1.2 Eastern Asia

Brief History of Cultures of East Asia

Imperial Chinese history is marked by the rise and fall of many dynasties and occasional periods of disunity, but overall the age was remarkably stable and marked by a sophisticated governing system that included the concept of a meritocracy. Each dynasty had its own distinct characteristics and in many eras encounters with foreign cultural and political influences through territorial expansion and waves of immigration also brought new stimulus to China. China had a highly literate society that greatly valued poetry and brush-written calligraphy, which, along with painting, were called the Three Perfections, reflecting the esteemed position of the arts in Chinese life. Imperial China produced many technological advancements that have enriched the world, including paper and porcelain.

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is characterized by the beginning of a settled human lifestyle. People learned to cultivate plants and domesticate animals for food, rather than rely solely on hunting and gathering. That coincided with the use of more sophisticated stone tools, which were useful for farming and animal herding. In China, this period began around 7000 B.C.E. and lasted until 1700 B.C.E.

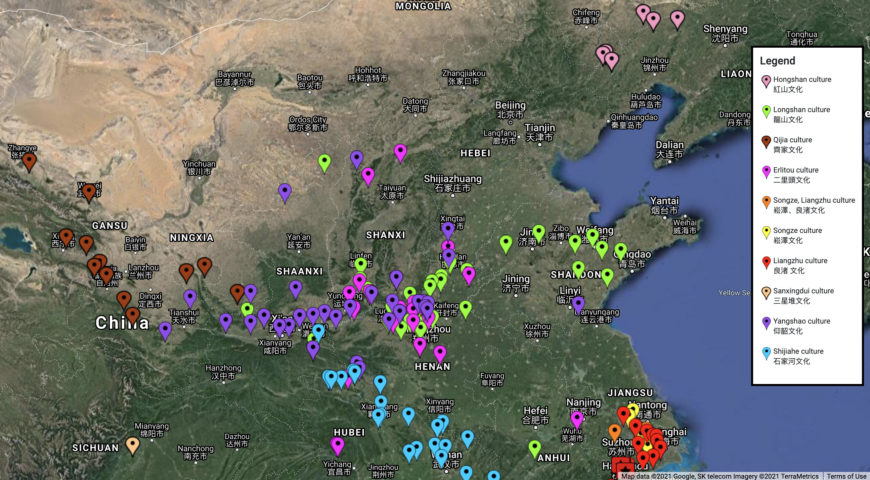

It is traditionally believed that Chinese civilization first emerged along the Yellow River and then spread to other parts of China. However, recent archaeological evidence suggests that a number of distinct cultures developed simultaneously across China, all along waterways. These cultures were located near the coastal areas, the Yellow River in the north, and the Yangzi River in the south. They are usually named after the site where remains of the culture were first discovered by modern archaeologists.

Neolithic people did not write. However, because they lived in settled communities, they left many traces behind, including the foundations of their houses, burial sites, tools, and crafts. We learn from the archaeological record that their diet included millet or rice, they domesticated pigs and dogs, and, as in all Neolithic cultures, there was extensive pottery production. Cultures in central China along the Yellow River were known for their painted pottery. Toward the late Neolithic period (c. 5000–1700 B.C.E.), fine gray and black pottery of elaborate forms were produced by cultures along the east and southeast coasts. The forms and decorative patterns of these pottery vessels continued to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 B.C.E.) and inspired the craftsmen of bronzes.

Jade carving is another advanced craft invented by Neolithic people. It plays a major part in Chinese culture to this day. Neolithic jade objects include personal ornaments, such as bracelets, earrings, and pendants, but most importantly, objects designed for ritual or ceremonial use, such as axe heads, blades, and knives. Hongshan culture (c. 3800–2700 B.C.E.) in the northeast produced some of the earliest jades used as pendants, including the so-called pig dragons (a creature with the head of a pig and the curled body of a dragon) and the toothed pendants (such as the pendant in the form of a mask, discussed in more detail below). [1] Both kinds were found placed on the chest of tomb occupants.

Status objects like elaborate pottery and carved jades were placed in tombs during the Neolithic period. This practice suggests two things: Neolithic people’s belief in the afterlife and the emergence of social classes. Only important and wealthy individuals had the privilege of being buried with these precious objects, especially jades. These objects were luxuries, not necessary for life but cherished for their beauty and ceremonial value. They required large amounts of raw materials and skilled labor to produce and were therefore accessible only to the ruling class, thus showing the existence of a surplus of wealth and labor in society.

