2.5 Supplemental Readings

Supplemental Reading Topics

Palace of Knossos

There aren’t many places in the world like Knossos. Situated 6km south of the sea, on the north central coast of Crete, several things make this archaeological site important: its great antiquity (it is 9,000 years old), many different cultural layers (Neolithic through Byzantine), its size (nearly 10 square Km) and its great popularity (the second most visited archaeological site in Greece after the Acropolis at Athens). Aside from these, however, Knossos is also exceptional because of its role in the writing of history. It is the type site for all of Minoan archaeology, was one of the first large-scale scientific excavations in Europe, and contains some of the most contentious restorations in the ancient Mediterranean. Because of all this, Knossos is a critical part of multiple discourses in the history and historiography of the ancient world. We can’t stop talking about Knossos.

A palace?

Bronze Age Knossos is traditionally called a palace, a description used by its most famous excavator, Sir Arthur Evans. Indeed, when Evans, just three weeks after beginning his work at the site, discovered a grandly paved and painted room with a large stone chair set in the wall he believed he had found the throne of Minos and the kings of Crete. This royal interpretation of the site of Knossos stuck. Although it is now clear that the role of Knossos was at least as religious and economic as it was political, it is still just called a palace.

Early Knossos

The site of Knossos was first inhabited around 7000 B.C.E. and was one of the earliest Neolithic sites in the Mediterranean, settled at a time when pottery had yet to be invented. It continued to be a well-populated site for successive Neolithic eras, one literally building upon another, eventually creating one of the only tell sites of the Aegean, nearly 100 meters above sea level. Unfortunately, not a lot is known about Neolithic Knossos as the Bronze Age inhabitants entirely covered over its remains with their own structures. However, limited excavations show that it was one of the oldest farming villages in Europe which had connections to even earlier Mesolithic inhabitants elsewhere on the island.

Before the palace

The end of the 4th millennium B.C.E. is the beginning of the early Bronze Age at Knossos, a time when the inhabitants learned how to combine tin and copper to make bronze tools and weapons, far more durable than their stone predecessors. Although the palace structure is yet to come, already the buildings on the site have a north-south orientation, as the palace eventually will. Moreover, it appears that ceremonial activity was already common at this time, evidenced by so many specially made and decorated drinking cups. Approximately 1,000 years later, around the end of the 3rd millennium B.C.E., the first large-scale buildings were built at Knossos. The nature and shape of these structures are very difficult to ascertain because the later palace largely obscures them, but already the outline of the large (49 x 27m) rectangular open central court is established.

Standing in the central court today

Protopalatial or Old Palace Knossos

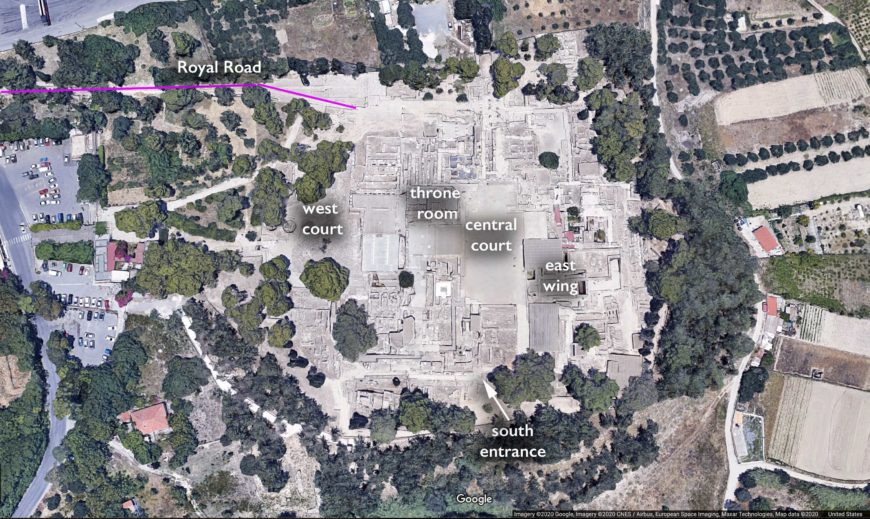

Approximately two hundred years later, at the start of the 2nd millennium (around 1950–1800 B.C.E.) the outline and dimensions of the palace of Knossos emerges and begins what is called the Protopalatial or Old Palace period. The two most distinctive features of this earliest version of Knossos are the long, monumental, cut ashlar stone of the palace’s west façade and the central court, now squared off in the corners and paved. This court functioned as a grand performance space. In this period, a wide paved road, which Evans named the Royal Road, is built. The road connects Knossos to the adjacent town to the west. An entrance system of raised walkways is also built at this time.

