10 Describing Consonants: Place of Articulation

Describing consonants: Place of articulation

Consonants as constrictions

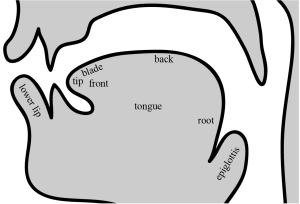

Consonants are phones that are created with relatively narrow constrictions somewhere in the vocal tract. These constrictions are usually made by moving at least one part of the vocal tract towards another, so that they are touching or very close together. The moving part is called the active or lower articulator, and its target is called the passive or upper articulator. Vowels have wider openings than consonants, so they are not usually described with the terms used here.

Active articulators

- the lower lip, which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words pin and fin

- the tongue tip (the frontest part of the tongue; also called the apex), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words tin and sin

- the tongue blade (the region just behind the tongue tip; also called the lamina), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words thin and chin

- the tongue front (the tip and blade together as a unit, also called the corona); it is useful to have a unified term for the tip and blade together, since they are so small and so close, and languages, and even individual speakers of the same language, may vary in which articulator is used for similar phones; for example, while many English speakers use the tongue tip for the consonant at the beginning of the word tin, other speakers may use the tongue blade or even the entire tongue front; however, while there may be variation in some languages, the distinction between the tip and blade is crucial in others, such as Basque (a language isolate spoken in Spain and France), which distinguishes the words su ‘fire’ and zu ‘you’, both of which sound roughly like the English word sue, with the tongue tip used for su and the tongue blade used for zu (although this distinction has been lost for some speakers under influence from Spanish; Hualde 2010)

- the tongue back (the upper portion of the tongue, excluding the front; also called the dorsum), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words kin and gone

- the tongue root (the lower portion of the tongue in the pharynx; also called the radix), which is not used for consonants in English but is used for consonants in some languages, such as Nuu-chah-nulth (a.k.a. Nootka, an endangered language of the Wakashan family, spoken in British Columbia; Kim 2003)

- the epiglottis (the large flap at the bottom of the pharynx that can cover the trachea to block food from entering the lungs, forcing it to go into the esophagus instead), which is not used for consonants in English but is used in for consonants in some languages, such as Alutor (a Chukotkan language of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan, spoken in Russia; Sylak-Glassman 2014)

Note that while the lower teeth could theoretically be an active articulator (we can move them towards the upper lip, for example), it turns out that no known spoken language uses them for this purpose, so we do not include them here.

Each of the active articulators has a corresponding adjective to describe phones with that active articulator. These adjectives are given in the list below, again from front to back:

- labial (articulated with the lower lip)

- apical (articulated with the tongue tip)

- laminal (articulated with the tongue blade)

- coronal (articulated with the tongue front)

- dorsal (articulated with the tongue back)

- radical (articulated with the tongue root)

- epiglottal (articulated with the epiglottis)

Thus, we could say that the English words pin and fin begin with labial consonants, while thin and chin begin with laminal consonants. Note that all apical and laminal consonants are also coronal, so thin and chin can also be said to begin with coronal consonants.

Passive articulators

The passive articulators we find in phones across the world’s spoken languages are listed below, in order from front to back. the upper lip, which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words pin and bin

- the upper teeth, which are used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words fin and thin

- the alveolar ridge (the firm part of the gums that extends just behind the upper teeth, recognizable as the part of the mouth that often gets burned from eating hot food), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words tin and sin (though some speakers may use the upper teeth instead or in addition)

- the postalveolar region (the back wall of the alveolar ridge), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words shin and chin

- the hard palate (the hard part of the roof of the mouth; sometimes called the palate for short), which is used for the consonant at the beginning of the English word yawn

- the velum (the softer part of the roof of the mouth; also called the soft palate), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words kin and gone

- the uvula (the fleshy blob that hangs down from the velum), which is not used for consonants in English but is used for consonants in some languages, such as Uspanteko (an endangered Greater Quichean language of the Mayan family, spoken in Guatemala; Bennett et al. 2022)

- the pharyngeal wall (the back wall of the pharynx), which is not used for consonants in English but is used in languages that have consonants with the tongue root or epiglottis as an active articulator (such as Nuu-chah-nulth and Archi mentioned earlier)

