4.4 Visual Arts

Arts: Italian Renaissance

How to Recognize Italian Renaissance Art

Video URL: https://youtu.be/6YiL9MNyGKE?si=z12OTwG8uO_1oGto

Understanding Linear Perspective

Video URL: https://youtu.be/eOksHhQ8TLM?si=XbT7E2pElNqrMYLr

Masaccio’s Holy Trinity and Linear Perspective

Video URL: https://youtu.be/mdd7LhVx00o?si=Y_0XjPlBrJ99gwEW

Benozzo Gozzoli, The Medici Palace Chapel frescoes

Inside the Medici Palace, just off the palace’s central courtyard at street-level, is the Medici Chapel (or Magi Chapel). Completed in the mid-fifteenth century, this intimate room still dazzles its visitors with its vividly painted frescoes and gold leaf which is in stark contrast to the palace’s rather modest exterior. One can easily imagine the glittering effect of flickering candlelight in the opulent space of the Medici Chapel.

The Medici family was a wealthy and powerful Florentine family, whose fortune was built on their banking industry. The Medici Bank was initiated in the late 14th century under Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, but the family’s economic power ultimately helped them garner increased political power, and they became the rulers of Florence (and later Tuscany) for much of the fifteenth through early eighteenth centuries. While the patron of the Palazzo, Cosimo de’ Medici (“il Vecchio”), wanted his family home to have an austere, geometric public face (so as not to be perceived as ostentatious), the family’s wealth and influence was strategically displayed throughout the interior, including in the Medici Chapel. This balance reflects Cosimo’s calculated efforts to maintain power and favor in Florence while avoiding conspicuous outward displays of the family’s wealth. This was especially important in the fifteenth century when power in Florence was constantly oscillating between the Medici and the Florentine Republic. So, it was beneficial for the Medici to avoid appearing too pretentious and greedy in their public displays of wealth.

The small Medici Chapel was meant to function as a space of private worship for the family. For the space’s fresco decoration, the Medici chose the painter Benozzo Gozzoli, who had trained under the Florentine Fra Angelico (known for his frescoes in the monastery of San Marco, a decorative program which was also funded by Cosimo il Vecchio).

Such private spaces for worship—whether in a public setting, such as a local church, or in one’s family home—were quite common for rulers and the wealthy in early modern Italy. However, papal permission for the construction of a private family chapel inside a residence was required, and the Medici had obtained this through Pope Martin V by 1442.

