance and adventure, recounting high times cruising in automobiles, dancing at the hop, and falling in and out of love. The lyrics to sexually suggestive R&B songs covered by R&R singers were consciously cleaned up so the music would be less offensive to middle-class (black and white) teens and their parents. Eventually the 12-bar blues form was eclipsed by the verse/chorus structure organized in 8- or 16-bar stanzas. As in earlier American popular songs, the repeated chorus was usually based on a simple but engaging melody (often referred to as the “hook”) that was easy to sing along to.

In the 1960s groups like the Beatles and folk rock singer Bob Dylan transformed R&R by writing more sophisticated lyrics addressing the complexities of love and sexual relations, alienation in Western society, and the utopian search for a new world through drugs and counterculture activities. Both American and British rock groups of the 1960s demonstrated that popular music could provide serious social commentary that had previously been associated with the arenas of modern art and literature and the urban folksong movement. Over the past four decades R&R (often referred to as “rock” to differentiate it from the R&R of the 1950s) has evolved in many directions (art rock, heavy metal, punk, indie), often cross-pollinating with related styles like soul, funk, disco, country, reggae, and most recently hip-hop. At times rock has served as the political voice of angry and alienated youth, and at other times simply as good-time party and dance music.

Rap

Rap is poetry recited rhythmically over musical accompaniment. Rap is part of hip-hop culture, which emerged in the mid-1970s in the Bronx. Graffiti art and break-dance are the other major elements of hip-hop culture. Rap lyrics display clever use of words and rhymes, verbal dexterity, and intricate rhythmic patterning. Rap artists take on different roles and speak from perspectives ranging from comedic to political to dramatic, often narrating stories that reflect or comment on contemporary urban life. Rap artists may be soloists, or members of a rap group (or crew), and may recite in call-and-response format. Rap songs are generally in duple meter at a medium tempo (about 80 to 90 bpm). The musical accompaniment of rap is made up of one or several continuously repeated short phrases, each phrase combining relatively simple rhythmic patterns produced by acoustic and/or synthetic percussion instruments. Other sounds are often added for timbral variety, textural complexity, and melodic/harmonic interest. A bass line provided by electric bass guitar or synthesizer reinforces the meter and defines the tonal center.

Old School Rap (1974-1986)

Old school rap was created by DJs (disc jockeys) and one or more MCs (originally Master of Ceremonies, later Microphone Controller). DJ Kool Herc began this period, providing a portable sound system and spinning records for dances at outdoor parties and small social clubs. He noticed that b-boys and b-girls favored dancing to the “break” in a record, the short section of a song when the band drops out and the percussion continues. Using two copies of the same record on two turntables, Herc was able to make the break repeat continuously, creating the “breakbeat” that became the basic musical structure over which the MC spoke or rapped. DJs Grandmaster Flash, Jazzy Jeff, and Grand Wizard Theodore invented additional turntable techniques: “blending” different records together, scratching (manually moving the record back and forth on the turntable to create rhythmic patterns with scratchy timbres), and mixing in synthetic drum sounds and other effects. An excellent example of turntable techniques is Flash’s The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel (1981). DJs, most importantly Afrika Bambaataa, also promoted hip-hop culture through parties and other events spread by word of mouth and at venues throughout New York City.

At first MCs spoke over records in the Jamaican DJ traditions of toasting (calling out friends’ names) and boasting (touting the superiority of their own sound system and DJ skills). Both traditions became central elements of the assertive and competitive spirit of rap andhip-ho p. Rap drew on other African-American sources for some of its important features: the improvisational verbal skills and call-and-response format of the dozens (an African-American verbal competition trading witty insults), the rhyming aphorisms of heavyweight champion Mohammed Ali (“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee / Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see”), the songs and vocal stylings of the great soul-funk artist James Brown, and The Last Poets, whose members spoke or chanted politically charged poems over drumming.

The first MCs to develop extended lyrical forms by rhyming over break beats were Grandmaster Caz and DJ Hollywood. The interplay of vocal and accompaniment rhythms, rhyme schemes, and phrasing are the main elements of what is known as flow. Old school flow is more regular and less syncopated than later styles. Two-line units (couplets) rhyming at the end of the lines are common during this period, such as, “Pump it up homeboy, just don’t stop / Chef Boy-ar-dee coolin’ on the pot” (The Beastie Boys). Before rap entered into the mainstream entertainment industry, portable cassette players provided a cheap and robust route of dissemination for the music throughout the city. It was the success of Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight, issued on a small independent label in 1979, that brought rap to national attention and gave the genre its name. MC Kurtis Blow’s The Breaks (1980), and Rapture by the pop group Blondie (1981) are also milestones in the early history of rap.

During the first part of the 1980’s the entertainment industry was slow to realize rap’s potential and it was left to entrepreneurs like Russell Simmons to popularize rap and to demonstrate its long-term commercial viability by organizing national hip-hop concert tours and producing hits by many of the most important artists of the period including L.L. Cool J, Slick Rick, and Foxy Brown. Independent films like Wild Style, Beat Street, and Style Wars, introduced hip-hop to a global audience. Rap music videos began to be produced and all-rap radio stations began broadcasting. Independent labels gained ground and rap was incorporated into the established recording and distribution industry. By 1986 hip-hop culture was the most successful popular music in the nation, and rap had developed in three general directions. Pop rap (or party rap) is light, danceable, and often humorous; it quickly became a crossover genre, generating national hits by Salt-N-Pepa (the first successful female rap group), MC Hammer, Vanilla Ice, and many others. Rock rap combines the vocalizations of rap with the sounds and rhythms of rock bands. The hip-hop trio Run-D.M.C. brought rap rock to national prominence with King of Rock (the first hip-hop platinum album, 1985). The Beastie Boys, the first white rap group, appealed to a youth market by smartly combining humor and rebellion in songs from their 1986 debut album Licensed to Ill. Rock rap set the stage for other hybrids that flourished in the 1990’s such as Rage Against the Machine and Linkin Park. Socially conscious rap portrays and comments on the urban ills of poverty, crime, drugs, and racism. The first example is Melle Mel’s The Message (1982), a series of bleak pictures of life and death in the ghetto.