Each of the passive articulators has a corresponding adjective to describe phones with that passive articulator. These adjectives are given in the list below, again from front to back:

- labial (articulated at the upper lip)

- dental (articulated at the upper teeth)

- alveolar (articulated at the alveolar ridge)

- postalveolar (articulated at the back wall of the alveolar ridge)

- palatal (articulated at the palate)

- velar (articulated at the velum)

- uvular (articulated at the uvula)

- pharyngeal (articulated at the pharyngeal wall)

Thus, we could say that the English words tin and sin begin with alveolar consonants, while kin and gone begin with velar consonants.

Since all consonants have two articulators, they could be described by either of the two relevant adjectives. For example, the consonant at the beginning of the English word shin could be described as a laminal consonant (because of its active articulator) as well as a postalveolar consonant (because of its passive articulator).

Note that the term labial is ambiguous in whether it refers to the lower or upper lip. In general, this ambiguity is not a problem, so labial consonants include those with the lower lip as an active articulator as well as those with the upper lip as a passive articulator.

Place of articulation

The overall combination of an active articulator and a passive articulator is called a consonant’s place of articulation, or simply place for short. Places of articulation are sometimes described with a compound adjective that refers to both articulators. There are eight locations that are important for the production of English sounds:

Consonants that use both lips as articulators, such as the consonants at the beginning of the English words mold, pin and bin, are called bilabial. Note that for bilabial phones, both lips are involved roughly equally, with each actively moving towards the other as mutual targets. There are four bilabial sounds in English [p] as in pat, [b] as in bat, [m] as in mat, and [w] as in with.

Next are labiodentals. Labiodental consonants are articulated with the lower lip against the upper front teeth. English has two labiodentals: [f] as in fall and [v] as in vote.

Interdental consonants are those produced in such a way that the tongue protrudes between the two sets of teeth, with the tongue blade below the bottom edge of the upper teeth. There are two interdental sounds in most varieties of American English: [θ] as in thigh and [ð] as in thy.

Alveolar sounds are made with the tongue tip at or near the front of the upper alveolar ridge. The alveolar ridges are the bony ridges of the upper and lower jaws that contain the sockets for the teeth. The front of the upper alveolar ridge, which is the most important area in terms of describing alveolar consonants, is the part you can feel protruding just behind your upper front teeth. From now on, any reference to the alveolar ridge means specifically the upper alveolar ridge. English has eight alveolar consonants: [t] tab, [d] dab, [s] sip, [z] zip, [n] noose, [ɾ] is the second flap sound in the word atom, [l] loose, and [ɹ] red.

Post-alveolar sounds are made a bit farther back. If you let your tongue or finger slide back along the roof of your mouth, you will find that the front portion is hard and the back portion is soft. Post-alveolar sounds are made with the front of the tongue just behind the alveolar ridge, right at the front of the hard palate and the body of the tongue closes up the airflow a bit as well, creating an obstruction further back than the alveolar ridge. English has four post-alveolar sounds: [ʃ] as the last consonant in leash, [ʒ] as the third sound in measure, [ʧ] as the first sound in church, and [ʤ] as the first sound in judge.

Palatal sounds are made with the body of the tongue near the center of the hard portion of the roof of the mouth (or the ‘hard palate’). English has only one palatal sound: [j] which is the first sound in the word yes.

Velar consonants are produced at the velum, also known as the soft palate, which is the soft part of the roof of the mouth behind the hard palate. Sounds made with the back part of the tongue body raised near the velum are said to be velar. There are three velar sounds in English: [k] as in kill, [ɡ] as in gill, and [ŋ] as the last sound in the word sing.

Finally, glottal sounds are produced when air is constricted at the larynx. The space between the vocal folds is the glottis. English has two sounds made at the glottis. One is easy to hear: [h], as in high and history. The other is called a glottal stop [ʔ] and this sound occurs before each of the vowel sounds in uh-oh or in the middle of a word like cotton.

Adapted from:

Anderson, C., Bjorkman, B., Denis, D., Doner, J., Grant, M., Sanders, N. & Taniguchi, A. (2022). Essentials of Linguistics. Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics2/