The arts of Neolithic China not only demonstrate technical sophistication and superb craftsmanship but also reveal social organization and the emergence of religious beliefs.

Jōmon period (c. 10,500 – c. 300 B.C.E.): grasping the world, creating a world in Neolithic Japan

The Jōmon period is Japan’s Neolithic period. People obtained food by gathering, fishing, and hunting and often migrated to cooler or warmer areas as a result of shifts in climate. In Japanese, jōmon means “cord pattern,” which refers to the technique of decorating Jōmon-period pottery.

As in most Neolithic cultures around the world, pots were made by hand. Vessels would be built from the bottom up from coils of wet clay, mixed with other materials such as mica and crushed shells. The pots were then smoothed both inside and out and decorated with geometric patterns. The decoration was achieved by pressing cords on the malleable surface of the still-moist clay body. Pots were left to dry completely before being fired at a low temperature (most likely, just reaching 900 degrees Celsius) in an outdoor fire pit.

Later in the Jōmon period, vessels presented ever more complex decoration, made through shallow incisions into the wet clay, and were even colored with natural pigments. Jōmon-period cord-marked pottery illustrates the remarkable skill and aesthetic sense of the people who produced them, as well as stylistic diversity wares the different wages.

Also, from the Jōmon period, clay figurines have been found that are known in Japanese as dogū. These typically represent female figures with exaggerated features such as wide or goggled eyes, tiny waists, protruding hips, and sometimes large abdomens suggestive of pregnancy. They are unique to this period, as their production ceased by the 3rd century B.C.E. Their strong association with fertility and mysterious markings “tattooed” onto their clay bodies suggest their potential use in spiritual rituals, perhaps as effigies or images of goddesses. Besides dogū, this period also saw the production of phallic stone objects, which may have been a part of the same fertility rituals and beliefs.

Images of the female body as symbols of fertility were encountered in many parts of the world in the Neolithic period, presenting features unique to the regions and cultures that produced them. The preoccupation with fertility was increasingly twofold, namely the fertility of women and that of the land, as people began cultivating it and transitioning to a settled agricultural society.

Yayoi period (300 B.C.E. – 300 C.E.): influential importations from the Asian continent (I)

People from the Asian continent who were cultivating crops migrated to the Japanese islands. Archaeological evidence suggests that these people gradually absorbed the Jōmon hunter-gatherer population and laid the foundation for a society that cultivated rice in paddy fields, produced bronze and iron tools, and was organized according to a hierarchical social structure. The Yayoi period’s name comes from a neighborhood of Tokyo, Japan’s capital, where artifacts from the period were first discovered.

Yayoi-period artifacts include ceramics that are stylistically very different from the cord-marked Jōmon-period ceramics. Although the same techniques were used, Yayoi pottery has sharper and cleaner shapes and surfaces, including smooth walls, sometimes covered in slip, and bases on which the pots could stand without being suspended by a rope. Burnished surfaces, finer incisions, and sturdy constructions that suggest an interest in symmetry are characteristic of Yayoi pots.

Some studies suggest that Yayoi pottery is linked to Korean pottery of the time. The Korean influence extends beyond ceramics and can be seen in Yayoi metalwork as well. Notably, Yayoi period clapper-less bronze bells closely resemble much smaller Korean bells that were used to adorn domesticated animals such as horses.

These bells, together with bronze mirrors and occasionally weapons, were buried on hilltops. This practice was seemingly linked to ritual and may have been considered auspicious, perhaps for the fertility of the land in this primarily agricultural society. The magical or ritualistic function of the bells is further suggested by the fact that the bells were not only clapper-less, but also had walls that were too thin to ring when hit.

The bells became larger later in the Yayoi period, and it is believed that the function of these larger bells was ornamental. Across regions and over the span of a few centuries, such bells varied in size from approximately 10 cm to over 1 meter in height.

Dr. Sonia Coman, “Jōmon period, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, January 20, 2021, accessed April 9, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/jomon-period/.

Dr. Sonia Coman, “Yayoi period, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, January 20, 2021, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/yayoi-period/.