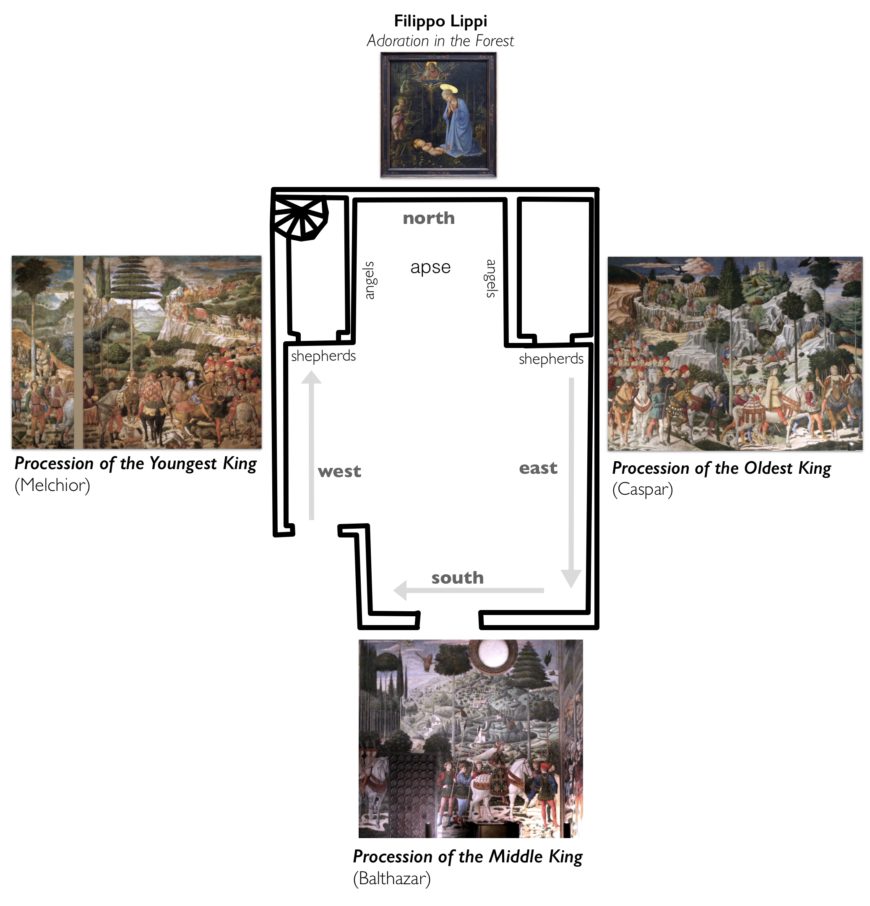

A feast for the eyes, Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes cover every wall of the small chapel, enveloping the viewer from all sides. Said to have been painted in about 150 days in 1459, the theme centers around three biblical kings from far-reaching lands, commonly known as the Magi or wisemen. According to Christian tradition, these men visited the Christ child shortly after his birth and brought expensive and exotic gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. The three kings and their large entourage are painted with rich detail as they complete their long journeys.

Their procession extends across the east, south, and west walls of the nearly perfectly square space, leading towards the north wall which incorporates an unusual square apse (they are most often hemispherical). With Lippi’s altarpiece at its center (today a copy of the original work), the decoration of the apse denotes a separate realm, where frescoed angels appear to worship on either side of the Adoration in the Forest altarpiece.

The altarpiece and the frescoes were conceived of as a united program, functioning together to produce an overall effect more powerful and spiritually moving than its constituent parts. Throughout the chapel, Gozzoli alternated between buon fresco and fresco secco, and in the final stages of the project, areas of gold leaf were applied. The gold leaf adds an opulence to the imagery and its use recalls what is now referred to as the International Gothic style, long associated with princely patronage.

The gold-leaf applied throughout the composition helped to create a shimmering, ethereal experience when viewed in candlelight. The incorporation of this expensive material, as well as the use of costly pigments like ultramarine blue, made from lapis lazuli, cast the Medici in the role of the Magi, “giving” Christ an expensive gift by way of paying for the construction and decoration of this space. This effect is reinforced by the inclusion of portraits of Medici family members in the guise of the Magi and their entourage (explored below). Spotted throughout the frescoed walls are orange trees, a common Medici symbol reflective of the palle (balls) of their coat of arms, lest any future visitors question the patronage of the space.

Each of the three walls showing the long journey of the Magi focuses on one of the three kings: Melchior (the eldest king), Balthazar, and Caspar (the youngest). Interestingly, visitors to the chapel do not see the more commonly represented end of their journey, the moment when the three kings have actually reached the Holy Family and they adore the newborn Christ Child, such as we see in Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi altarpiece. The patron of Gentile da Fabriano’s work, Palla Strozzi, was part of a rival Florentine banking family. In this work, the Strozzi family also associated themselves with the generous Magi. Their Adoration, however, was visible to the general public, located in the family’s chapel in the church of Santa Trinità. Contrasting more common period depictions of the Magi having reached their destination (the newborn Christ child), in Gozzoli’s private Medici Chapel frescoes, the Magi are frozen in a perpetual and unfulfilled journey across the walls of the room. Instead, it was the flesh and blood members of the Medici family who worshipped before the altar in this space who were meant to realize the goal of reaching and adoring the Holy Family.

This kind of role-play was typical of many patrons, including the Medici, who frequently liked to imagine themselves as similar to these wealthy kings of the biblical past who adorned Christ with gifts. Another example of the Medici associating themselves with the Magi is found in Cosimo il Vecchio’s personal, private cell in the monastery of San Marco, also located in Florence. This room was used by Cosimo as a meditative escape, and he chose to have it decorated with a scene of the Magi giving gifts to the newborn Christ child. This image of the adoration of the Magi in his own private monastic retreat allowed Cosimo to reflect on important Christian stories while simultaneously considering his own family’s “similarities” to these three kings. Notably, this particular cell in San Marco was decorated by both Fra Angelico and one of his star pupils—Benozzo Gozzoli himself.

In the Medici Chapel, accompanying the Magi and their entourage on each of the three walls, recognizable portraits of members of the Medici family can be found riding along with each group.

A long caravan of figures leads several camels, donkeys, and horses, whose backs all appear to be loaded with goods, if not carrying people. Behind this caravan, the oldest king, Melchior, is accompanied by a group of contemporary figures, many of whom are recognizable allies of the Medici. Dressed in blue and lingering in a princely group just in front of Melchior, a figure proposed as a portrait of the young Giuliano de’ Medici rides his horse while accompanied by two exotic cats. This young man looks out towards the viewer, inviting them to contemplate this important journey. Here, Gozzoli includes his own portrait as one of the many pilgrims who travel alongside Melchior.

The second king, Balthazar, continues the procession behind Melchior. Bearded, somewhat darker-skinned, and wearing a rich green and gold embroidered gown, Balthazar’s appearance indicates the vast global range from which the three kings came.