New School Rap

New school rap dates from 1986 when Rakim and DJ Eric B introduced a vocal style that was faster and rhythmically more complex than the simple sing-song couplets of much old school rap. Writers (rap poets/performers) in the new “effusive” style, notably Nas, employed irregular poetic meters, asymmetric phrasing, and intricate rhyme schemes, all of which added depth and complexity to the flow. Much of the new music (and new styles of graffiti and dance) came from the West Coast, and increasingly from the South and Midwest. Hip-hop culture was spreading to Europe and Asia as well.

The accompaniment for rap also became more complex and varied. CD’s largely replaced vinyl records and samplers became commercially available. Producers working with samplers, programmable drum machines, and synthesizers could, with the push of a button, mix and modify sounds imported from a virtually unlimited selection, and so largely replaced DJs as the creators of rap’s musical accompaniment. The New York production team Bomb Squad and producers RZA and DJ Premier layered multiple samples to create dense, harmonically rich textures and grating “out of tune” combinations of sounds, while West Coast producers developed G-funk by using live instrumentation and conventional harmonies associated with funk music.

The year 1988 was an important turning point for rap. The Source, the first magazine devoted to rap and hip-hop, appeared that year, and was soon followed by Vibe, XXL and many others. The first nationally televised rap music videos on Fab Five Freddy’s weekly show “Yo, MTV Raps!” brought hip-hop images and dances to national attention. That same year four new rap genres emerged, partly in response to worsened social conditions in black urban communities: unemployment, drastic cutbacks in education, the crack cocaine epidemic, proliferation of deadly weapons, gang violence, militaristic police tactics, and Draconian drug laws all leading to an explosion in the prison population. Political rap was led by writer KRS-One, with Boogie Down Productions whose album By All Means Necessary explored police corruption, violence in the hip-hop community, and other controversial topics. On the West Coast, N.W.A. were cultivating harsh timbres and a raw angry sound in their nihilistic tales of Los Angeles police violence and gang life in Straight Outta Compton, the first gangsta rap album. Jazz rap, characterized by use of samples from jazz classics and positive, uplifting lyrics was introduced by Gang Starr (DJ Premier and MC Guru) and hip-hop group Stetsasonic. Another answer to West Coast gangsta rap was New York hardcore rap, led by producer Marley Marl whose hip-hop collective The Juicy Crew achieved their breakthrough with the posse track The Symphony. Each genre had important followers. Black nationalism informed the political lyrics

of Public Enemy (led by Chuck D) whose critical and commercial success in 1988-90 proved the crossover appeal of the new wave of socially conscious rap. Houston-based gangsta rap group The Geto Boys combined ultra-violent fantasies with cutting social commentary in a blues-inflected style that came to characterize the “Dirty South” sound in their 1990 debut album. Jazz rap’s Afrocentric lyrics, fashion, and imagery were shared by important new rap artists Queen Latifah and Busta Rhymes. Latifah provided a feminist response to the often misogynist lyrics of male rappers. Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (1993) reclaimed New York’s reputation for cutting-edge hardcore rap. The minimalist production style on the album by this Staten Island group was much imitated through the next decade.

In the 1990’s a style called new jack swing originating with producers Teddy Riley and Puff Daddy integrated R&B into rap and softened rap’s hardcore content while retaining the edge of black street culture. Notorious B.I.G.’s Juicy from Ready to Die (1994) exemplifies the laid-back vocal delivery and slower tempo that characterize new jack. Lil’ Kim’s rap on Gettin’ Money captures the “ghettofabulous” image of the new jack rapper in lyrics that mix gats and six-shooters with Armani and Chanel. The song draws on the iconic American figure of the Mafia don to create metaphors that celebrate materialism and luxury. Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. were the most critically acclaimed and best-selling rappers during the middle of the 1990’s. Shakur was murdered in 1996 and Notorious B.I.G. in 1997. In the eyes of many fans, hip-hop had lost its two greatest artists. Three important figures—Eminem, Jay-Z, and Missy Elliott—led rap into the new millennium.

Jazz

Although most people have heard of jazz, and many recognize it when they hear it, the music is notoriously hard to categorize. There is simply no single description that can account for the vast number of styles and genres that have been placed under the jazz “umbrella.” In fact, some musicians (Duke Ellington, Randy Weston, and others) have avoided using the term altogether, finding the concept too confining. The term itself (and its variant “jass”) did not appear until the 1910s, after jazz was already a well-established idiom, and has been applied to many types of music that most purists would not consider “true” jazz at all, from the novelty piano rags of Zez Confrey in the 1920s to the instrumental pop music of Kenny G in the 1980s and 1990s.

A few general comments can be made about the music, however. We know, first of all, that jazz was a music created primarily by African Americans, and it has deep roots in traditions that go back as far as the African traditions brought by slaves to America during the Middle Passage. Related to this are two dualities that virtually all types of jazz share. These dualities create a vibrant tension in the music that gives jazz much of its power.

Contrary to some popular beliefs, playing jazz is not simply a matter of musicians playing whatever they feel like. Improvisation — creating new music on the spot — is a vital part of almost all jazz traditions (see below), but it nearly always takes place in the context of some larger structure that is planned in advance. This planning can be as simple as deciding who plays what when (the order of the solos, for example) and as complicated as a completely written-out arrangement in which most of the musicians are guided by notes printed on the page. At the very least, musicians will usually decide in advance the tune that will serve as the basis for their improvisations. Perhaps another way to put this is to think of jazz as a very “free” music, one that allows players to explore a variety of means of self-expression, but that at the same time, with freedom comes responsibility. Some type of underlying organization must be in place or the result is chaos.