Confucianism

Life of Confucius

It was whilst he was teaching in his school that Confucius started to write. Two collections of poetry were the BOOK OF ODES (Shijing or Shi King) and the BOOK OF DOCUMENTS (Shujing or Shu King). The SPRING AND AUTUMN ANNALS (Lin Jing or Lin King), which told the history of Lu, and the BOOK OF CHANGES (Yi Jing or Yi King) was a collection of treatises on divination.

Unfortunately for posterity, none of these works outlined Confucius’ philosophy. Confucianism, therefore, had to be created from second-hand accounts and the most reliable documentation of the ideas of Confucius is considered to be the Analects, although even here there is no absolute evidence that the sayings and short stories were actually said by him and often the lack of context and clarity leaves many of his teachings open to individual interpretation.

It was whilst he was teaching in his school that Confucius started to write. Two collections of poetry were the BOOK OF ODES (Shijing or Shi King) and the BOOK OF DOCUMENTS (Shujing or Shu King). The SPRING AND AUTUMN ANNALS (Lin Jing or Lin King), which told the history of Lu, and the BOOK OF CHANGES (Yi Jing or Yi King) was a collection of treatises on divination.

Unfortunately for posterity, none of these works outlined Confucius’ philosophy. Confucianism, therefore, had to be created from second-hand accounts and the most reliable documentation of the ideas of Confucius is considered to be the Analects, although even here there is no absolute evidence that the sayings and short stories were actually said by him and often the lack of context and clarity leaves many of his teachings open to individual interpretation.

Confucian Philosophy

Relationships

Relationships are important in Confucianism. Order begins with the family. Children are to respect their parents. A son ought to study his father’s wishes as long as the father lives; and after the father is dead, he should study his life, and respect his memory (Confucius 102).

A person needs to respect the position that s/he has in all relationships. Due honor must be given to those people above and below oneself. This makes for good social order. The respect is typified through the idea of Li. Li is the term used to describe Chinese proprietary rites and good manners. These include ritual, etiquette, and other facets that support good social order. The belief is that when Li is observed, everything runs smoothly and is in its right place.

Relationships are important for a healthy social order and harmony. The relationships in Li are

- Father over son

- Older brother over younger

- Husband over wife

- Ruler over subject

- A friend is equal to a Friend

Each of these relationships is important for balance in a person’s life. There are five main relationship principles: Hsiao, Chung, yi, xin, and Jen.

- Hsiao is love within the family. Examples include the love of parents for their children and of children for their parents. Respect in the family is demonstrated through Li and Hsiao.

- Chung is loyal to the state. This element is closely tied to the five relationships of Li. Chung is also basic to the Confucian political philosophy. An important note is that Confucius thought that the political institutions of his day were broken. He attributed this to unworthy people being in positions of power. He believed rulers were expected to learn self-discipline and lead through example.

- Yi is righteousness or duty in an ordered society. It is an element of social relationships in Confucianism. Yi can be thought of as internalized Li.

- Xin is honesty and trustworthy. It is part of the Confucian social philosophy. Confucius believed that people were responsible for their actions and treatment of other people. Jen and Xin are closely connected.

- Jen is benevolent and humaneness towards others. It is the highest Confucian virtue and can also be translated as love. This is the goal for which individuals should strive.

Confucian Rituals

Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

Art of the Line

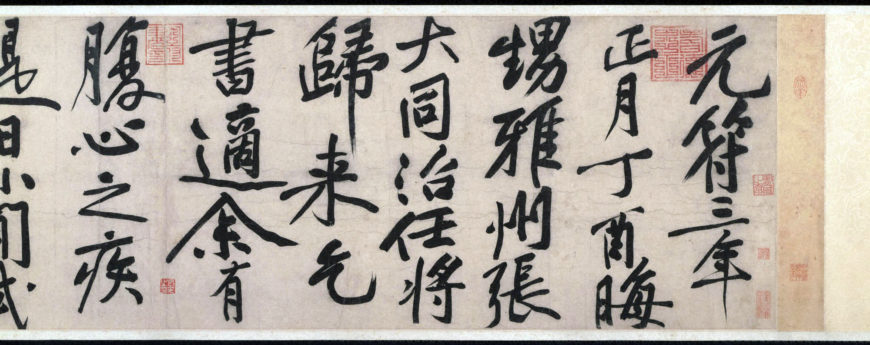

Calligraphy is the world’s oldest abstract art—the art of the line. This basic visual element can also hold a symbolic charge. Nowhere has the symbolic power of the line manifested itself more fully than in Chinese calligraphy, a tradition that spans over 3,000 years. The aesthetics of calligraphy are important to the history of art in East Asia, where during much of its premodern era classical Chinese was the lingua franca (or common language).

