11 Describing Consonants: Manner of articulation

The third aspect of consonant description, in addition to voicing (whether a consonant is voiced or voiceless) and giving the consonant’s place of articulation, is its manner of articulation; that is, it is necessary to describe how the airstream is constricted or modified in the vocal tract to produce the sound. The manner of articulation of a consonant depends largely on the degree of closure of the articulators so how close together or far apart they are when the air comes through the mouth.

Stops (also known as plosives) are made by obstructing the airstream completely in the oral cavity. Notice that when you say [p] and [b], your lips are pressed together for a moment, stopping the airflow. Air pressure rises, and it is concentrated in the vocal tract. This concentration of air is then released as a burst of air.

Fricatives are made by forming a nearly complete obstruction of the vocal tract. The opening through which the air escapes is very small, and as a result a turbulent noise is produced. Such a turbulent, hissing mouth noise is called frication, hence the name of this class of speech sounds.

Affricates are complex sounds, made by briefly stopping the airstream completely and then releasing the articulators slightly so that frication noise is produced. They can thus be described as beginning with a stop and ending with a fricative, as reflected in the phonetic symbols used to represent them. English has only two affricates, [ʧ], as in church, and [ʤ], as in judge. [ʧ] is pronounced like a very quick combination of a [t], pronounced somewhat farther back in the mouth, followed by [ʃ]. It is a voiceless post-alveolar affricate. [ʤ] is a combination of [d] and [ʒ].

Nasals are produced by relaxing the velum and lowering it, thus opening the nasal passage to the vocal tract. In most speech sounds, the velum is raised against the back of the throat, blocking off the nasal cavity so that no air can escape through the nose. So when the velum is lowered and air escapes through the nasal cavity, like it happens with [m], as in rim, [n], as in kin, and [ŋ], as in king. For nasals there is a complete obstruction of the airflow in the oral cavity, but unlike stops, the air continues to flow freely through the nose. For [m], the obstruction is at the lips; for [n], the obstruction is formed by the tongue tip and sides pressing all around the alveolar ridge; and for [ŋ], the obstruction is caused by the back of the tongue body pressing up against the velum. In English, all nasals are voiced.

Liquids are formed with a severe constriction without fully stopping air from flowing. The first liquid we have in English is the alveolar lateral liquid [l]. In this sound, the front of the tongue is pressed against the alveolar ridge, but unlike in a stop, where the tongue is sealed all the way around the ridge, the sides of the tongue are relaxed letting the air flow freely over them. Liquids are usually voiced in English, so [l] is a voiced alveolar lateral liquid. The other liquid in English is [ɹ]. It involves curling the tip of the tongue back behind the alveolar ridge to make a retroflex sound.

Glides are made with only a slight closure of the articulators (so they are fairly close to vowel sounds), and they require some movement of the articulators during production. [w] is made by raising the back of the tongue toward the velum. [j] is made with a slight constriction in the palatal region using the front of the tongue.

The last manner of articulation is the flap. A flap which is sometimes called a tap, is similar to a stop in that it involves the complete obstruction of the oral cavity. The closure, however, is much faster than that of a stop: the articulators strike each other very quickly. In American English, we have an alveolar flap, in which the tip of the tongue is brought up and simply allowed to quickly strike the alveolar ridge before it moves into position for the next sound.

Putting it all together!

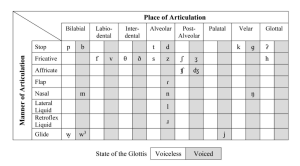

We now have three different ways to talk about how a consonant phone is articulated: its voicing, its place of articulation, and its manner of articulation. We can put these three together to give a complete description of the most common consonant phones. There are many consonants that go beyond this three-part description and require a bit more information to be fully specified, but for the purposes of this course, these three categories will be sufficient. You can find all the sounds of English categorized in the table below.

Adapted from:

Anderson, C., Bjorkman, B., Denis, D., Doner, J., Grant, M., Sanders, N. & Taniguchi, A. (2022). Essentials of Linguistics. Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics2/