From the very beginning of jazz’s history, a premium has always been placed on musicians who create their own sound — one that is highly personal and instantly recognizable. Whereas classical musicians will learn the “correct” and “incorrect” ways to play their instruments, for the jazz musician, there is no “proper” way to make a sound. Though some jazz musicians study their instruments in conservatories, many also learn simply by picking up an instrument and figuring out how to make a sound they like, whether or not it has anything to do with “acceptable” technique. The great New Orleans clarinetist and soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet, for example, developed a totally idiosyncratic technique on his instrument — one that would make a classical musician cringe — simply by experimentation, but he had an enormous, rich, and passionate sound that was impossible to duplicate.

Many jazz musicians start their careers by copying another jazz musician outright (legions of saxophonists, for example, have learned Charlie Parker solos by heart) but at some point they must learn to develop their own voice or the music becomes stale. In fact, one of the most damning criticisms a jazz musician can levy at another is to say “he or she is just a Charlie Parker imitator.” At the same time, all great jazz musicians are also good listeners, who take pleasure in what the fellow members of their group are trying to “say” with their instruments, and will often directly respond to ideas that are tossed out as part of an improvisation. In addition, all members of a jazz group pay close attention to how they sound as a group; brilliant solos are only as good as the context in which they are heard. Therefore, in any jazz performance there is always an interesting tension between attempts to sound like a true individual, as well to be a member of the “collective.”

A few more specific features of the jazz tradition can be outlined, and many are related to the dualities discussed above.

- Improvisation. Improvisation of some type is nearly always part of a jazz performance. Even if musicians are reading notes on a page, they can “improvise” through the way they attack or color a note, or the rhythmic impulse they bring to the music. In early jazz musicians often improvised by creating variations on a given melody. As the tradition developed, it became more common to use a chord progression as the basis for entirely new melodies. In more recent jazz traditions, even chords are abandoned and musicians will simply improvise on a scale, a motive, or even just a tonal center. No matter how they improvise, however, most musicians have a set of phrases (called “licks”) that lie easily under their fingers and can be used and reused in a variety of contexts. Charlie Parker, for example, had many signature “licks” that make his style instantly recognizable. In other words, jazz musicians do often play musical lines they have played before, but where they place these lines, and how they play them, is part of the art of improvisation.

- Instrumentation. Certain instruments have become strongly associated with the jazz tradition, mainly because of their tone color and ability to fit into an ensemble or carry a chord structure. And, from its earliest history, there has been a common division of some of the instruments into a subsection known as the “rhythm section” that maintains the rhythmic drive and reiterates the chord progression for other improvising musicians. Ensembles have continued to evolve, however, due to improvements in microphones and recording technology.

- The blues. Nearly all jazz has some connection, even if subtle, with the African American blues tradition, in performance technique, common forms used, and overall musical “feel.” In fact, there are those who would claim that when the music loses its connection to the blues, it ceases to be jazz. (This is the claim often used to prove that Kenny G. is not a jazz musician, even though he plays an instrument associated with jazz — the soprano saxophone — and improvises. His references to blues traditions, when they exist at all, are so stylized that they lack any strong connections to the genuine article.)

- Performance technique. Largely out of the blues tradition comes the jazz player’s proclivity for creating “new” sounds on his or her instrument, and using that instrument in an idiosyncratic way. Often these techniques mirror the use of the voice in various African American traditions; we know, for example, that the bending of pitches and growling or rasping sound often used by jazz musicians mirror black vocal traditions such as the blues, as well as both speech and singing in black church music. Listen to Louis Armstrong as both a vocalist and a trumpeter, and you will note there is little difference between the two. In addition, many people have likened the high pitches (usually out of the normal sound range of an instrument) associated with certain players such as saxophonist John Coltrane to “screams,” even though they may reflect excitement or intensity on the part of the performer, rather than anguish. Such “screams” or “squeaks” are something to be carefully avoided in Western classical music, but many jazz musicians incorporate them into their improvisations intentionally.

- Rhythm. Most jazz performances employ a subtle rhythmic sense that is often called “swing” or “swing feeling” (note this is a different meaning of the term than that used below to describe a style and era of jazz). This “swing feeling” is virtually impossible to define in words (one musician once noted:“if you gotta ask what swing is, you’ll never know”) but it is very different than the subtle pulse of most Western art music, the driving beat of popular music, or the dense polyrhythmic effect of many African traditions. Think of “swing” as a special kind of groove that is unique to jazz; it creates the subtle forward thrust of the music and often is what makes you tap your foot. Especially in the 1930s and 1940s, it was the “swing feeling” mastered by groups such as those led by Count Basie and Benny Goodman that made audiences leave their seats for the dance floor.

The great sweep of jazz’s first century is usually loosely divided into five general periods:

- The music’s origins and the emergence of its early masters.

- The so-called “Swing Era” when the music was the popular music of the United States (and much of the world as well).

- The emergence of bebop in the early 1940s.

- The avant-garde movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

- The “fusion” movement of the 1970s and beyond, in which jazz absorbed influences from a variety of other musical traditions, including rock.

Yet, though some categorization is necessary to make sense of this music’s unique and fascinating path through history, such classifications must be used with care, for a newer style does not necessarily replace an older one. It is possible, in fact, to hear virtually any style of jazz being played in the 21st century; some musicians look back to the work of earlier performers, while others continue to push the music into new realms, often absorbing elements of other genres (including world music and hip-hop) along the way.