Knowing how to read and write Chinese characters is not a prerequisite for appreciating the unique charm of calligraphy. The characters are fundamentally ideographic in nature, meaning they can symbolize the idea of a thing rather than transcribe its pronunciation. A calligrapher wields a pliant brush, dips its tip fashioned with animal hair into ink made from grinding on an ink stone with water, and writes on paper or silk that could have different absorbency rates depending on how it has been treated. Brush, ink, ink stone, and paper are collectively referred to as the “Four Treasures of the Study” 文房四寶.

A capable calligrapher can achieve a surprisingly wide and rich array of artistic effects that eloquently convey the personality of the artist and the ambiance of the moment of inspiration. The responsiveness of the pliant brush lends itself to registering the subtle changes in pressure, direction, and speed in the force transmitted from the shoulder of the calligrapher, to his arm, wrist, and finally fingertips. This accounts for calligraphic brushstrokes’ unique facility in capturing with great vividness and immediacy the kinetic energy that coursed through the calligrapher’s body during the creation process.

The vocabulary of calligraphy

There are five major script types used today in China. In the general order of their appearance, there are: seal script, clerical script, cursive script, running script, and standard script. Each script type has its own defining visual traits and lends itself to different kinds of textual content and function. Being able to recognize these five script types constitutes the first step in understanding Chinese calligraphy and its nuanced visual vocabulary. As the calligrapher chooses the script type that best suits the occasion of writing and his mood, being able to discern the differences between these types amounts to possessing the key to deciphering the calligrapher’s mind at the moment of creation. An additional reason is that calligraphies had been historically categorized by script type rather than by the content of the text, a fact that highlights the primacy of the visual form in the critical conversations associated with this art.

It is also possible to have more than one script type in the same work of art, usually in the form of colophons (on handscrolls) or inscriptions (on hanging scrolls), as the calligrapher who appended his comments to the original work felt compelled to use a particular type of script.

