13 Phonotactics

In oder to provide a concise introduction to phonology, we are going to concentrate on syllables and their structure. A syllable is a speech unit that is used to organize how we speak. Speech can usually be divided up into a whole number of syllables: for example, the word concern is made of two syllables: con and cern.

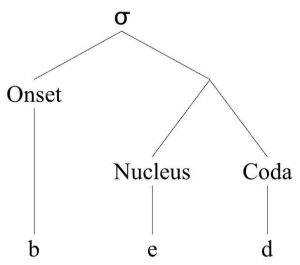

Syllables are usually made up of a nucleus which is usually a vowel (or a set of vowel sounds). And this nucleus can be preceded by an onset of composed of a consonant or a consonant cluster, and followed by a coda, which can also be composed of a consonant or a consonant cluster. For example, for the English word stress which is made up of only one syllable, the onset is composed of the sounds [s] and [t] and the coda is made up of just one sound [s]. For the English word criminal, which is composed of three syllables [ˈkrɪ-mɪ-nəl]. The first syllable has a coda made up of two sounds [k] and [r] but it has no coda. The second syllable’s onset is just one consonant [m] and it has no sound in its coda. And the final syllable has one consonant in the onset [n] and one in the coda [l].

Now the composition of syllables in different languages follows different rules or constraints, meaning that the way each language allows certain sounds to be present in certain positions within a syllable or within a word. Certain physical units cannot be used in some environments at all. Each language has its own set of phonotactics, which are language-specific restrictions on what combinations of physical units are allowed in which environments. For example, English has phonotactic restrictions that ban [tl] and [dl] in onsets, but this is not a universal restriction. Plenty of languages allow onsets with [tl] and [dl], such as Ngizim, which has words like [tlà] ‘cow’ (Schuh 1977), and Hebrew, which has words like [dli] ‘bucket’ (Klein 2020).

Some phonotactic restrictions may be somewhat looser than others. English generally does not have onsets containing [pw] or [vl], yet English speakers generally have no trouble pronouncing loanwords like pueblo [pwɛblo] and proper names like Vladimir [vlædəmir].

Lets see a simple example. In the case of Brazilian Portuguese, words cannot end in a final stop consonant. This means that there are no native Brazilian Portuguese words that end in the sounds [p t k b d g], this is, of course not the case of English, a language that allows for words to end with these sounds as in book, or dog.

A more complex example. This time in the English language. English usually allows for onsets of syllables of three consonants but only if the first consonant is the sibilant [s] followed by one voiceless stop [p t k], and followed by any of these four sounds [l ɹ j w]. Otherwise, only two consonants are allowed to take that position. This restriction allows the structure of words like strange [stɹeɪndʒ], or spleen [splin], but under these constraints, for an English speaker, a made up word like shkrom [ ʃkrom] would not sound English-like, while something like strum [strum] would. Because the first one does not obey this phonological constraint for English onsets and the second does.

Another example: Japanese tends to avoid consonant clusters so the preferred syllable structure is that of a consonant followed by a vowel, or a CV syllable (CV meaning a combination of a C=consonant + V= vowel). This means that syllables in Japanese can only have one consonant at the onset and none at the coda. Although it is possible to have a nasal as a coda in syllables, but not any other types of consonants. To update the rule for Japanese syllables, the true pattern is the following: CV(nasal). This pattern applies across the board to all syllables in Japanese words, which indicates that syllables in Japanese are made up of a simple (one sound) onset, the nucleus and, optionally, a nasal sound in a coda. And no other syllables are possible.

Now lets see how these how these constraints interact in language learning. Imagine a speaker of Brazilian Portuguese who is learning English. Remember that Brazilian Portuguese has a constraint that prohibits stop consonants to finish a word. So, when learning English, these speakers need to be able to process and produce these sounds whose positions are illegal in their native language. So once they hear something that is impossible for them to process (like the English word book because it ends in a stop consonant) they repair that word as if it was defective (because it is defective if they use the restriction available in their native Portuguese phonology) and they hear and produce a vowel sound after the final stop to make it phonotactically legal to their native phonological restriction. In the case of Brazilian Portuguese speakers, they insert vowel [i].

So English a word like book [bʊk] is heard and produced as [bʊki] and a word like bag [bæɡ] are heard and produced as [bæɡi].

So, you can see that phonology and phonotactic constraints are used as filters when listening to foreign and second language speech that does not follow these constraints. Our native language’s constraints allow us to reprocess certain sounds to conform to the mental structure we have for our own language or languages.

Now let s see another example. Lets go back to Japanese. Remember that Japanese only allows for CV syllables or CV plus a nasal. This means that syllables can only be composed of one consonant followed by a vowel and optionally followed by a nasal sound. So when presented with English words, Japanese speakers hear and produce the following words.

The English word stop [stɒp] is produced as [sɯtɒpɯ]

The English word trash [træʃ] is produced as [toræʃɯ]

The English word fantastic [fæntæstɪk]is produced as [fæntæsɯtɪkɯ]

In the case of Japanese, the input they hear is reconstructed and vowels are inserted to comply with Japanese constraints. More concretely, in cases where there is no vowel after one of the consonants, the vowel [o] is inserted after [t] and [d], while the high back unrounded vowel [ɯ] is inserted after all other consonants. So an English syllable like [kris] is pronounced as [kɯrisɯ] and [drɪl] is pronounced as [dorɪlɯ].

Of course, the examples provided here are not faithful representations of how native Japanese speakers with no training in English pronounce this words. These are representations of how they would pronounce them if they only applied the syllabic constraint of their native phonology, but we know that they may pronounce some consonant and vowel sounds different. But for now, we are going to concentrate on how the structure of the syllables change. We will not consider any other changes. So for the assignment activity, lets assume that Japanese speakers can use all consonants and vowels available in English, just make sure you focus on how the structure of the word is affected by these syllabic changes.

Adapted from:

Anderson, C., Bjorkman, B., Denis, D., Doner, J., Grant, M., Sanders, N. & Taniguchi, A. (2022). Essentials of Linguistics. Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics2/