Early Jazz

Although New Orleans is often touted as “The Birthplace of Jazz,” it is actually impossible to limit the music’s emergence to a single geographic location. It is clear that vernacular music traditions that would feed into emerging jazz were developing throughout the country at the turn of the 19th century. Yet, New Orleans did supply a distinctive style of jazz, and most of the greatest early practitioners of the music (Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, and others) came from this vibrant cultural melting pot, where blues, classical music, ragtime, church music, and other traditions combined to help create the irresistible, largely improvised music that took the country by storm in the 1920s. The first recordings of jazz were actually made in in New York in 1917 by a white group, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, an ensemble made up of Italian Americans from New Orleans, but the true birth of jazz recording is usually traced to the magnificent recordings made in 1923 by King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band, in which Armstrong played second cornet to Oliver’s lead. Joining the migration of many African Americans to northern cities during the so-called “Great Migration” from the South in the late teens and early 1920s, Oliver, Armstrong, Morton, and many other musicians built careers in Chicago, where the music flourished and some of the early masterpieces by Armstrong and Morton were recorded. Many of these performances include what has become known as “collective improvisation”— everyone appearing to improvise simultaneously in a densely polyphonic texture — though we now know that a considerable amount of planning went into these “improvisations.” Armstrong, however, partly with the encouragement of his wife Lillian Hardin Armstrong, soon emerged as one of the greatest musicians in the country, and since his ground-breaking recordings of the mid and late 1920s, jazz has been largely considered (rightly or wrongly) an art that celebrates the virtuoso soloist.

The Swing Era

In the 1930s, New York City became the center of jazz activity, as it has remained to the present day. In addition, partly because of the huge demand for dance music (the country was in the midst of the Depression and dance — along with movies — provided escape from the dismal realities of daily life) and the sizeable venues into which jazz musicians were booked, jazz bands became larger, often with entire sections of reed and brass instruments. In addition, the saxophone — considered largely a joke instrument in the 1920s — emerged as the jazz instrument par excellence (perhaps because of its versatility and similarity to the human voice). This was the era of the jazz big band, and of groups such as those led by Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Count Basie. It was also the heyday of the jazz arranger, who took on the responsibility of laying out specific parts for members of the band (often in notation) as well as incorporating improvisation, for collective music-making was no longer feasible in a group of 15 or more musicians. Many of the era’s greatest soloists — saxophonists Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Johnny Hodges and Ben Webster, clarinetists Goodman and Artie Shaw, trumpeters Roy Eldridge, Red Allen and Cootie Williams (as well as Armstrong, of course) — played with these big bands. Big band jazz swept the nation, becoming the most popular type of dance music on the scene, and resulting in the creation of thousands of records. In addition, radio, which had begun to have an impact on American culture in the 1920s, exploded into one of the country’s most important media.

Bebop

Largely because of financial hardships brought on by World War II, the popularity and economic feasibility of big band jazz began to wane in the 1940s. But a host of young musicians had already begun experimenting with new approaches to the music, whether out of boredom, a sense that African American musicians were being exploited in big bands, or simply the natural tendency of creative minds to evolve. These developments went largely undocumented, as they often took place in late-night, informal jam sessions. In addition, in the early 1940s the Musician’s Union called for a ban on all recordings (in protest over the fact that musicians were not being recompensed for the airplay of their records), so the brewing sea change in jazz went largely unrecorded. Yet, by 1945 trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and alto saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, along with pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell and drummers Max Roach and Kenny Clarke, had essentially redefined jazz. Though their music, which became known as “bebop,” remained firmly rooted in past jazz traditions, they promoted a return to small-ensemble music, and greatly expanded jazz ’s harmonic, rhythmic and melodic possibilities. They also seemed to suggest that jazz be taken more seriously as an art form, rather than dance music (though Gillespie once commented, when a listener complained that he couldn’t dance to bebop, “YOU can’t dance to it!”). This music of 1940s created the foundation for nearly all modern jazz, and saw an important separation between the music and social dancing. In addition, the popularity of jazz began to be supplanted by the emerging idioms of R&B and R&R.

The Avant-Garde

Jazz musicians continued to explore the terrain opened up by Parker and Gillespie and others during the 1950s. Some created music even farther distant from the popular and accessible music of the 1930s, while others tried to counteract what they saw as the more “cerebral” aspects of bebop by playing music more deeply rooted in the blues and gospel. In 1959, a group led by saxophonist and composer Ornette Coleman (which had been playing to small and largely hostile audiences on the West Coast) took their inventive styles to New York. Coleman’s music often did away entirely with usual ideas of improvising on a melody or chord progression. The work of Coleman and his compatriots is often referred to as “Free Jazz” (the name of an album Coleman recorded in 1960) but the idiom was not quite as loose as the name suggests, with often a tonal center or motive providing an important organizing principle, and close dialogue between the various musicians a crucial feature of the music’s overall effect. Nevertheless, Coleman’s music, which also revolutionized the roles of the various instruments in the ensemble, was highly controversial, as was his own edgy, often harsh instrumental tone and idiosyncratic technique, which some saw as evidence of poor musical training. Some musicians rejected the new styles entirely, while others — most notably, perhaps, saxophonist John Coltrane — were strongly influenced by them. Even trumpeter Miles Davis, though reportedly not a fan of avant-garde jazz, seems to have incorporated some of its traits in the work of his famous 1960s quintet, which featured saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bassist Ron Carter, drummer Tony Williams, and pianist Herbie Hancock.