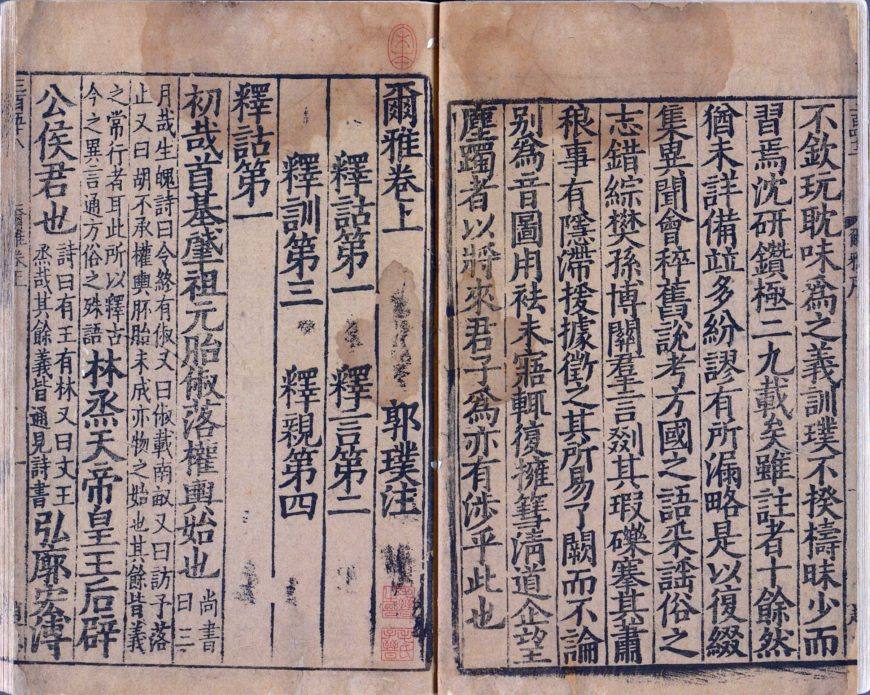

Seal script—the first script type to emerge in this sequence—was solidified during the Qin dynasty (221–207 B.C.E.). The seal script signified authority, permanence, and orthodoxy, qualities befitting of the first imperial dynasty that unified China and standardized the writing system. Arranged in orderly columns, each character fits in an imaginary square. The strokes are of relatively even thickness, and the speed of execution is steady and slow. The solemnity of the seal script made it (and still makes it) a popular choice for commemorative titles carved onto the head of stone steles for public display or in frontispieces that announce the title of a handscroll painting. Even though this script type was most associated with the short-lived Qin dynasty, it served as the script of choice for titles of artworks such as a 10th-century masterpiece, called The Night Revels of Han Xizai, that documented a sumptuous party at a court minister’s house.

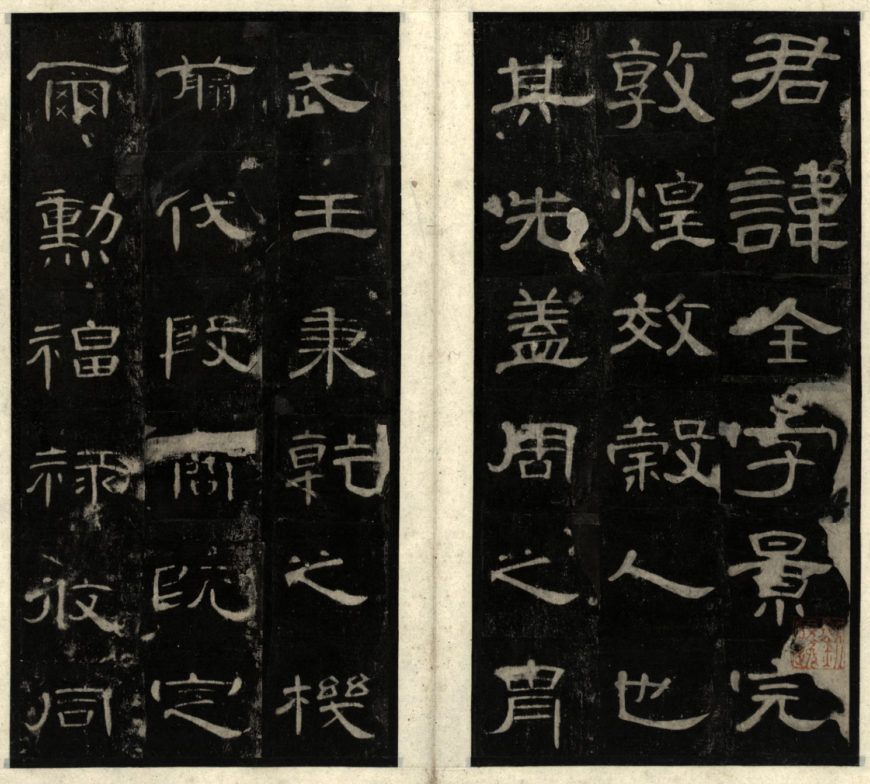

Clerical script reached its height in the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 C.E.). The character in general has a squatter silhouette when compared to its predecessor the seal script, introducing the possibility for greater rhythm in the composition. The strokes start displaying modulations and inflections (note the elegant flaring brush movement in the horizontal strokes), reflective of the different amounts of pressure in the brush. This marks the calligrapher’s conscious exploration of the brush’s expressive potential. Clerical script takes less time to write than seal script, and it likely emerged out of a need for more efficient record-keeping demanded by an expanding empire (the territory of the Han dynasty was much larger than that under the Qin). The name for the script also suggests that it was initially used by government clerks. The clerical script is popular for commemorative texts carved into stone steles, such as we see on the Cao Quan stele.