It is clear that, like contemporary ancient Near Eastern temples, storage was an important aspect of Protopalatial Knossos. Long thin storage rooms to the west of the central court are built at this time. In addition, sunk into the open court to the west of the palace were large, deep, circular pits lined with plastered stone, called Kouloures, which archaeologist believe stored grain.

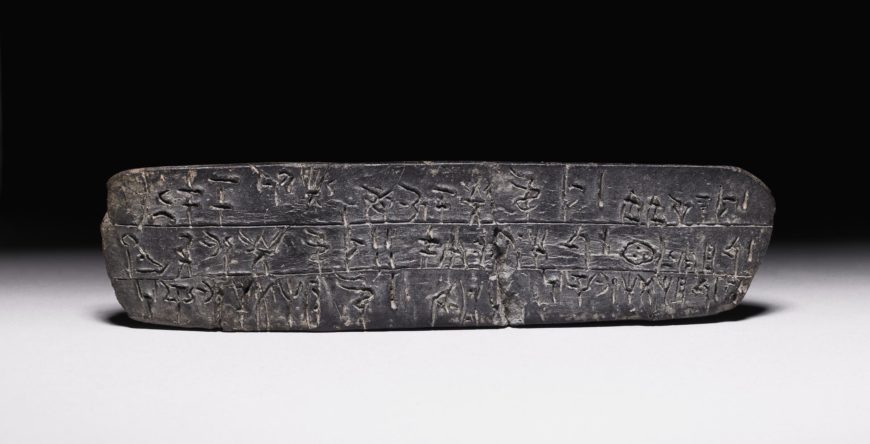

Protopalatial Knossos stored more that raw materials, it also produced finished goods. There is evidence of seal stone carving, weaving, and pottery production (especially Kamares Ware) and likely gold working as well. In this busy place, a written script, Cretan Hieroglyphic, was used to keep records, written on clay tablets and nodules which were attached to containers of goods. As of yet, the language this script recorded has not been translated.

Neopalatial or New Palace Knossos

Around 1700 B.C.E. major renovations are undertaken at Knossos, likely the result of a destructive event, possibly an earthquake. These renovations mark the beginning of the Neopalatial or New Palace period and result in the most characteristic elements of Knossos: the West Court is paved (made by filling in the Protopalatial Kouloures) to be used for public ceremonies, the monumental south entrance (or South Propylaeum) is added to impress visitors.

The Throne Room with its lustral basin or light well is built to comfortably accommodate the leadership of the palace, and the elegant spaces of the East Wing or Domestic Quarter are constructed, where Evans believed the queen of Knossos passed her time.

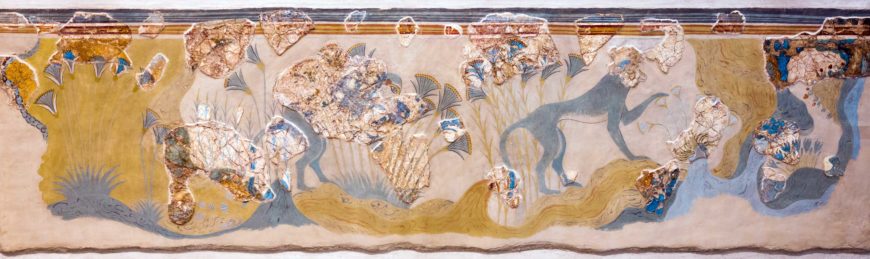

These new spaces were replete with innovative architectural details including colonnaded staircases, light wells, pier and door partitions, and wall and floor paintings. This was a grand era for painting at Knossos. There were beautiful scenes of the natural world, such as in the Blue Monkey or Partridge Frieze frescoes, as well as miniature scale works such as the Grandstand Fresco, which seems to represent group performances in the West Court.

The monumental North Entrance passage was rebuilt in the Neopalatial period and decorated with a relief wall painting of a raging bull, an image which becomes emblematic of Knossos and Minoan Crete. Pottery production reaches new heights, most famously in the delightful marine style, which some archaeologists believe is a reflection of a Minoan thalassocracy (sea power).