It is important to note that the relative age of the three Magi is changeable in works of the period. For example, Balthazar is often identified as the youngest king, and is increasingly said to hail from the African continent. However, Gozzoli’s youngest king is Caspar. Taking on the role of Caspar is a young Lorenzo (il Magnifico) de’ Medici, soon to become one of the greatest Medici rulers of Florence’s history. He rides a white horse while leading the last part of the procession, another large group of lay people. The young Lorenzo may have been pictured as Caspar because his birthday fell on the Feast of Caspar, January 1.

Next in line in the group that follows Lorenzo/Caspar is Lorenzo’s father, Piero, and then his grandfather (the original patron of the Palazzo Medici), Cosimo il Vecchio. The huge group behind them includes recognizable depictions of many other important leaders of the period with close associations to the Medici, such as Sigismondo Malatesta (Lord of Rimini) and Galeazzo Maria Sforza (Duke of Milan), along with illustrious Florentines, like the humanists Marsilio Ficino and the Pulci brothers, important members of various Florentine guilds, and none other than Gozzoli himself.

Yes, the artist included his own portrait twice, just in case you missed him the first time. He looks directly out at the viewer in both instances. Here at the end of the procession, Gozzoli’s red hat is inscribed in gold leaf with the words, “Opus Benotii” (the work of Benozzo), the only legible text found on anyone’s attire. By incorporating these two self-portraits into the scene, Gozzoli made sure that he would be remembered long after his death, and even more importantly, that he would be remembered in connection with the powerful Medici family.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Black bowman (detail), east wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Copyright: Dr. Rebecca Howard, “Benozzo Gozzoli, The Medici Palace Chapel frescoes,” in Smarthistory, April 11, 2022, accessed June 13, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/benozzo-gozzoli-magi-chapel-medici-palace-frescoes/.

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus

Video URL: https://youtu.be/K6PBfbkMzFU?si=afZbfmnqvEIb1x6I

Donatello, David

Donatello’s hero is remarkable for numerous reasons, not least of which is the sculpture’s all’antica (“in the manner of the antique”) form. In some ways the work epitomizes new trends in early renaissance art: it is the earliest known freestanding nude sculpture since antiquity. Furthermore, it is cast in bronze, a costly medium not generally used for large-scale freestanding sculpture in the medieval era—it would take a Medici to afford such an expense. Although it is a difficult sculpture to date, it was probably finished by the early 1450s. [1] And while no documentation survives for the commission, primary sources confirm that it was displayed in the Medici courtyard by 1469 and was thus likely a Medici commission from the start.

The subject of this statue is David, the future king and hero of the Hebrew Bible, who as a youth slayed the giant Goliath and liberated his people (the Israelites) from the tyranny of the Philistines. In Donatello’s sculpture, David’s immaturity is unquestionable: his nude body is that of an adolescent and is sharply contrasted with the heavy beard and maturity of Goliath, whose severed head is at his feet. David’s vulnerability is emphasized by the stone he clasps in his left hand, a reminder that though he holds a sword, he brought down his massive foe with a simple sling-shot. The message here is clear: David triumphed not through physical power, but through the grace of God.

While the biblical account (1 Samuel 17) does note that David chose not to face Goliath wearing the armor offered to him by his father, nowhere does it state that he removed his clothes completely. In all earlier images of David, including an earlier marble version carved by Donatello himself, David is clothed. The choice to depict David as completely nude, except for a shepherd’s hat adorned with laurels of victory and elaborate sandals, was unprecedented.

David’s nudity serves several functions. Exposing his youthful (weak) body overtly reinforces the miraculous nature of his triumph. David is literally bared before God and the viewing public, victorious through God’s will alone. Standing in contrapposto and displaying accurate anatomy, the sculpture also demonstrates the growing interest in humanism, an intellectual movement that looked to the Greco-Roman past for inspiration.

When seen from behind, the sex of Donatello’s David is ambiguous. In this patriarchal world, this androgyny may have been yet another reminder of his ineptness for battle. Renaissance Italy was male dominated: power passed from father to son and both religious and secular authorities insisted upon the superiority of men and masculinity. The sexual ambiguity, even effeminacy, of Donatello’s David helps emphasize that the youth’s victory could only be achieved by God’s intervention. When viewed from up close—an experience likely only available to privileged visitors to the palazzo—this androgynous nudity is further complicated by erotic undertones. Goliath’s helmet is adorned by a scene of Eros (Love) riding a chariot and a feather delicately caresses David’s inner thigh, both elements suggest themes of erotic love.Scholars have tied this eroticism to Florentine obsession with youthful male beauty, an interest that is evidenced in numerous works of art and even brought the ire of Florentine preachers who called it a sinful perversion. The fact that the sword, hat, and sandals are of contemporary Florentine fashion and not that of biblical times, suggests a connection to these renaissance preoccupations. Of course, David’s beauty, his desirability, was also part of the biblical tradition. He is referred to as “most beautiful among the sons of men” in Psalm 44 and the name “David” was translated to mean “beloved.” The message would have been clear to renaissance Florentines: Donatello’s David embodies desirability, he is beloved by God and this is the source of his victory.