Fusion and Jazz-Rock

In 1969 Miles Davis made the highly controversial move of including electric instruments on his In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew albums, adding as well rhythmic structures aligned with rock and soul. Many accused Davis of “selling out”— of trying to pander to popular music tastes of the time — but though Davis was certainly interested in expanding his dwindling audience, he also heard fascinating possibilities in the work of Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown, and Jimi Hendrix. Many alumni from Miles’s “electric” groups went on to form fusion bands of their own — keyboardist Chick Corea with Return to Forever, Wayne Shorter and keyboardist Joe Zawinul with Weather Report, guitarist John McLaughlin with The Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Herbie Hancock with a group that produced the hugely popular Headhunters album in 1973. Though many critics complained that their music “wasn’t jazz,” it did maintain improvisation and connections with the blues that had always been a part of the jazz tradition.

The 1980s and Beyond

The last three decades have seen the extension of many of jazz history’s streams, as well as the promotion of jazz as an art worthy of academic discourse. In the 1980s, New Orleans-born Wynton Marsalis, himself an alumnus of drummer Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, emerged as one of the most important spokespersons for the music. Though widely criticized by many as musically conservative, he has done much for the promotion of jazz worldwide, especially in his role as director of Lincoln Center’s jazz program. As it always has, the art of jazz continues to evolve and reflect changing political and economic climates, as well as absorbing other music that emerges in the now-digital age.

Source: D. Cohen, Music – Its Language, History and Culture is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Douglas Cohen (Brooklyn College Library and Academic IT) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform. Davis, CA: LibreTexts

The Blues: Made in America.

Scholars generally acknowledge that enslaved Africans brought their musical traditions to the United States. Historical records mention that some slave Page 70 →traders required Africans to bring their musical instruments with them. On slave ships traders used whips to force captives to sing and dance—a form of shipboard exercise that entertained the traders and “aired” the captives to prevent disease.3 Once in the United States, enslaved Africans continued to make music on African and European musical instruments. Many firsthand accounts from colonial America describe group dancing and singing on Sundays, as well as songs to accompany manual labor.4

After the Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, some slaveholders moved west and south, taking enslaved people with them to cotton plantations in Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Louisiana, and eventually Texas. Some of the musical instruments we associate with those parts of the rural southern United States closely resemble African traditional instruments. The banjo appears to be a version of the long-necked lutes played by itinerant minstrels in the West Sudanic Belt, the transitional savannah area between the Sahara Desert and Equatorial Africa that runs from Senegal and The Gambia through Mali, northern Ghana, Burkina Faso, and northern Nigeria. By contrast, one-stringed instruments, played with a slider against the string, are traditional in the music of central Africa: they are an antecedent of the slide guitar tradition in the southern United States. Another kind of one-stringed instrument is the “mouth bow,” which is plucked or strummed while held against the mouth. This instrument, played in the Appalachian and Ozark regions of the United States, is part of the musical traditions of Angola, Namibia, and southern East Africa.5 The presence of these instruments offers tangible evidence that Africans brought their own ways of music-making to the Americas.

Because slave owners bought and transported slaves at will, though, Africans typically could not stay together in family and community groups that maintained these traditions. The extent to which African ethnic groups were able to maintain contact among themselves in the Americas is debated by historians: there is some evidence that ethnic clusters persisted in some places, but most scholars describe the African experience in the Americas as one of profound dislocation for families and communities.6 Considering this disruption, some scholars have wondered about the possibility of survivals or retentions from African music—that is, whether some traits persisted from the traditional musics that Africans brought with them.7 In contrast, the music scholar Kofi Agawu argues that these terms imply too much passivity; rather, Africans and people of African descent actively guarded and preserved their musical heritage.8

What is certain is that Africans continued to develop and adapt their traditions in the Americas; they also initiated new musical traditions. The blues are an exemplary case. The blues are a tradition of solo singing, developed by African Americans in the United States in the mid- to late 1800s, that gives the effect of highly personal expression. Early blues often described hard work and sorrow, but they also treated broken relationships, money problems, and other topics—sometimes seriously and sometimes with a wry sense of humor. The lyrics are cast in the first person: “I’m leaving this morning with my clothes in my hand . . .”; “I didn’t think my baby would treat me this way. . . .” The first-person lyric does not mean the blues are autobiographical; rather, the singer creates a speaking persona and a vivid situation with which the listener can identify.9 Most melodic phrases start at a relatively high pitch and descend. In addition, the singer might use wavy or inexact intonation, producing an expressive and highly variable sound that may resemble a complaint, a wail, even a provocation. In early blues there might be just one accompanying instrument, often played by the singer: guitar, banjo, fiddle, mandolin, harmonica, or piano. As blues gained in popularity and record companies began issuing recordings, that simple accompaniment was often replaced with a small band.

The poetic form of the blues is a three-line verse: the first two lines have the same words, and then the third line is a conclusion with new words:

Lord, I’m a hard workin’ woman, and I work hard all the time

Lord, I’m a hard workin’ woman, and I work hard all the time

But it seem like my baby, Lord, he is dissatisfied.10

This verse form maps onto a musical structure, the “12-bar blues”: each line consists of four bars (units), each of which comprises four beats (time-units felt as pulses). This form can be repeated, bent, broken, or ignored as the musician wishes. The tempo is slow, and the rhythm has a characteristic “swing,” giving the listener the sense that there is an underlying pattern of long and short notes on each beat. The overall texture is not complicated. Often the instrument drops out, or simply keeps the beat while the singer sings one phrase, and then comes in with more interesting material after that phrase. This kind of musical back-and-forth is known as a pattern of call and response.11 Mississippi Matilda Powell’s “Hard Workin’ Woman” (example 3.1) is a blues composition that exemplifies all these features.