Innovation in the Neopalatial period extends to writing as well: a new script, in addition to Cretan Hieroglyphic, is used at Neopalatial Knossos, Linear A. Although this script also remains largely unreadable, it is clear that it was used for accounting and administration, noting the movement of materials and people between the palace and sites across the island. It also reflects the way in which Knossos and a number of other smaller sites which look very similar to Knossos, and are also called palaces (Malia, Phaistos, Zakros, Monastiraki, Petras, Chania and Galatas) were a focal point for much of the population and labour on Crete at the time. This palatial network not only connected Cretan communities but also maintained trading ties with the Eastern Mediterranean.

Postpalatial or Final Palatial Knossos

There are signs that the palace suffered a series of destructions around 1450 B.C.E., at the same time that there are widespread destructions and abandonment of Minoan sites all over Crete. These events begin what is called the Postpalatial or Final Palatial period, which lasts approximately 150 years. Knossos is rebuilt after these destructions but differently. For instance, no more lavish limestone ashlar masonry was cut for the exterior of the palace and new interior walls were erected to change the flow of movement, seemingly to cut off certain areas, such as the West magazines (storage areas), presumably for security. Most importantly, the Throne Room was redesigned in this era to include the griffins seen in the archaeological reconstruction and possibly for the installation of the throne itself.

Much of the palace interior was repainted in this Postpalatial era and this Postpalatial era and this includes many of the most famous wall paintings from Knossos: the bull leaping or Toreador fresco, the Procession fresco, and the Camp Stool fresco. Pottery produced at Postpalatial Knossos is called Palace Style and is based on Neopalatial predecessors but with a quirky kind of stylization which renders subjects less naturalistic and more pattern-like. Some new pottery shapes are created which appear in imitation of mainland Mycenaean pieces.

Postpalatial Knossos is still a place of very complex administration as is described by the hundreds of clay tablets discovered. However, the Linear A script is no longer used; it is replaced by Linear B, which can be read, and records a very early form of Classical Greek, the language of the contemporary Mycenaeans of mainland Greece. The social order described in these tablets is that of a Wanax as the leader of Knossos and a deep administration concerned with land tenure, religious activities, and a massive textile industry which employed over 700 shepherds harvesting between 50–75 tons of raw wool, woven by nearly 1,000 workers, men, women, and children, capable of producing some 20,000 individual textile pieces.Knossos was clearly a prosperous city in this period and this can also be seen through a new type of burial at the site: warrior graves. These, sometimes extravagantly constructed, tombs of men and women feature a range of fighting weapons such as swords and thrusting daggers, as well as valuable metal vessels and elegant pottery. These sorts of very rich, well-constructed graves are a tradition which is associated with the mainland of Greece.

Cretan and mainland cultures

A lot about Postpalatial Knossos has a distinct Mycenaean flavor and this fact has led many archaeologists to conclude that the destructions at the beginning of the period were actually the Mycenaeans invading the island. However, many Minoan elements remain in Postpalatial culture, and obvious signs of warfare which would have resulted from a large-scale invasion have yet to be found. Therefore, we now like to think of the Postpalatial period at Knossos as one of a hybrid, between Cretan and Mainland cultures, likely created by a local elite who wished to maintain status in both spheres. As to who exactly these local elite were, we have some information. Those buried in warrior graves in the Postpalatial cemeteries around Knossos were born in the region, as recent analysis of skeletal materials has shown. The new Knossian elite did not come from the Mycenaean mainland.

Copyright: Dr. Senta German, “Knossos,” in Smarthistory, September 19, 2020, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/knossos/.