By the time the bronze David was created, the hero was already a symbol of the Florentine Republic. Donatello’s marble David had been on display in front of the Palazzo dei Priori since 1416 against a backdrop of lilies, an insignia of Florence. By placing this civic hero in their private courtyard, the Medici claimed for themselves this state symbol, making David a Medici emblem as well as a Florentine one. For a family of supposedly private citizens of a republican state who were all but absolute rulers in practice, the Medici had good reason to associate themselves with David’s anti-tyrannical symbolism. Cosimo and his family likely wanted all visitors to their palace to regard them—like David—as defenders of liberty.

Copyright: Dr. Heather Graham, “Donatello, David,” in Smarthistory, August 10, 2021, accessed June 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/donatello-david/.

Donatello, Saint George

Video URL: https://youtu.be/UAQsYoYZfxs?si=tW4E9AAgckru3A7C

Leonardo and His Drawings

Born near the town of Vinci in 1452, Leonardo trained in the Florentine workshop of Andrea Verrocchio (1435-88). His first masterpiece was the unfinished Adoration of the Magi (1481, Uffizi, Florence). In 1481-2 he travelled to Milan to work for the Duke, where he painted the Virgin of the Rocks (Musée du Louvre, Paris-a later version exists in the National Gallery, London) and the Last Supper (1495-7; Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie (Refectory), Milan). In 1499 he travelled to Mantua and Venice, arriving back in Florence in 1500.

In 1503 he began the cartoon of the Battle of Anghiari with its scenes of ferocious fighting for the wall in the Great Council Chamber of the Palazzo Vecchio, but this work was never completed. He returned to Milan in 1506 for seven years and in 1513 he moved to Rome. The French king, Francis I, invited him to his court and about 1516, Leonardo settled in the manor of Cloux, near Amboise in the Loire valley. Leonardo died there in 1519.

Leonardo is arguably the greatest draughtsman in Western art. He was technically superb in whichever medium he used: silverpoint, pen and ink, black and particularly red chalks. Driven by his scientific curiosity, he studied the world around him in minutest detail, making botanical and anatomical studies. In his drawings and paintings he created figures which lived, breathed, moved and gave expression to their emotions.

This is one of a number of sheets of drawings by Leonardo in which he designed instruments of war. He drew them while working for Ludovico Sforza, duke of Milan (1494–99). Under each drawing in ink and brown wash, Leonardo has written words of explanation in his characteristic reversed writing (that is it needs to be read in a mirror).

At the top of the sheet is a chariot with scythes on all sides. Below it Leonardo has written: “when this travels through your men, you will wish to raise the shafts of the scythes so that you will not injure anyone on your side.” At lower left is an upturned armored car without its roof, showing “the way the car is arranged inside” with the line “eight men operate it and the same men turn the car and pursue the enemy.” At lower right, the same tank-like vehicle is shown moving and firing its guns, with the line below: “this is good for breaking the ranks, but you will want to follow it up.” At the far right is a more conventional weapon of the time, a large pike or halberd, perhaps more ceremonial than practical.

Leonardo’s fertile imagination and scientific knowledge are here combined in the creation of war machines for his warlike patron. It is highly unlikely, however, that any of these machines were ever made or used in contemporary warfare. Indeed, as Leonardo himself wrote in his Notebooks, such new weapons were often as dangerous to their users as to the enemy.

Copyright: The British Museum, “Leonardo and his drawings,” in Smarthistory, March 1, 2017, accessed June 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/leonardo-and-his-drawings/.

Leonardo, Last Supper

Video URL: https://youtu.be/XCg7o4onjxs?si=LNBUPllTlNcYeOj0

Leonardo, Mona Lisa

Video URL: https://youtu.be/B06PK4yZwvY

The Mona Lisa was originally this type of portrait, but over time its meaning has shifted and it has become an icon of the Renaissance—perhaps the most recognized painting in the world. The Mona Lisa is a likely a portrait of the wife of a Florentine merchant. For some reason however, the portrait was never delivered to its patron, and Leonardo kept it with him when he went to work for Francis I, the King of France.

Piero della Francesca’s Portrait of Battista Sforza is typical of portraits during the Early Renaissance (before Leonardo); figures were often painted in strict profile, and cut off at the bust. Often the figure was posed in front of a birds-eye view of a landscape.With Leonardo’s portrait, the face is nearly frontal, the shoulders are turned three-quarters toward the viewer, and the hands are included in the image. Leonardo uses his characteristic sfumato—a smokey haziness—to soften outlines and create an atmospheric effect around the figure. When a figure is in profile, we have no real sense of who she is, and there is no sense of engagement. With the face turned toward us, however, we get a sense of the personality of the sitter.