Link: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9853855.cmp.33

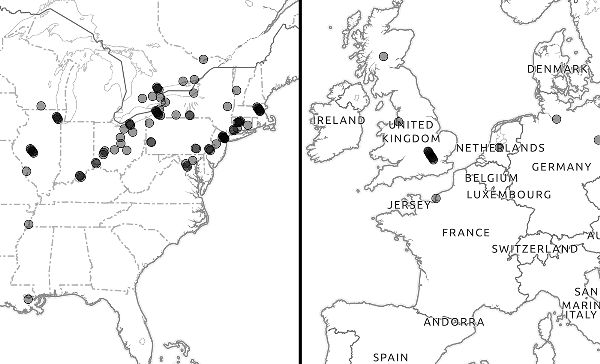

Gerhard Kubik is an ethnographer—that is, he seeks to record and analyze the practices of particular groups of people. For many years he has tried to understand the connection between African music and the African American blues tradition in the southern United States. Kubik traveled through Africa and made numerous field recordings; he then compared specific elements of those field recordings to the earliest existing recordings of the blues. Kubik was careful to note that there are limitations in this method: by comparing recordings made decades apart and continents away, one cannot determine a “family tree” for the blues. Music was not routinely recorded until the 20th century, so there is no way for us to hear precisely how the blues tradition developed during its early years. And certainly the recordings Kubik made in the 1960s cannot be “ancestors” of blues recordings from the 1920s! Rather, Kubik tried to identify characteristic elements of musical traditions—traits that might be preserved over time—that would suggest a kinship between those traditions. Like a family resemblance to a distant cousin, these traits hint at a relationship; but as we will see, there is also much in the blues that reflects their distinctly American origins.

Kubik’s research suggests that musical traits from two different parts of Africa contributed to the blues. One is an ancient lamenting song style from West Africa that was associated with work rhythms, which Kubik calls the “ancient Nigritic” style. These songs would be accompanied by the repetitive motions and sounds of manual labor, like the sound of the stones used for grinding grain. Kubik recorded example 3.2, sung by a person he identified only as “a Tikar woman,” in 1964 in central Cameroon.

Link: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9853855.cmp.34

The grinding tool that accompanies the song produces a “swinging” rhythm. The singer’s melody begins high and descends with each phrase, and the phrases are of roughly equal length. The words of this song, like those of typical early blues, are a lament and a work song: “If you don’t work you cannot Page 73 →eat. I am crying about my fate and my life.”12 Kubik identifies these features as survivals within the blues style. He compares the example from the Tikar woman in Cameroon with the blues singing of Mississippi Matilda Powell (example 3.1). Powell’s thin, breathy vocal quality also resembles that of the Tikar woman.

The other style Kubik identifies as a possible cousin of the blues is an Arabic-Islamic song style that developed among the people of the West Sudanic Belt, particularly the Hausa people of Nigeria and Niger. Unlike the ancient Nigritic style, the Arabic-Islamic song style was urban and cosmopolitan: it flourished around major cities and courts. This kind of music was made by a single person, accompanying himself on an instrument. As the singer was an entertainer who would move from place to place, this tradition consisted of solo songs that were not connected to community music-making. An example offered by Kubik is the song “Gogé,” performed by Adamou Meigogué Garoua, recorded in northern Cameroon in 1964 (example 3.3).

Link: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9853855.cmp.35

The distinctively raspy vocal style of this example sounds vehement and sometimes exclamatory, the words declaimed theatrically. Most of the phrases descend in pitch, and the singer’s voice often slides between pitches or moves quickly among ornamental notes. The combination of voice with instrument is also distinctive: during the sung phrase the fiddle is silent, but between phrases the fiddle comments with melodies of its own in a call-and-response pattern. We also hear in this song the characteristic “blue” notes (bent or pitch-altered notes) associated with blues.

Kubik compares Garoua’s song with a blues by Big Joe Williams, “Stack O’Dollars” (example 3.4), recorded in 1935 in Chicago.

Link: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9853855.cmp.36

As in the Garoua example, Williams uses his voice to make many different qualities of sound. Sometimes he speaks in a raspy voice; sometimes his melodyPage 74 → reaches up to become a wail. Throughout, he bends notes, glides between notes, and adds ornaments. The call and response between the singer and instruments is present here, too. For these reasons Kubik identifies a link between these elements of the Arabic-Islamic song style and the African American blues.

In short, Kubik finds it likely that musical traits from different groups of people, and different parts of Africa, contributed to the blues tradition in the United States. But the Arabic-Islamic and ancient Nigritic song styles were not like stable “ingredients” that simply mixed together to form the blues, nor were they handed down only among people who belonged to the ethnic groups from which these styles came. That is, blues were not a “heritage” music in this genealogical sense. During the slave trade, family and ethnic groups suffered disruption and dislocation. The migration of slave owners and the sale of enslaved people to distant regions meant that members of different African ethnic groups were mixed together and dispersed widely among European American communities. The blues were not cultivated only among West Sudanic or West African ethnic groups in the United States. So how did these elements of song traditions take root, or become localized, in their new environment?

In Kubik’s view the prominence of certain traits in blues is not explained by who brought these traits to the United States (heritage). Rather, these traits became widespread because they were useful and attractive to black people in the particular environment of the South in the 1800s; that is, this music spread as a tradition, passed from person to person.13 Musicians can learn both songs and techniques fairly quickly: when they hear something they like, they may imitate it and adopt it as their own. Kubik thinks there was a kind of selection process; for example, musical traditions involving drums were frequently suppressed by slave owners, so traditions without drums flourished. That blues could be performed by one person with any instrument that came to hand made it an inexpensive and mobile musical form that was hard to take away. Unlike louder forms of group singing and dancing, the blues were less likely to attract unwanted attention in an oppressive and controlled environment. Blues singers could use the themes of suffering, overwork, and loneliness derived from the ancient Nigritic style to describe their experiences and to speak for their communities. Furthermore, the 1890s saw the rise of Jim Crow laws, which limited economic and social opportunities for African Americans; but because slaveholders had exploited black people for entertainment as well as work, white Americans remained willing to accept African Americans as entertainers.14 In all these ways the blues had expressive and practical advantages.