Mycenean Citadel

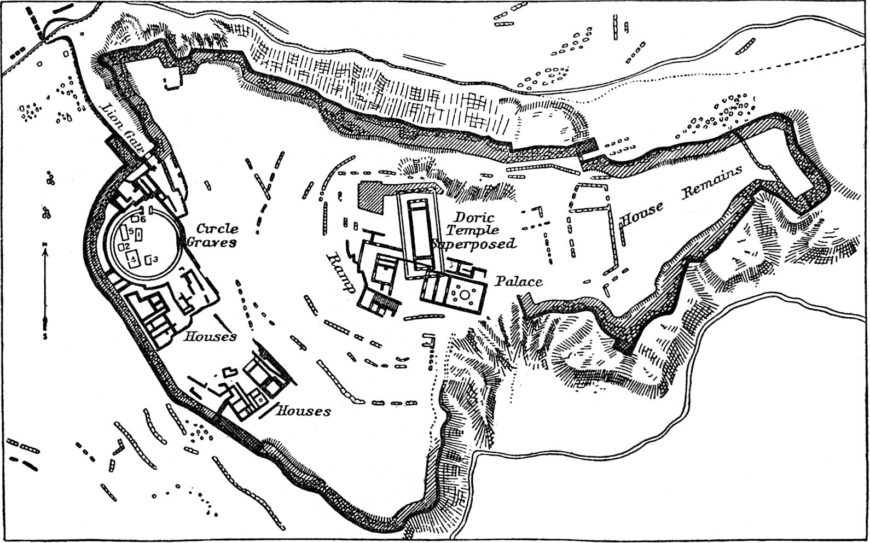

The ancient citadel (fortified city) at Mycenae is located on top of an isolated hill and provides truly spectacular views of the surrounding area, making it an ideal location for a defensive stronghold. Mycenaean culture dominated southern Greece, but is perhaps best known for the site of Mycenae itself, which includes the citadel (with a palace), and is surrounded by different forms of tombs and other structures. Mycenaean culture firmly establishes itself in the late Bronze Age, specifically, around 1600 B.C.E.

At around 1600 B.C.E.—seemingly out of nowhere—the shaft graves at the site of Mycenae are built. These are two circular walled plots containing graves, built some 50 years apart, close to the fortification wall of the citadel. Archaeologists named these “Grave Circle A” and “Grave Circle B.” Grave Circle B is earlier than A (but A was discovered first) and contained some 14 shaft graves with 24 burials; Grave Circle A held 6 shaft graves with 19 burials. These burials contained men, women, and children who were related to one another, recent DNA analysis has shown.

The focus sites of this era are Mycenaean palaces which all have several aspects in common: a central megaron or throne room with a large hearth which is adjacent to an open court, commanding views of an agricultural plane, colorful and often figural wall painting, and associations with grand burial structures such as tholoi (beehive tombs). These types of sites can be found not only at Mycenae but also at Tiryns, Iolkos, Orchomenos, Gla, Pylos, Thebes, and on the acropolis at Athens.

Mycenaean architects and engineers embraced a massive scale with huge hydraulic projects, far-flung road works, and defensive walls so gigantic they never succumb to burial, remaining largely intact and providing the inspiration for mythological explication until the modern era.

Around 1200 B.C.E. nearly all major Mycenaean sites experienced massive destruction, the cause of which is unclear. Many sites were quickly reinhabited, but the elite areas, such as the spaces where it is believed the Wanax ruled, were not rebuilt. For the next 50 to 75 years, pottery production and even wall painting continues but becomes less fine and increasingly regional, eventually ceasing all together. Burial practice changes as well, from shaft graves to small individual cist graves (small below-ground stone boxes) containing cremated remains.

By 1050 B.C.E., at the end of the Bronze Age, the Greek world (the Cycladic islands, Crete, and the Mainland), have only memories left of the once wealthy and far reaching polities which had ruled for nearly a millennium, an era soon to be beautifully enshrined in the oral epic tradition of Homer.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/tu5mKn3_h7Y?si=wk6HHpT5QrCNSCGj

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Cc9cLmgXp_A?si=FnQuXWVjQKfzIu6E

Copyright: Dr. Senta German, “Mycenaean art, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 25, 2020, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/intro-mycenaean-art/.

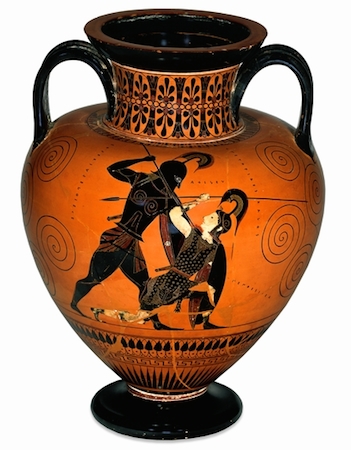

Greek Pottery

One of the most heavily traded artistic commodities in the ancient Mediterranean was pottery. For example, the Etruscans (in central Italy) were enthusiastic collectors of Athenian pottery in the sixth and fifth centuries, and many of the best-preserved pots, such as The Francois Vase, were found in Etruscan tombs.