Copyright: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Leonardo, Mona Lisa,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed June 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/leonardo-mona-lisa/.

Michelangelo, David

Video URL: https://youtu.be/QdlP8ai8trw?si=D5K4OOsGNT6WMjHI

Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

Video URL: https://youtu.be/PEE3B8Fsuc0?si=pwQpwKpVoLyMQAqC

Michelangelo began to work on the frescoes for Pope Julius II in 1508, replacing a blue ceiling dotted with stars. Originally, the pope asked Michelangelo to paint the ceiling with a geometric ornament, and place the twelve apostles in spandrels around the decoration. Michelangelo proposed instead to paint the Old Testament scenes now found on the vault, divided by the fictive architecture that he uses to organize the composition.

![Diagram of the subjects of the Sistine Chapel [1] (photo: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/1280px-Sistine_Chapel_ceiling_diagram.svg-870x468.png)

The subject of the frescoes

The narrative begins at the altar and is divided into three sections. In the first three paintings, Michelangelo tells the story of The Creation of the Heavens and Earth; this is followed by The Creation of Adam and Eve and the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden; finally is the story of Noah and the Great Flood.

Ignudi, or nude youths, sit in fictive architecture around these frescoes, and they are accompanied by prophets and sibyls (ancient seers who, according to tradition, foretold the coming of Christ) in the spandrels. In the four corners of the room, in the pendentives, one finds scenes depicting the Salvation of Israel.

Although the most famous of these frescoes is without a doubt, The Creation of Adam, reproductions of which have become ubiquitous in modern culture for its dramatic positioning of the two monumental figures reaching towards each other, not all of the frescoes are painted in this style. In fact, the first frescoes Michelangelo painted contain multiple figures, much smaller in size, engaged in complex narratives. This can best be exemplified by his painting of The Deluge.

In this fresco, Michelangelo has used the physical space of the water and the sky to separate four distinct parts of the narrative. On the right side of the painting, a cluster of people seeks sanctuary from the rain under a makeshift shelter. On the left, even more people climb up the side of a mountain to escape the rising water. Centrally, a small boat is about to capsize because of the unending downpour. And in the background, a team of men work on building the arc—the only hope of salvation.

In 1510, Michelangelo took a yearlong break from painting the Sistine Chapel. The frescoes painted after this break are characteristically different from the ones he painted before it, and are emblematic of what we think of when we envision the Sistine Chapel paintings. These are the paintings, like The Creation of Adam, where the narratives have been pared down to only the essential figures depicted on a monumental scale. Because of these changes, Michelangelo is able to convey a strong sense of emotionality that can be perceived from the floor of the chapel. Indeed, the imposing figure of God in the three frescoes illustrating the separation of darkness from light and the creation of the heavens and the earth radiates power throughout his body, and his dramatic gesticulations help to tell the story of Genesis without the addition of extraneous detail.

This new monumentality can also be felt in the figures of the sibyls and prophets in the spandrels surrounding the vault, which some believe are all based on the Belvedere Torso, an ancient sculpture that was then, and remains, in the Vatican’s collection. One of the most celebrated of these figures is the Delphic Sibyl.

The overall circular composition of the body, which echoes the contours of her fictive architectural setting, adds to the sense of the sculptural weight of the figure.

Her arms are powerful, the heft of her body imposing, and both her left elbow and knee come into the viewer’s space. At the same time, Michelangelo imbued the Delphic Sibyl with grace and harmony of proportion, and her watchful expression, as well as the position of the left arm and right hand, is reminiscent of the artist’s David.

The Libyan Sibyl is also exemplary. Although she is in a contorted position that would be nearly impossible for an actual person to hold, Michelangelo nonetheless executes her with a sprezzatura (a deceptive ease) that will become typical of the Mannerists who closely modelled their work on his.

Copyright: Christine Zappella, “Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed June 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/michelangelo-ceiling-of-the-sistine-chapel/.

Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel

Video URL: https://youtu.be/c2MuTvQM61Y?si=8p-IforEyARZO38_

The Last Judgment was one of the first art works Paul III commissioned upon his election to the papacy in 1534. The church he inherited was in crisis; the Sack of Rome (1527) was still a recent memory. Paul sought to address not only the many abuses that had sparked the Protestant Reformation, but also to affirm the legitimacy of the Catholic Church and the orthodoxy of its doctrines (including the institution of the papacy). The visual arts would play a key role in his agenda, beginning with the message he directed to his inner circle by commissioning the Last Judgment.