Appropriation, Authenticity, and the Blues

The blues are much more than the sum of these African traits. Many aspects of the American context, including various audiences and commercial markets for the blues, were vital in shaping the history and content of this music. When black blues musicians traveled to perform in tent shows and vaudeville theaters (1890s–1920s), they found an audience of mixed ethnicities with an appetite for popular song. Soon white singers picked up this style of singing and the three-line form of the blues song. Composers of popular songs, many of them Jewish American, wrote blues and published them as sheet music (1910s). Many of these popular songs—some labeled as “blues,” some just incorporating aspects of the blues—were issued on commercial recordings (1920s).

In the 1930s and 1940s, folklorists—some sponsored by the US government—went looking for southern folklore and “rediscovered” the rural blues, which by then seemed utterly different from the widely known commercial forms of blues. Elvis Presley (1950s) and the popular singers of the British Invasion (1960s) not only took African American blues singers as their models but also recorded their songs, often without attributing them to the original songwriters.15 By the late 1960s the blues were recognized around the world as distinctively belonging to the United States. They were used in US public relations abroad and widely imitated.16 We have already seen in chapter 2 an instance in which the musical practice of a minority group becomes a symbol and a point of pride for the nation at large. (Recall that the “Hungarian” music for which Hungary is most famous is Romani music.) To extend Kubik’s line of thinking: the blues spread among people of many ethnicities because the style and themes of this music appealed to many musicians and audiences.

Yet, in the face of persistent social and economic inequality, one might wonder whether this kind of appropriation can happen on fair terms. Appropriation means taking something as one’s own. Musical “taking” is, of course, a special case: if someone adopts a musical style or idea, the person from whom it was adopted can still play the music that has been taken. For this reason musical appropriation is sometimes called borrowing, which has a less negative connotation. A more neutral-sounding term for the spreading of music is diffusion—an intermingling of substances resulting from the random motion and circulation of molecules, as in chemistry. As the metaphor of diffusion involves no human actors at all, just the movement of music from one group to another, this idea seems to attribute the movement of music to a Page 76 →natural process—like talking about globalization as a “flow” without saying who caused that flow. But appropriation is a purposeful choice, and a personal one: as we saw in the case of Liszt (chapter 2), the act of taking music as one’s own reflects the taker’s values and biases.

If we want to think about it in neutrally descriptive terms, we might say that the circulation of ideas is merely what has happened, and still happens, in the ebb and flow of music-making. Musicians have long taken sounds and ideas from others, repurposing or altering music to suit their own purposes. But appropriation can also mean theft. Cultural appropriation occurs when a member of a group that holds power takes intellectual property, artifacts, knowledge, or forms of expression from a group of people who have less power.17 Most definitions of cultural appropriation assume that “cultural” groups and their musical practices have clear and firm boundaries. They do not: music may be made differently even by members of the same group, and group allegiances are often hard to define. But people use the idea of cultural appropriation to address a real problem: if the powerful take music from the less powerful, what are the consequences? To put it bluntly: is this appropriation more like a complimentary form of imitation or more like a colonial extraction of resources?

One form of harm that can come about through cultural appropriation is that powerful people profit more from the music than do the less powerful people who made the music first. In the early days of the blues African American performers did earn money through in-person performance and recordings. Still, their earnings were modest. Recording and publishing companies often cheated musicians who lacked access to expert advice about contract and copyright law. Many media outlets preferred to play recordings by white musicians, further limiting black musicians’ opportunities to profit.18 During and after the 1960s, rock bands such as the Rolling Stones, Cream, and the Allman Brothers certainly reaped far greater monetary rewards from the blues than did the African American blues musicians whose songs they played. At the same time, the blues revival that spread the blues among Americans of other ethnicities increased professional opportunities for African Americans. Some musicians of this generation, such as B. B. King and Buddy Guy, attained considerable wealth and prestige, as well as a place in the spotlight. As the black blues musician Muddy Waters reportedly said of the Rolling Stones, “They stole my music but they gave me my name.”19

Cultural appropriation can also make practitioners of the appropriated music feel that they have been misrepresented. The revivalists’ attraction to the Page 77 →blues was based in part on insulting exoticist stereotypes about African Americans and their lives.20 In a 1998 history Leon Litwack wrote that “the men and women who played and sang the blues were mostly poor, propertyless, disreputable itinerants, many of them illiterate, many of them loners, many of them living on the edge.”21 This account describes African Americans as hapless, mysterious, and utterly different from other Americans who might encounter their music. These stereotypes emerge from long-standing categories of racist thinking that have been difficult to unseat. Historically, the advocates of segregation had justified their position by claiming that African Americans were weak, dependent, and incapable of progress, effectively relegating them to the enforced boundaries that slavery had created. These habits of thought persisted even as many white Americans embraced the blues, and they remain a key part of the image of the blues.

Instead of seeing the blues as an art form requiring expertise, some observers have viewed the blues as the natural product of African Americans’ mysterious lifestyle. Eric Clapton, the lead guitarist of Cream, noted that it had taken him “a great deal of studying and discipline” to learn the blues, whereas “for a black guy from Mississippi, it seems to be what they do when they open their mouth—without even thinking.”22 The stereotype operating here makes a hard distinction between folkloric music (handed down by tradition, eternally the same) and commercial music (sold in a marketplace, constantly changing). As we saw in chapter 1, the idea of the “modern” had been used to draw distinctions between non-Europeans and Europeans, and between the savage and the civilized.23 Clapton’s statement set his own creativity apart from that of African Americans, failing to acknowledge the individual creative effort of black blues artists.