While today Greek vases are housed in museums behind glass as fine art, in the ancient period, pots were primarily functional art, intended to be used rather than simply displayed. They were also cheaper than many other forms of art, like statuary, and were therefore available to a wider audience. They varied greatly in quality from plain ware with no painted decoration to large pots with elaborately painted scenes. Pots were thrown on a potter’s wheel, decorated with clay slip as paint, and fired in kilns.

In the eighth century in Athens, these everyday objects were monumentalized and used as grave markers. Pots like the Dipylon Amphora were large versions of smaller pots and decorated with geometric designs and funerary scenes, relating to their function.

In the seventh century, the city of Corinth became the center of pottery production in the Greek world, producing large numbers of vases with designs influenced by Near Eastern Art, such as the Macmillan Aryballos and pots in the so-called animal style. Many of these pots were mass produced for a wide market and feature repetitive designs. Corinth was a port city, and they set their pots out on the trading vessels that regularly moved through their harbors. Corinthian pots have been found at archaeological sites across the Mediterranean.

Attic pottery

In the sixth century, Athenian (or Attic) pottery eclipsed Corinthian pottery in popularity and a booming pottery industry developed in Athens. Potters and painters, who were usually separate people, began signing their higher quality artworks. Some of these signatures are from artists who came from across the Mediterranean to work in Athens. Artists were organized into workshops, which were usually owned by a potter, who employed painters and other workmen.

Potting was the more highly valued skill, as these vases were, above all, intended to be functional, and potters signed their work more frequently than painters. These signatures became similar to modern brand names, providing prestige for their owners, and there was competition between artists to be seen as the best at their craft. For example, the painter Euthymides signs one pot, “As never Euphronios (a fellow painter) could do.”

These Attic pots were painted with various subjects, including most commonly mythological and genre scenes, such as images of drinking parties, boys going to school, and women collecting water. While in the early and mid-sixth century, most of the painters, like Exekias, were using the black-figure technique to decorate their pots, the red-figure technique was invented towards the end of the sixth century in Athens, becoming the more popular style over the next few hundred years across the Greek world.

Developments in style in the fifth century towards more naturalistic and varied poses on pots like the Niobid Krater were primarily done in the red-figure style.

Copyright: Dr. Amanda Herring, “Pottery, the body, and the gods in ancient Greece, c. 800–490 B.C.E.,” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, July 21, 2022,