The decorative program of the Sistine Chapel encapsulates the history of salvation. It begins with God’s creation of the world and his covenant with the people of Israel (represented in the Old Testament scenes on the ceiling and south wall) and continues with the earthly life of Christ (on the north wall). The addition of the Last Judgment completed the narrative. The papal court, representatives of the earthly church, participated in this narrative; it filled the gap between Christ’s life and his Second Coming.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment is among the most powerful renditions of this moment in the history of Christian art. Over 300 muscular figures, in an infinite variety of dynamic poses, fill the wall to its edges. Unlike the scenes on the walls and the ceiling, the Last Judgment is not bound by a painted border. It is all encompassing and expands beyond the viewer’s field of vision. Unlike other sacred narratives, which portray events of the past, this one implicates the viewer. It has yet to happen and when it does, the viewer will be among those whose fate is determined.

Despite the density of figures, the composition is clearly organized into tears and quadrants, with subgroups and meaningful pairings that facilitate the fresco’s legibility. As a whole, it rises on the left and descends on the right, recalling the scales used for the weighing of souls in many depictions of the Last Judgment.

Christ is the fulcrum of this complex composition. A powerful, muscular figure, he steps forward in a twisting gesture that sets in motion the final sorting of souls (the damned on his left, and the blessed on his right). Nestled under his raised arm is the Virgin Mary. Michelangelo changed her pose from one of open-armed pleading on humanity’s behalf seen in a preparatory drawing, to one of acquiescence to Christ’s judgment. The time for intercession is over. Judgment has been passed.

Directly below Christ a group of wingless angels (left), their cheeks puffed with effort, sound the trumpets that call the dead to rise, while two others hold open the books recording the deeds of the resurrected. The angel with the book of the damned emphatically angles its down to show the damned that their fate is justly based on their misdeeds.

On the lower left of the composition (Christ’s right), the dead emerge from their graves, shedding their burial shrouds. Some rise up effortlessly, drawn by an invisible force, while others are assisted by herculean angels, one of whom lifts a pair of souls that cling to a strand of rosary beads. This detail reaffirms a doctrine contested by the Protestants: that prayer and good works, and not just faith and divine grace, play a role in determining one’s fate in the afterlife. Directly below, a risen body is caught in violent tug of war, pulled on one end by two angels and on the other by a horned demon who has escaped through a crevice in the central mound. This breach in the earth provides a glimpse of the fires of hell.

On the right of the composition (Christ’s left), demons drag the damned to hell, while angels beat down those who struggle to escape their fate (image above). One soul is both pummeled by an angel and dragged by a demon, headfirst; a money bag and two keys’ dangles from his chest. His is the sin of avarice. Another soul—exemplifying the sin of pride—dares to fight back, arrogantly contesting divine judgment, while a third (at the far right) is pulled by his scrotum (his sin was lust). These sins were specifically singled out in sermons delivered to the papal court.

Especially prominent are St. John Baptist and St. Peter who flank Christ to the left and right and share his massive proportions. John, the last prophet, is identifiable by the camel pelt that covers his groin and dangles behind his legs; and, Peter, the first pope, is identified by the keys he returns to Christ. His role as the keeper of the keys to the kingdom of heaven has ended. This gesture was a vivid reminder to the pope that his reign as Christ’s vicar was temporary—in the end, he too will answer to Christ.

In the lunettes (semi-circular spaces) at the top right and left, angels display the instruments of Christ’s Passion, thus connecting this triumphal moment to Christ’s sacrificial death. This portion of the wall projects one foot forward, making it visible to the priest at the altar below as he commemorates Christ’s sacrifice in the liturgy of the Eucharist.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, however, was not painted for an unlearned, lay audience. To the contrary, it was designed for a very specific, elite and erudite audience. This audience would understand and appreciate his figural style and iconographic innovations. They would recognize, for example, that his inclusion of Charon and Minos was inspired by Dante’s Inferno, a text Michelangelo greatly admired. They would see in the youthful face of Christ his reference to the Apollo Belvedere, an ancient Greek Hellenistic sculpture in the papal collection lauded for its ideal beauty. Thus, Michelangelo glosses the identity of Christ as the “Sun of Righteousness” (Malachi 4:2). In contrast to its limited audience in the sixteenth century, now the Last Judgment is see by thousands of tourists daily. However, during papal conclaves it becomes once again a powerful reminder to the College of Cardinals of their place in the story of salvation, as they gather to elect Christ’s earthly vicar (the next Pope)—the person who will be responsible for shepherding the faithful into the community of the elect.

Copyright: Dr. Esperança Camara, “Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel,” in Smarthistory, November 28, 2015, accessed June 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/michelangelo-last-judgment/.

Raphael, School of Athens

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Smd-q44ysoM?si=jUzg5an6RHp4_4zz

What is Mannerism?