Some people have argued that cultural appropriation is harmful because they want to preserve the authentic musical practice—for instance, recovering the blues as they were long ago rather than allowing for changes in the tradition. Authenticity is perceived closeness to an original source; judgments of authenticity are made with the aim of recovering that real or imaginary original. People who seek authentic blues take pleasure in a folk experience they have imagined for themselves as rural, untouched by commerce, and laden with suffering: they hope to find a true point of origin where the music first sprang into existence. Yet this argument is based less on historical facts than on present-day values, which emphasize distinctions between folk and commercial music and between origins and current uses. Authenticity is not a property of the blues; rather, it is a story that people tell about the music and Page 78 →its makers, a story that emphasizes heritage and the difference between “them” and “us.”24

In seeking authenticity, people often treat “cultures” as clearly delimited from each other, and they look for a source that is identifiably from only one group, not mixed or “hybrid.” The problem with this kind of thinking is that reality is more complicated. As best we can know it from the limited documentation that survives, the history of the blues does not support a clear distinction between folk and commercial music. Far from untouched by commerce, African American artists took advantage of opportunities to make money through music. Oral histories of the rural blues suggest that some blues musicians traveled from place to place to earn a living as entertainers, acquiring new material and making innovations in their performances along the way.25 The blues became known to the wider public in the 1900s and 1910s, as African American musicians performed the blues and other music professionally in theaters and circus sideshows. Blues musicians heard, and sometimes imitated, the vaudeville performances.26 When the blues were “discovered” by record companies—and of course one can hardly call it a discovery, as the music was already flourishing—African American performers willingly recorded their music for commercial markets.27 These recordings, in turn, fostered a new generation of blues musicians in the South, who learned to play from the recordings instead of from local musicians.28 In one way or another most musicians tailor their music to the demands of audiences, and African American musicians are no exception.29 Here we see a limitation of Kubik’s theory or of any theory that tries to define a thing by going back to its origins. Some elements of African music came together in the blues, but the context of traveling shows and commercialism in the United States was also an essential factor in the music’s development.

The mistaken focus on authenticity at the expense of other musical values reifies music—that is, makes it into an object rather than an activity. When blues became not just a manner of performance, but also a folk artifact to be recorded for posterity or a musical form to be copied, it became more like an object to its borrowers, losing the flexibility of live performance and changeable tradition.30 Once that happens, there is a risk that all performances will be measured against that “original” version. Holding the original as the highest standard disincentivizes creative development of the tradition.

Focusing on authenticity can also assign to music-makers a rigid set of group characteristics that differentiate them from other groups. The belief that all members of a certain group have particular inherent attributes is called Page 79 →essentialism: it is a way of making stereotypes seem truthful by saying they are a permanent part of the people they represent. The blues were especially attractive to white musicians in the 1960s who wanted to seem oppositional to the social status quo. But by emphasizing the authenticity of the tradition, they relegated African Americans to being part of history rather than part of the present day, as Clapton did. They essentialized African Americans as the unchanging folk source of the music and named themselves as the innovators.

Claims about authenticity are not only produced by white people who want to reify the blues. They have also been used by people who want to protect African American ownership of the blues tradition. This line of thinking has sometimes been called strategic essentialism: a disempowered people’s temporary use of stereotypes about themselves to promote their own interests—in this case, to guard a valued heritage against a specific act of appropriation.31 In the early 1960s, a volatile period in the civil rights movement, the critic Amiri Baraka wrote a searing critique titled “The Great Music Robbery” in which he addressed white appropriations of African American music. He objected because white musicians were earning so much profit and praise for playing black music but also because the blues represented specific African American experiences. Baraka went so far as to call the idea of a white blues singer a “violent contradiction of terms”: not because the blues were a genetic inheritance of black people but because the common experience of discrimination, reflected in the blues, bound black people together as a group.32 The absorption of black music into American music, explained Baraka, changed the meaning of black music and even felt like erasure of black people and their experiences. “There can be no inclusion as ‘Americans’ without full equality, and no legitimate disappearance of black music into the covering sobriquet ‘American,’ without consistent recognition of the history, tradition, and current needs of the black majority, its culture, and its creations.”33

At the same time, though, saying that black people are fundamentally different from other Americans reinforces that social separateness and the stereotypes that support it. The music scholar Ronald Radano has argued that Baraka’s criticism essentializes African Americans by assuming they all share similar origins and experiences. Telling the story of black music as if it were entirely separate from white music not only misrepresents history but also reinforces a false belief in fundamental racial differences—and this belief can then be used to justify continuing discrimination.34 Baraka did recognize the danger of essentialism: in a different essay he emphasized that committed musicians of any color could learn the “attitudes that produced the music as a Page 80 →profound expression of human feelings.”35 This statement means that African American music is an open tradition in which people of various ethnic origins might learn to participate, if they are willing to try to understand black musicians’ perspectives and experiences.

Thus, the objections to cultural appropriation boil down to economic exploitation and disrespectful representation.36 One could try to respond by discouraging appropriation. Yet people who use the charge of cultural appropriation as an effort to prevent traditions from mixing can also cause harm, perpetuating essentialist stereotypes. Thinking of the blues as an unchanging essence encourages white audiences to ignore African Americans’ further development of that tradition—or of other traditions. Worse, thinking of African Americans as people who only produce blues or spirituals unjustly limits their artistic freedom. In the words of the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, “talk of authenticity now just amounts to telling other people what they ought to value in their own traditions.”37 Musical appropriation across lines of social power seems generally to have this ambivalent quality: it can cause real harm to real people, yet trying to prevent appropriation can also cause trouble by encouraging inflexible and stereotypical thinking about groups and differences. This dilemma is built into life in the United States because of the violent and unequal circumstances by which the nation developed. The particulars of any musical borrowing among peoples in the United States may reinforce that violence, or work against it, or try to find a way past it; but it is always there to be grappled with.38

The Spiritual: Mutual Influence and Assimilation