Greek Sculpture

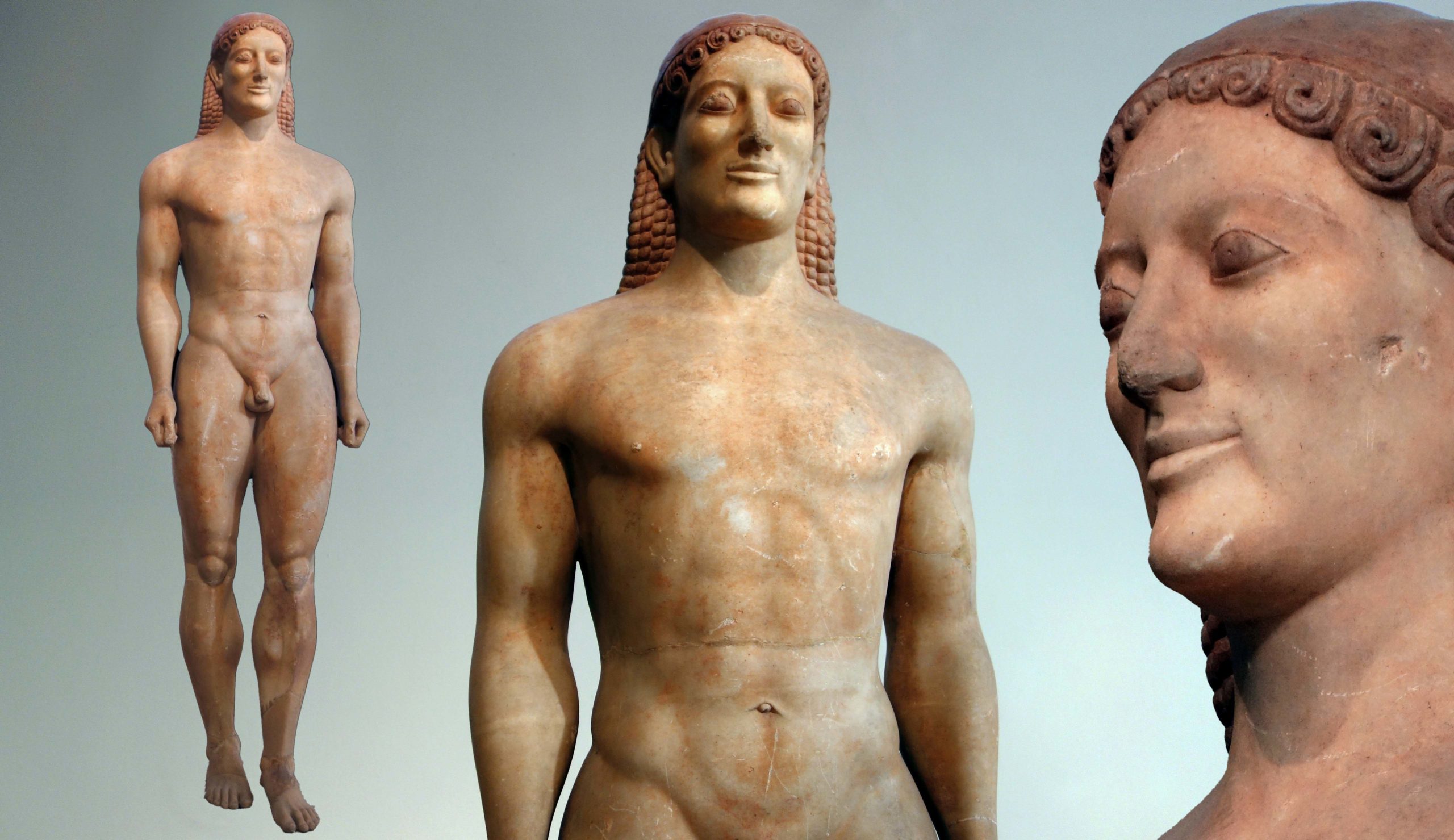

One of the most common types of dedications in sanctuaries, both panhellenic and civic, were statues. Statues were commissioned by both states and private individuals for a number of different purposes. Many were votive dedications given to the gods as a form of worship, while other sculptures commemorated athletic or military victories or celebrated an individual and their accomplishments, such as in grave markers. Still other statues, including small, relatively inexpensive terracotta statues, served as decorations in homes.

Most of the statues seen in public spaces such as sanctuaries were made of either bronze or white marble quarried on the Greek islands or mainland. All of these statues were originally painted in bright colors, both their skin and clothing, and painted designs were frequently included on the sculpted fabric. Even the bronze statues were colorful, with different types of alloys or surface treatments used to distinguish between the color of hair, skin, eyes, and clothing.

Humans were the most popular subjects of Greek statuary, and Greek artists were greatly concerned with the representation of the human body, especially the male nude. Gods, heroes, and Greek citizens were regularly depicted in the nude in Greek art, while non-Greeks were not. Goddesses and Greek women were commonly clothed in this period except when the lack of clothes indicated their vulnerability, such as victims of sexual assault, or their lower status, notably as prostitutes. Men practiced limited public nudity, notably in athletics, in their daily lives, but men in Greek art are regularly depicted in the nude in circumstances, such as warfare, when they would, in fact, have been clothed in real life. The male body therefore communicated symbolic messages about perceived Greek masculine virtues and heroic status. The male nude became an identifier for Greek men, separating them from women and barbarians.

For Greeks, the highly regarded virtue of self-control over mind, body, and emotions was expressed in an idealized, beautiful body. In addition, it also reflected ideas about the beauty of the young male body and Greek sexuality. Most Greek men had sexual relationships with both men and women. These relationships were undertaken both with prostitutes and with fellow citizens. The most common sexual relationship between male citizens was between an older partner in his twenties and a younger partner in his teens, known as pederasty. These relationships had socially defined roles for each partner, with the older man acting as the pursuer and the youth as the beloved, more passive partner. They were public relationships and were seen as having sexual and emotional benefits for the participants, as well as benefits for society since the older partner helped guide the younger partner into adulthood as a contributing member of society with an established set of socially acceptable beliefs. The male nudes of archaic and classical art are not overtly sexualized, but they represent young men at an age when they were pursued by older men and viewed as at their most beautiful. Nude statues can be dated by their depiction of the male body, with an increasing emphasis on a naturalistic depiction of the nude body over the course of the seventh through sixth centuries.

Kouroi and korai

A comparison of kouroi (statues of young men) and korai (statues of young men), which were common votive dedications and grave markers in the sixth century, demonstrates the differences in how men and women were depicted differently in Greek art. The kouroi, like the Anavysos Kouros, depict an idealized, nude young man with aristocratic long, braided hair.