The term “mannerism” is not easily defined. It has been used to designate art that is overtly artificial, often ambiguous, and conspicuously sophisticated. However, these are by no means the only stylistic traits associated with this designation. Mannerist imagery frequently pushes the boundaries of fantasy and imagination with artists looking to art, rather than nature, as a model, as Parmigianino was clearly doing in his painting. Mannerism is therefore a confusing term, subject to radically different interpretations. When the term was first widely used in the 17th century, it was intended as a pejorative label. It was used to negatively characterize Italian renaissance art created between 1520 and 1600 that was seen by these later audiences as overly stylized and tasteless, a debased departure from the classicism of Raphael and the high renaissance. With the rise of expressionism and abstraction in the 20th century, such negative views of this generation of artists subsided. Today, the English term “mannerism” is used to broadly designate 16th-century art throughout Europe (and even in places like the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries) that is conspicuously artificial, often emotionally provocative, and designed to impress.

In sixteenth-century Italy, where what we now call mannerism is first evident, the term “mannerism” did not exist. What we do find is “maniera,” a term rooted in the word mano (hand). It was used in a straight forward way by contemporaries to simply designate style. The styles that the word maniera was used to describe were as varied as way the word style might be used today. Audrey Hepburn had style. So did David Bowie.

Maniera was also used in the 16th century to suggest “stylishness” itself, a self-conscious, artificial artistry that at times privileged fantasy over reality. Artists displaying maniera may consciously exploit their technical skill but ideally did so with seeming effortlessness. Artistic departures from visual reality were intended to demonstrate invention and refinement, learning and grace. One way to understand mannerism, popularized by late 20th-century scholars, is to think of it as the “stylish-style.” Rather than seeing such images as breaking with renaissance visual developments, scholars now recognize mannerist imagery as continuing those explorations in new ways. While the artworks might seem to diverge from classical forms, these artists did actually invent new ways of engaging with the ancient past. One of the most influential artworks for mannerist artists was the Hellenistic sculpture of Laocoön and his sons, whose twisting, contorted bodies appealed to a variety of artists of this time, including the Burgundian artist Juan de Juni (who worked in Spain), Domenicos Theotokopoulos (known as El Greco), Alonso Berruguete, and Francesco Primaticcio. Berruguete frequently adapted aspects of the Laocoön in his sculpture to heighten the emotional expressiveness of his saintly figures, such as we find in his Abraham and Isaac.

Why do these elegant explorations take place after 1520? While there is no easy answer for the style’s emergence at this time, historical and religious developments, the tastes of powerful patrons, and the rising social status of the artist may all be key factors. Mannerism first developed in central Italy in the cities of Rome and Florence and it quickly spread. The reasons are many. The early and mid-16th century was a period of enormous social, economic, and political change witnessing the spread of Protestantism and the wars of religion that followed. The rise of capitalism and absolutism, colonization and exploitation of new lands and peoples, and new developments in the science of anatomy and optics also add to the era’s complexity. Some have attributed the new stylistic explorations of the period to a general neurosis resulting from this shifting context. The new contorted and exaggerated forms are deliberately unbalanced like the 16th century itself.

Mannerist art has been associated with the tastes of aristocratic patrons, particularly those within court circles where displays of wealth and appreciation for beautiful things helped cultivate an elite persona. The self-conscious artifice and deliberate complexity of these works would have appealed to patrons who were familiar with recent artistic developments and eager to show off their knowledge and good taste. The general rise in the status of the artist—particularly in central Italy where mannerism first developed over the course of the renaissance, may also have contributed to a rising taste in art that reflected an artist’s individual style. Previously, artists were regarded as humble craftsmen, practitioners of the “mechanical arts.” By the 1520s—thanks in part to high renaissance artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, Albrecht Dürer and others—visual artists could claim status as practitioners of a “liberal art,” placing them alongside scholars, poets, and other humanists. The stylistically specific creations of individual visual artists were increasingly valued as precious records of their individual ingenuity and intellect, it meant something to own a “Dürer” or a “Titian.” The pronounced stylishness of mannerist imagery unmistakably marked these works as creations of a unique maker.

The ambiguity of mannerism and often sensuous treatment of figures proved problematic for some. The Reformation brought with it a new scrutiny of religious images. The Augustinian monk Martin Luther and other Protestant leaders were concerned that images could mislead or be treated as idols. While the Catholic Church never wavered in its commitment to the validity of images as tools for religious practice, the style of religious art did become an issue. At the Council of Trent (1545–1563), a series of meetings intended to solidify Catholic doctrine and strengthen the threatened church, it was declared that religious images must be clear, unambiguous, and lead viewers to faithful contemplation. Art should be for celebrating and instructing in the faith, not for showcasing artistic skill. The sensuosity, ambiguity, and conspicuous artistry of mannerism was not to be tolerated in sacred art.