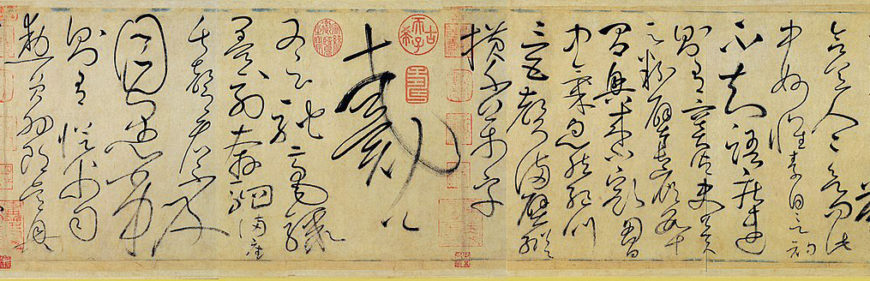

Cursive script is the most expressive of all five script types; it affords a calligrapher remarkable freedom thanks to this script’s relaxation of the orthographic constraints of the seal and clerical scripts. Essentially an informal shorthand of the more complex forms of characters, cursive script was widely seen in epistolary writing (correspondence by letter), due to the expedient nature of its execution. Because the characters are more simplified, more freedom is allowed on the calligrapher’s part to improvise and to take more liberty with the shape of the character. Since its maturation in the 4th century, the cursive script has been the choice for many master calligraphers to demonstrate their individuality. Calligraphy done in cursive script readily reveals the speed at which each character was brushed, sometimes so fast that two or more characters are interconnected by ligatures (the fusion of the final stroke of the first character into the first stroke of the second). Some of the most renowned cursive calligraphers were Buddhist monks who often were most inspired in a state of inebriation. Historically, some of the most famous cursive calligraphers were Chan monks, as the expressivity of the cursive script lends itself well to the unrestricted spirit associated with Chan Buddhists. Buddhist monasteries were important centers of learning in premodern China.

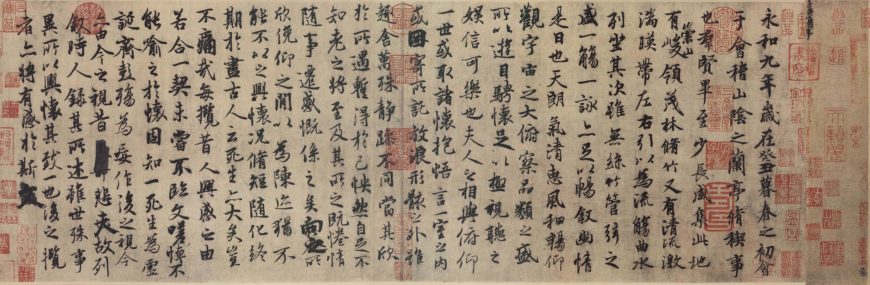

The running script combines the legibility of the standard script and the expressivity of the cursive script. The Song dynasty (960–1279 C.E.) with its literati calligraphers (scholar-officials who obtained government posts after passing the civil service examination) saw a flowering of calligraphy in running script. This script became the preferred one for the greatest Song calligraphers because it lends itself to the trend at the time towards more personal—even idiosyncratic—styles. Calligraphy in this script type allows a wide range of speed in the execution of the strokes and gives the calligrapher an opportunity to demonstrate familiarity with great calligraphers of the past. The Chinese calligrapher derives artistic legitimacy by demonstrating mastery of a repertoire of calligraphic styles that constitute the canon of Chinese calligraphy.

Standard script—the script type that most learners of Mandarin today encounter first during their studies—appeared the latest in the evolutionary sequence of Chinese calligraphy. Standard script reached its zenith during the Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.) and it is associated with the moral uprightness of the calligrapher, due to its emphasis on the balance around a central axis in its form. It is the ubiquitous script for almost all kinds of printed media in the Chinese language, because it is the most legible of all five script types. Each character can be assembled using a standardized repertoire of brushstrokes that consist mainly of orthogonal (at right angles) strokes, making it fairly easy to reproduce texts in this script type using woodblock printing technology. The world’s earliest extant example of this technology was printed in China in the 7th century, and later during the 11th century (in the Northern Song dynasty) movable-type printing was invented. It is fair to say that the standard script made a unique contribution to the dissemination of knowledge in premodern East Asia.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/MEN0CzGv5-Y?si=ll_DZkLXSCjG8Uf7

Copyright: Dr. Xiaohan Du, “Chinese calligraphy, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, September 15, 2020, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/chinese-calligraphy-intro/