The korai, like Peplos Kore, depict young women in elaborate clothing that was originally brightly painted with elaborate designs and jewelry. Citizen women were expected to stay within the domestic sphere, caring for children and the home, and undertaking tasks such as weaving. In many Greek poleis, such as Athens, a Greek woman had a male guardian, usually her father or husband, her entire life, as women were not believed to be able to impose self-control and manage their own affairs or participate in government or civic life except for religious events. The kore reflects the ideal Greek woman, a symbol of beautiful fertility, overseeing a prosperous household as demonstrated by her elaborate adornment.

The ancient Greeks mastered the naturalistic representation of the human body, and the Renaissance revived it.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/5vK7Z2Odnc0?si=6uARcLMFHo1QDtVg

Copyright: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Contrapposto explained,” in Smarthistory, December 16, 2015, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/contrapposto/.

For the ancient Greeks, the human body was perfect. Explore this example of the mathematical source of ideal beauty.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/zojMBDSiNIU?si=zlED6RyNo5QOBVAG

Copyright: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer),” in Smarthistory, April 27, 2023, accessed April 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/polykleitos-doryphoros-spear-bearer/.

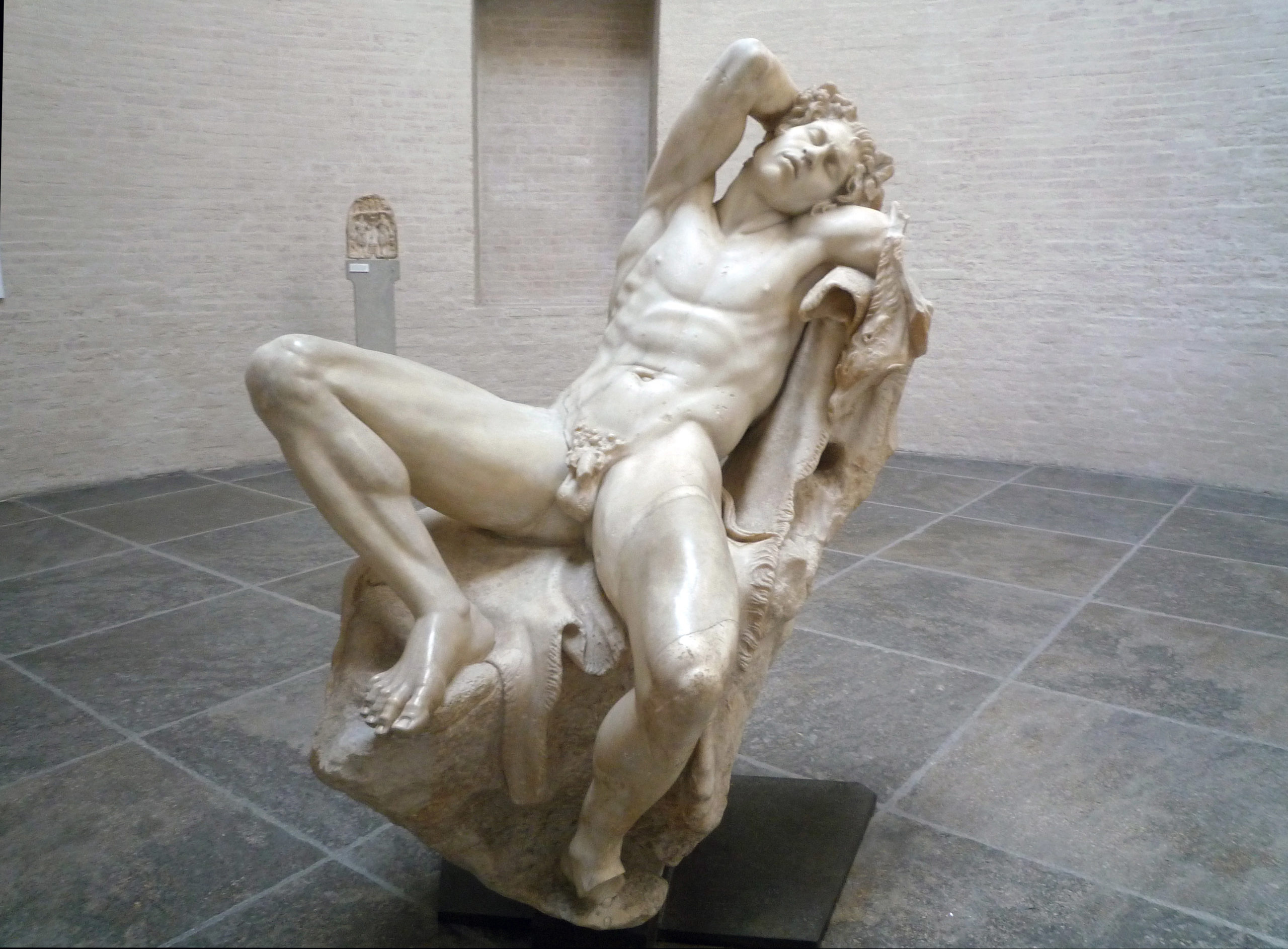

Hellenistic Sculpture

There is a large variation in what we identify as Hellenistic art, across the Hellenistic world and across the three centuries that we identify as the Hellenistic period. Yet, the Hellenistic world was intensely interconnected, with artistic ideas, trade, and people moving across huge swaths of territory. There were common cultural touchstones that connected these different areas, notably the spread of the common Greek language, the worship of Greek gods, and Greek artistic style and iconography. Yet, these were regularly re-interpreted on a local level by different populations, and the formation of art and identity was a constant negotiation that happened primarily on a local level.

As part of their establishment and maintenance of power, most Hellenistic rulers practiced cultural imperialism, promoting Greek language, culture, and religion in territories that previously did not identify as Greek. The period is now known as the Hellenistic period due to this spread of Greek (Hellenic) culture. Yet, this was not simply the imposition of Greek culture across passive, conquered peoples. These kings ruled over millions of people of different ethnicities who spoke numerous languages and worshiped various gods. The cultures, religions, and art of the conquered people influenced those of the conquerors in turn.

Aided by a more interconneced economic and political world, elites commissioned luxury goods like mosaics and metal wares that they displayed in their homes as signs of status. At the rulership level, art was used to advertise military victories, promote royal propaganda, and create new identities for their kingdoms and their people. Statues like the Nike of Samothrace were erected in panhellenic sanctuaries as statements of military power.