This call for conservatism in art on the part of the Catholic Counter Reformation, the movement behind the Council of Trent, did not bring an end to mannerist explorations. The style continued in new ways and across the global Catholic landscape. Devout Catholics, such as the Duke of Florence, Cosimo I de’Medici (who was eager to garner the Pope’s approval in his quest to become Grand Duke of Tuscany), continued to patronize mannerist forms in paint and stone—and even tapestries. El Greco, an artist who is thought to almost perfectly embody the Counter-Reformation Church’s desire to produce emotionally affective religious works, borrowed a great deal from mannerism. In fact, El Greco’s work demonstrates that mannerism extends beyond the sixteenth century, attesting once again to the ways in which visual strategies ebbed and flowed differently in various parts of the world.

Copyright: Smarthistory – Mannerism, an introduction

Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck

Video URL: https://youtu.be/suIUUGdNyWk?si=c5_Ub_ygDCBhUrAI

El Greco, View of Toledo

Landscape paintings are often meant to document the look of a particular time in a particular place, to freeze a single moment and preserve it for eternity. El Greco’s View of Toledo does not do that. Although the large church is placed in the correct place in the city, El Greco changed the locations of several other buildings, proving that documentation was not the artist’s primary concern. Rather than telling us what Toledo looked like, here, El Greco communicates what the city feels like. Toledo becomes the means through which the artist expresses an interior psychological state, and perhaps, a view about the nature of man’s relationship with the divine.

Using typically dark, moody colors, El Greco presented the Spanish city of Toledo at the top of a rolling hill. The city itself takes up only a little space in the center of the painting. The landscape and sky dominate. This is not just any sky. El Greco’s clouds are about to crack open and unleash a storm on the city. The buildings themselves seem to crawl across the painting, and curving lines throughout the hill give the impression that the vista is moving, that it might actually be alive.

In El Greco’s Toledo, something is about to happen, and it probably isn’t going to be good.

To understand how radical this painting is, we have to weigh a few historical circumstances. First, El Greco was painting in Counter Reformation Spain, where religious dictates based on the Council of Trent (which ended in 1563), banned the landscape as a suitable subject for painting. Although the church was his primary patron, the artist broke with that convention, and because of this, View of Toledo has been called the first Spanish landscape. More impressively, cityscapes never existed anywhere in the sixteenth century. El Greco may literally have invented the genre. Some art historians found this so unsettling that they had suggested that, because El Greco often included views of Toledo in the backgrounds of his religious paintings and portraits, View of Toledo may have actually been cut from the background of a larger painting. However, we now know that this is not true.

Although El Greco, “the Greek,” is most usually known as a Spanish painter, he was born Domenikos Theotokopouolos in Crete in 1541, and spent much of his life in Italy. He was trained in the tradition of Byzantine icon paintings in either Crete or Venice, where many Cretans had settled, and by the 1560s was painting in Titian’s workshop. In the 1570s he went to Rome. Although El Greco was well reputed in Italy, he failed to secure any commissions in the city, and was convinced by a Spaniard to move to Toledo, where he spent the next forty years of his life, and where he died in 1614.

Why did the city of Toledo inspired El Greco to paint such a powerful picture of the city? In Spain, El Greco failed to find favor with the king, and instead worked for the Catholic Church. If he was not raised in the faith, he almost certainly would have had to convert to Catholicism. In the 1500s, Spain’s Catholic Church had undergone huge transformations. The century started with the Spanish Inquisition, in which non-Catholics were hunted out, tried, tortured, and often, killed. At the same time, people, like Saint Theresa of Avilla and Saint Ignatius of Loyola (both Spanish), were preaching that, through prayer, one could be directly inspired by God, and they claimed to have frequent visions in which God spoke to them. Because of their beliefs, even these saints came under the scrutiny of the Inquisition, although they were eventually acquitted. Spain’s brand of Catholicism, compared to Italy’s, was mystical and based on personal experience.

This mysticism is reflected in El Greco’s View of Toledo. Almost entirely subsumed by the landscape, the city seems to be at the direct mercy of God. This is not a forgiving God, but rather a wrathful one, as in the Old Testament. Toledo is undergoing a reckoning. At the same time, the landscape transcends this religious reading. It becomes reflective of the inner conflict of each human being, the feeling that making one’s way in the world is a harrowing endeavor.

Copyright: Christine Zappella, “El Greco, View of Toledo,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed June 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/el-greco-view-of-toledo/.

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the Head of Medusa

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Q1j-gPKAcDA?si=Lg1HnoQ_-F6Y9blD

Michelangelo, Pietà

Video URL: https://youtu.be/JbWGusfynCw?si=YW3DhC-EB23FBrBJ