Reflecting the changing societies and cultures that emerged in the Hellenistic period, sculpture moved away from the idealism of the Classical period, embracing a wider variety of subjects and styles. Some Hellenistic statues, like the Nike of Samothrace, are dramatic and theatrical and require the viewer to engage with them physically by moving to different vantage points to view the artworks in their entirety

Others, like the Seated Boxer, embrace realism. The boxer depicts, not a young, idealized athlete, but a beaten, middle-aged man, reflecting changes in the role of athletics in Hellenistic society and the growth of professional athletes. Yet, the Seated Boxer could depict a different version of victory. This could be not an image of defeat, but rather the veteran boxer, who even when he looks defeated, can stand back up and win a bout in the ring.

Other statues reflect on the contrast between power and vulnerability. Sleeping figures, like the Barberini Faun and the Eros Sleeping, became popular. The Eros statue shows the god, whose arrows of erotic love could fell even the most powerful god, as an adorable, sleeping toddler.

The Barberini Faun depicts the physically large and muscled form of a satyr, a part animal, part human creature, asleep and distinctly vulnerable. He is also overtly sexualized in a way that earlier male nudes, and even most Hellenistic male nudes, were not. This new depiction of the male form reflects changes in ideas of sexuality in the Hellenistic period. While sexual relationships between two men were common in the earlier periods (see earlier chapter), the roles that each lover played were strictly and socially defined, as the relationships were seen to benefit society. In the Hellenistic period, there were changes in how people saw themselves within society, and where they looked for happiness and identity. As citizens of large kingdoms, rather than small city-states, people were more connected to the rest of the world through trade and political networks, and those that lived in large, cosmopolitan cities regularly came into contact with people of different ethnicities and cultures. Yet, many felt disconnected from their distant monarchical rulers, and often did not feel a common identity with their closest neighbors. People now frequently looked to family and personal relationships for happiness and identity, rather than their place within a civic structure. Sexual relationships were seen as one way to pursue happiness, resulting in a subsequent relaxing in the strict definitions of sexual roles. The Barberini Faun is illustrative of this change, as a mature man could now be seen as an object of desire.

Copyright: Dr. Amanda Herring, “Empire and Art in the Hellenistic world (c. 350–31 B.C.E.),” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, August 25, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/empire-art-hellenistic-world/.